We are now a month away from the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2024 between 26th and 28th April, so not quite on the countdown but certainly getting near to it after the imminent Easter vacation. Consequently, if you haven’t had a look at the programme to join us for a wide range of fascinating talks on a broad range of medieval topics, please do check out the website using either: https://ckhh.org.uk/mcw or https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury and we will be delighted to see you.

Among our fantastic speakers are those returning, such as Professor Mark Bailey, Dr Janina Ramirez, Dr David Rundle and Imogen Corrigan as well as new faces, including Dr Claire Martin, Professor Chris Woolgar, Dr Alexandra Lee and Alfred Hawkins; and, of course, it will be great to welcome back to Canterbury Professor Louise Wilkinson. Thus, we’ll be moving across the medieval landscape from some extraordinary women in the early Middle Ages to the Boleyn family by way of such fabulous topics as aspects of the First Crusade, Kent rebels, the Tower of London, plague in medieval Italy, London merchants, the late medieval household, the Green Man, craftsmanship in early Renaissance France and the Italian Renaissance. For all of these and more, do please see the CKHH website.

Now for this week, I am going to give a summary of the event at the Kent History & Library Centre at Maidstone yesterday (Monday) and then a brief report on the ‘Migrants, Merchants and Mariners in the Kentish Cinque Ports, c.1400-c.1600’ at Dover Museum last Saturday. Starting with Maidstone, Sarah Stanley and Dr Mark Bateson of the Kent Archives Service were hosting an event for the Cinque Ports Confederation to showcase individually and collectively the wonderful documents belonging to the Cinque Ports that are held at the county archives. The day began with mayors, barons, common clerks, town sergeants and other officials from the Ports and the Confederation drinking coffee in the archives’ search room before we all went round to the seminar room where Sarah had on display a selection of custumals, including those from Tenterden and New Romney. However, before the Cinque Ports dignitaries looked at them, I gave a presentation on ‘Rethinking mayor-making and other civic ceremonies in the Kentish Cinque Ports’, although I did crossover into Sussex as far as Rye during the talk, and Winchelsea in the discussion afterwards.

This was a nice tie-in because unlike many other medieval English town custumals, in the majority of cases for the Cinque Ports, the election of the town’s civic officials forms the first item. Ok, the level of detail recorded varies but there are 6 key elements, such as the use of the common horn to notify the commonalty about the forthcoming civic election, thereby casting an aural net around the town, the role of the commons in the election process, the use of civic paraphernalia – keys, horns, staves, wands, chest; the venue and timing – linked to fishing seasons, Dover and Sandwich to the deep-sea herring, autumn season. Now for some of this I was drawing on the doctoral work of Dr Justin Croft, who did his PhD on these custumals, before turning to the civic elections themselves.

For the central theme that ran through everything was that worship in the context of these elections needs to be seen as the relationship between the term’s two meanings: religious observance and civic honour. Using this and the detailed descriptions in the custumals of Dover and Sandwich, I looked especially at the role of the church building (or churchyard – see Folkestone, Rye and Tenterden, and more on these when I revisit the topic in May) in the civic election process, and how it was understood by different audiences – the port officials, the commonalty as a whole, and outside lordship.

Of course, such perceptions concerning audience, the gaze and notions about authority, authenticity, antiquity etc are not articulated per se in the civic records, but I drew on the actions of Clement Stuppeny jnr for his (and his uncle’s ordering) of first Clement’s grandfather’s tomb and then the re-ordering of Clement’s great grandfather’s tomb, especially the alteration of the brass inscription.

Turning briefly to the holding of civic courts in these same ecclesiastical spaces, which didn’t occur throughout the period as some Ports built guild or court hall, albeit even then the civic officers remained or returned to their church in some cases, as at New Romney. We looked at how wall paintings such as the Last Judgment would have highlighted the ‘link’ between earthly and celestial justice that again would have been understood by both producers and consumers.

Following questions and discussion, the Cinque Port dignitaries looked at the documents on display before Sarah Stanley took them on a tour ‘behind the scenes’ to see the archives storeroom. At this point I left them, but as far as I could tell it had all been extremely successful.

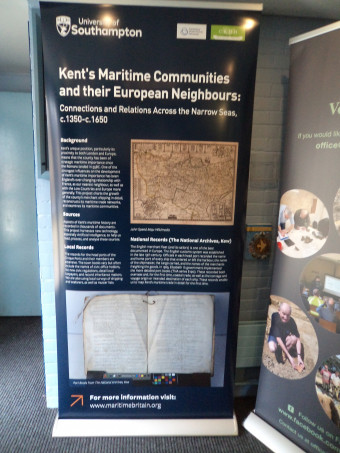

Moving back in time Jason, Mazzocchi, Kieron Hoyle and I met Martin Crowther at the Dover Museum early on Saturday morning. Soon after Dr Craig Lambert and Dr Robert Blackmore arrived and while we set up the exhibition banners on aspects of ‘Medieval Dover’, and ‘Migrants’, ‘Merchants’, and ‘Mariners’, Martin organised the laptop, projector and screen. We were joined by Jon Iveson, Curator of the Museum, and Catherine Holt, also from the Museum, while Dr Andrew Richardson set up his Isle Heritage pop-up banner and a display of books – the conference proceedings following the Sachsensymposion in Canterbury in 2017, for which Andrew was one of the organisers and editor.

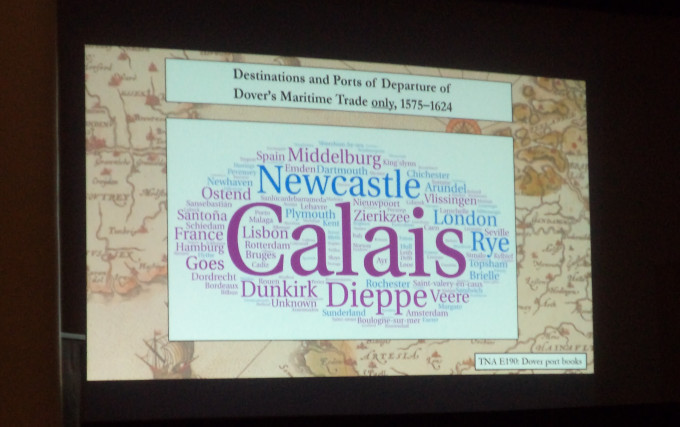

Our almost seventy-strong audience settled into the Community Cinema at the Museum and having done the usual housekeeping announcements and introduced the speakers, I handed over to Craig to introduce the ‘Kent Maritime Communities’ project. He began by pointing out that it is important to situate the regional picture within the national context, and one of the sources that helps to do this are the naval payroll documents for specific military campaigns that provide evidence regarding the ships requisitioned by the Crown, how long they served and the financial commitments they engendered and from this it is possible to examine merchant shipping over time. Other valuable sources are the customs accounts, which cover overseas trade, and from Elizabeth I’s reign the port books, thereby adding coastal trade that was always more important, perhaps around 80% of the trade. These are fantastic resources, albeit somewhat daunting in terms of the sheer number of port books – 20,000 books survive, but the wealth of information is fantastic including voyage details, cargoes, ship names, the names of ship masters and merchants, as well as the level of taxation paid. Thus, one of the products of this project will be the mapping of trade, and the activities of named ships and ship masters which will offer a much better understanding of just how such networks functioned.

As Craig said, such database projects back in the 1990s were in their infancy, for it was the arrival of Access and Excel that meant researchers could dispense with index cards, the only way prior to this, and indeed two of my contemporaries epitomise this because one stuck with such methods while the other used an Access database. However, matters have now taken another giant leap forward and the sheer volume of these documentary riches has meant it has become apparent that researchers need to find ways of employing new computing techniques in the form of AI to handle this amount of evidence. Firstly, rather than RAs spending years transcribing documents in the archives, researchers now take digital photographs (one of the issues the project faced was that the port books were infected with a nasty mould and therefore the RA had to have a mask and protective clothing etc while he photographed the individual pages) and the new step is to start teaching computers to transcribe these photographed documents. Now this is a slow business involving lots of checking because initially machines cannot recognise letter forms, abbreviations, faded documents etc, but by doing this again and again and again, Craig and Rob have got it to 97% accuracy and thus are in a position to start feeding very large numbers of documents into the system, while still making sure that this level of accuracy is maintained.

This has many advantages but is only the first part of the process because the information in each entry in the port books needs to be broken down into its constituent parts to be entered into the database. The AI system that does this is Doccanno, and it too needs to be taught how the entries are formulated and thus what in a sense goes where. The system also allows researchers to clean up the data through checking and by putting both systems into operation, regional and national projects will be able to generate ever increasingly sophisticated datasets, maps and other means to gain better understanding of traders and trade in past centuries.

This was a great introduction to the project and its challenges and successes, and I followed Craig by exploring the ‘Migrants’ of the conference title by looking at Kent as a ‘gateway county’ in the 15th century. Using both the data from the AHRC-funded ‘England’s Immigrants’ project and evidence for Kent’s archives, I discussed the distribution of known aliens across the county over this period, what we know about where they had come from, and the relative numbers involved by place of origin. Moreover, while some such as the Genoese who settled in Sandwich from the 1430s, in a few cases for decades, were merchants and their factors or commissioning agents, others from mainland Europe were more likely to be craftsmen or producers, beer being a favoured commodity. To a degree this might have been expected to place them in competition with their native neighbours, but opposition in the form of local civic ordinances only seems to have come in the last decades of the century when economic conditions were probably more challenging.

Looking at other aspects of the lives of these mainly male migrants, some had come with their wives, and occasionally even with at least one child. Using the Kent records, it is also possible to identify some who seemingly married local women, although the next generation might marry another second-generation migrant. Such networks are also visible in terms of servants, but of course some found work in native households, while others were employed by civic authorities, especially on the town wall rebuilding campaigns at Dover and Canterbury. Thus, Kent was indeed a gateway county during this period, and while some settled in Kent, it is worth remembering that the pull of London was often as significant for these immigrants as it was for the county’s native population.

After a break during which attendees could look at the exhibition banners, talk to the speakers and/or go out for refreshments, Kieron gave her presentation on the Maison Dieu and the sea. As she said, this medieval hospital had been established to provide short-stay accommodation for poor pilgrims almost all of whom had presumably arrived in Dover having travelled across the Channel. Indeed, Dover had sought to monopolize this passenger trade through royal statutes, although that rather suggests the local authorities were not always as successful as they had hoped.

Having come under royal patronage from early in its history, it is perhaps not surprising that the penultimate and final master of the hospital before it was dissolved under Henry VIII should have been active in terms of trying to revitalise Dover harbour. For by the late 15th century the harbour was suffering from the effects of longshore drift and Sir John Clark’s remedy was to move the harbour westwards to form a pool below Archcliff that was called Paradise by building a pier into the sea to stop the shingle. Although initially successful this was short-lived and the harbour was again experiencing problems which meant the Sir John Thompson, Clark’s successor was keen to present his own plan. Thompson was apparently very persuasive and gained both Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII’s approval, but he was less popular locally, spent well over budget and seems to have viewed the Maison Dieu as little more than a store for his harbour works. Thus, even though his pier and jetty building helped, it was short lived and the harbour was again in trouble within a couple of decades.

Elizabeth’s reign witnessed complaints about the state of the harbour and a commission under Lord Cobham investigated the problem to try to find a solution. However, as Kieron said, the plan was seen as far too costly and matters were shelved. Thereafter, other plans were put forward, as well as suggestions concerning how such harbour works could be financed, one of the most notable contributors to these debates being Thomas Digges, who as a local landowner, MP and member of the Kentish gentry, was able to work with those from Dover and London. Furthermore, he had visited several Dutch harbours and had a better grasp of surveying than his contemporaries. Yet, he was not the only person who thought he had the answer and the wrangling over the best approach was not resolved until 1583 when it was decided that the type of sea walls used on Romney Marsh might be both far cheaper and more effective. This was fine but as before Dover was not in a position to ensure that the town could finance the necessary maintenance, the civic authorities surrendering the harbour to the Crown in 1606.

The first presentation after the lunch break was given by Jason who explored the lived experiences of certain merchants and mariners in late Elizabethan and early Jacobean Faversham to illustrate the web of relationships and networks within the town, across its hinterland and as far afield as London. Such men as members of the Fraternity of the free Fishermen and Dredgermen of Faversham were involved in this trade, but were also likely to be grain merchants, landholders and farmers, as well as being members of the civic authorities. Thus, they were central in terms of local politics, as exemplified by the long-running dispute over control of the oyster grounds with the men of Milton, conflict over boundaries leading to the production of three maps, now on display at the exhibition at Faversham.

These maps, like the earlier map of the Kent coast for Henry VIII with its crane and houses at Faversham creek, offer a sense of place, of identity and belonging. Such ideas are similarly pertinent in the wills made by this elite group within Faversham society, and Jason drew on several examples by way of illustration. Among these was Robert Colwell who bequeathed gold coins called angels to be made into rings as acts of remembrance, such items being of worth and worthy for both donor and recipient. Another was Christopher Finch, four times mayor and steward of the Admiralty Court whose network of relations can be seen through his having a lease of property at St Ellens in London, for this one-time nunnery was primarily in the hands of the Worshipful Company of Leatherworkers. Consequently, as Jason noted, the interdependence between province and centre, Faversham and London was, and would remain, a key factor that influenced matters relating to kinship, neighbourhood, and community.

Using material from the project’s database, Rob explored how the various ports in the county fitted into Kent’s coastal and overseas trade networks between 1450 and 1650. As he said these need to be seen within the context of the considerable changes that took place in society, starting with the Black Death, demographic changes in the late Middle Ages, the state of the economy and matters relating to social mobility. Furthermore, Kent was considerably affected by Anglo-French hostilities, as well as civil war, all of which had implications for trade in all its forms. To illustrate how these factors affected agriculture, manufacturing and trade, Rob looked at several different commodities including cereals, cloth – both the old and new draperies, coal and lime, as well as luxury goods through a series of tables and graphs.

Then to complement this quantitative approach he offered the example of the experience of James Hugessen the younger (1575-1646) of Dover who, in 1624, on a voyage back to his home port from Flushing had been captured, along with the ship and cargo, by a Spanish frigate and taken to Ostend. Moreover, Hugessen not only had his cargo taken, but his captors wanted some of his clothing, including his trousers. Such an experience exemplified the potentially dangerous nature of such overseas trading and that merchants were not immune from getting caught up in political events and thus can be envisaged as agents of state power.

Following the afternoon break, Craig gave the final presentation before the roundtable, exploring Kent’s ships and mariners from the early 14th century through to the early 17th century. He took as his premise that the antiquarian view that the Cinque Ports had been in a state of decline from the reign of Edward II onwards and were of little importance by the later Middle Ages is not borne out by the data from such sources as the naval payrolls and the wardrobe books. Rather these point to the continuing importance of some of these ports as the providers of considerable numbers of ships and mariners.

For the later period, the port books give an even clearer picture of ships, ship masters, cargoes and voyages. Additionally, there are several surveys from Elizabeth’s reign that provide excellent snapshots of the situation at the various ports. These can also be supplemented from data from the muster rolls, and when taken together they demonstrate the flexibility, complexity and resilience of these maritime communities. For often these mariners were engaged in a variety of occupations and such multifunctional households provided a degree of security – not all their eggs were in the one basket. Similarly, having shares in several ships was not unusual, and women, too, often widows, were part of this share system.

Like Rob, Craig finished with a case study, and this use of quantitative and qualitative approaches is something that will be a feature of the book from the project, which hopefully will be published in 2025. So thanks to everyone who made it such a successful day.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1843

1843

Really enjoyed the Migrants, Merchants and Mariners in the Kentish Cinque Ports talks in Dover, which had some excellent speakers and was very much enjoyed by a packed audience. More of the same!

Thanks Martin, glad you enjoyed it.