I thought I would begin by reporting that we sent our roundup of pre-modern Kent and Canterbury online resources to Dr David Rundle on Monday and hopefully soon it will be on the Kent MEMS Lib. As a further development of this idea, Dr Diane Heath and I, in conjunction with Michelle Crowther (CCCU Learning and Research Librarian), will start adding modern sources to form the CKHH Lib. In this we will have a section on museums in Kent that have a virtual presence with useful material for researchers, including a virtual tour of the Folkestone Museum compiled by a team at the museum with Martin Crowther. This all looks very exciting! As does the CCCU Bookshop’s new online facility: https://bookshop.canterbury.ac.uk/

Now before I get onto this week’s topic, the Kent History Postgraduates had their fortnightly catch-up meeting yesterday. Sadly, we were somewhat depleted as a group because Lily has been unwell, Janet had intended to join us but experienced IT issues, and Kieron is feeling slightly better but not yet well enough to be part of the meeting. However, I am hopeful, confident is probably going too far, that we will have everyone next time!

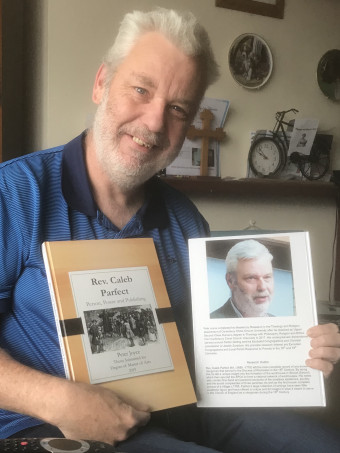

As I reported last time, Peter Joyce has successfully completed his MA by Research on the Rev. Caleb Parfect MA, which is a great achievement given a background of some serious issues beyond his control during his studies. To mark this success and to thank several people who gave him a considerable amount of help in various ways along the way, he has had the thesis printed, and quite rightly was keen to show the group the new book. In terms of what else he has been doing, he noted that because the Rev. Caleb was instrumental in the setting up of the SPCK, he has been engaged in various discussions surrounding the issue of slavery.

Jane, too, reported that she had been drawn into certain conversations respecting such matters due to her professional activities, as well as having to deal with several health issues. However, in terms of her own research on Tonbridge Priory, she has been following up her earlier work on the 12th-century charters, especially the witness lists. Consequently, she has started exploring the DEEDS: Deeds of Early England Data Set at [ https://deeds.library.utoronto.ca/ ] that Dean had mentioned at our previous meeting, as well as the section on medieval ‘hands’ or writing styles on the MEMS Lib site.

Maureen has also been looking at documentary sources because Staffordshire Record Office have managed to send her one of the account rolls they hold for Tonbridge from 1445/6, for by that date the town was in the hands of the Staffords. Although it is much less detailed than the 14th-century accounts, it will offer useful comparisons regarding the level of return the family was receiving from their Tonbridge lands and other assets. Alongside this work, Maureen has started on the PCC wills and currently is working on those from the early 17th century, and one particularly interesting will was made by John Stockwood, the local vicar who had previously been the headmaster at Tonbridge School. This clergyman was of a strong reformist persuasion and had written several theological books, as well as preaching twice at St Paul’s Cross in London, and subsequently publishing his sermons. He also adopted an anti-theatrical stance, which is especially interesting considering Tonbridge was one of the very few places outside London that had an early theatre.

Tracey, too, has been busy and is continuing to work on her religious patronage chapter, looking at wills made by women from the minor noble families of east Kent, especially from the de Cornhill family in relation to the Lukedale chapel. Her work on the manor of Wyke is similarly keeping her busy, and she has been exploring this both in the field and through maps and LiDAR, again following recommendations from others in the group, especially Lily. She has sent a copy of her findings to Andrew Mayfield, KCC’s Community Archaeology Officer, and is hoping to hear his ideas on this soon.

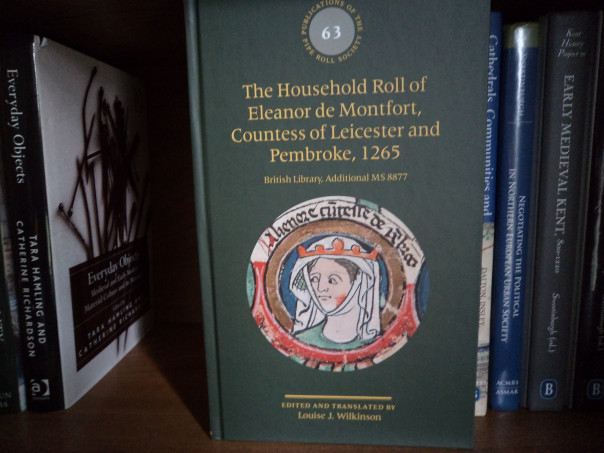

Now that he has all his books again and has finished marking and other teaching activities, Dean has been working on his thesis. At present this is primarily editing, but he has been exploring Professor Louise Wilkinson’s new edition of Eleanor de Montfort’s household roll for 1265. This has just been published by Boydell for the Pipe Roll Society and is a splendid addition to 13th-century studies, especially on Kent and its role in the baronial wars of the period, as well as the economy of this important Cinque Port. Dean, too, has been involved in current debates because his doctoral research can be seen as being within ‘minority history’.

Another issue that is related but also goes beyond matters of race is that raised by Marcus Rashford in his great campaign this week, where he was prepared to use his own childhood experiences to draw attention to the need to help disadvantaged families during the summer holidays. Taking this topic as my cue, I thought I would look briefly at some evidence about the poor in late medieval Sandwich. However first I think it is worth mentioning John Henderson’s note of the three forms of poverty he saw in his work on Renaissance Florence: endemic (the elderly and/or chronically sick), epidemic (those suddenly forced below subsistence level by severe dearth or epidemic disease), episodic (life-cycle poverty).

So what was happening in Sandwich? And today I’m generally going to ignore the town’s four hospitals. Firstly, obviously the town’s poor people were not a homogenous group, but I think it is worth noting that an almost complete tax list from 1513 named 14 paupers, with a further four names crossed out, as well as 248 persons assessed at the lowest level of 4d, who perhaps were, had been, or would be among the epidemic and episodic poor during their residence in Sandwich. With no national system to help the poor, the local civic authorities seem to have adopted a 2-pronged approach: aiding those who were from Sandwich, primarily by regulating the prices of essential commodities such as wheat, malt, meat and tallow for candles. However, quite where Thomas Fode, the common bedesman, as a favoured member of the resident poor fitted is unclear, but presumably he was expected to pray for the civic authorities as his benefactors.

The second prong comprised removing the ‘foreign’ poor when they posed a threat to the town, such as the more rigorous curfew regulations adopted in 1509, and 15 years later a new ordinance whereby beggars given permission to beg in Sandwich by the civic authorities had to stay at St John’s hospital in the 3 rooms at the back. This presumably meant far fewer if any sick-poor people could stay there voluntarily. Another of the town’s civic establishments may have been employed in a similar way in that the town brothel called the Galye had been set up in 1473. The four prostitutes housed there received a food allowance and accommodation, being expected in return to remain there, adhere to the regulations and to give the authorities at least a part of their earnings. Although rarely named, we do have a list from the 1490s when those there were Margaret Johnson, Marion Eliott, Denise Cordell, and Margaret Fuller.

In the later 15th century, poor people might be employed as water carriers by the civic authorities, but the town books also include cases of those seen as troublemakers, the first woman recoded as a whore is mentioned in 1465, and the first vagabond in 1483. In broad terms these numbers increased thereafter, and in 1535/6 nine people were banished from the town for various petty offences, including vagrancy. Sometimes humiliation and/or mutilation were also employed as part of the punishment, and one Scotsman called Jamy Reade, who had been caught fishing illegally at night in the town ditch, was paraded around the town before being banished for a year or given the option of the loss of his right ear.

Yet, as you may remember from a fortnight ago, funerals and other times of commemoration often included doles of food (and clothing including shoes) to poor people, while others gave money. However, some will makers seem to have given even more thought to how they could help, and often again there was an emphasis on those from the local community. For example, Nicholas Haryngton bequeathed a bed and bedding for the exclusive use of poor women from Sandwich in childbirth, firstly this was to be under the care of his wife as midwife, and then after her death by her successors in the town. Similarly, Elizabeth Engeham can be envisaged as using her local knowledge to try to help those she considered in need, naming several of the women she wished her executors to give money to for their dowry.

Other organisations that helped those in need were craft or parish guilds, and from the few surviving craft guild regulations from Sandwich, these did include care for poorer members of that occupation, as well as the used of protectionist policies. Although no parish guild accounts survive for Sandwich, it is feasible that the brotherhood of the poor at St Peter’s church, which was in existence in the 1540s, was primarily formed to help those in need there, and it is interesting that the brotherhood was seemingly favoured by men who followed the new religious ideas.

Hopefully, this brief exploration into the relationship between the poor in Sandwich and their more prosperous neighbours, as well as the local authorities, has given at least some indication of the ideas, problems and responses to be found in late medieval society.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1682

1682