Before I get to the topic for this week – food and its uses in medieval Kent, I thought I would flag up an initiative by the Graduate College if you are thinking of studying for a postgraduate degree – Taught Masters, Masters and PhD by research, PGCE and many more, at CCCU next year. The College is running online weekly sessions throughout June on Thursday late afternoons between 4pm and 5.30pm. Professor Susan Millns, as Dean of the College, will provide information about postgraduate student finance as well as how to apply for a place and what it means to be a postgraduate student at Canterbury. You will also have plenty of opportunity to discuss how you can gain the postgraduate edge and take your studies to the next level. For further details and to book a place, please email: graduatecollege@canterbury.ac.uk

This week was the fortnightly online meeting of the Kent History Postgraduate group, and much to Dean’s annoyance, it was raining in the Manchester area but still dry if not sunny in Kent! Although, as the people in Kent explained, actually this isn’t good because the south east is experiencing a drought and growers everywhere would love to have ‘his’ rain. Having establish this and that hay fever levels are similarly exceedingly high in Kent, but much lower in Manchester, as Lily testified, we moved to catching up on how people are continuing to cope. As at previous meetings, I am deeply impressed by everyone’s resilience in what remain exceedingly changing circumstances, especially for those who have family and other commitments, as well as facing continuing problems of closed archives and limited access to library resources.

Sharing a simple meal of bread and drink; Livre du roi Modus et de la reine Ratio, 14th century. (Bibliothèque nationale)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_cuisine#/media/File:Peasants_breaking_bread.jpg

So what have people been doing? As it happened Dean was again in the top left-hand screen shot which meant he started the ball rolling. He has finished marking undergraduate essays and dissertations! This means he will be able to get back to editing his doctoral thesis; however yesterday he had been looking at late-12th-century charters, but more on that in a minute. Keeping with the 12th century, Tracey reported that she had been using her regular walks to investigate the likely site of a manorial complex that had been held by one of the east Kent families she is investigating. From her observations it seems these 12th-century manors were located about 5 furlongs from the Littlebourne Road, and often there are still footpaths from the road to the manorial site, a testimony to the ancient nature of this network of paths. This sparked a discussion about the dating of structural remains when the building material is flint. Tracey wondered if people could suggest whom she might contact about dating and she received several suggestions. Thereafter, the discussion expanded to the potential value of LiDAR, and after the meeting Lily sent everyone a link to the National Library of Scotland maps, which has national coverage and can be accessed online.

Moving on, everyone congratulated Pete on successfully completing his MA on the Rev. Caleb Parfect MA, whose large collection of letters offers a unique and full insight into what it meant to serve in the Church of England as a clergyman in the Rochester diocese during the 18th century. Pete is still part of the CCCU chaplaincy team, and he is deciding which direction he wishes to follow next. Also working on north Kent, Janet took us back to the Middle Ages. She has her review meeting with her 2 supervisors coming up at the end of June and is sorting out the chapter structure of her thesis. Currently she is exploring matters relating to hunting and parks in the Bexley area in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Turning to Tonbridge, Maureen said she had managed to download the 16th-century PCC wills from TNA for the town. She has started working through them and has 2 linked to the local cloth industry, an important Wealden activity. Going earlier, she been looking at the England’s Immigrants database and has located the names of 39 immigrants who were in Tonbridge in 1440. This brings me to Jane and the charter Dean was looking at. As the earliest in the Tonbridge priory cartulary, Jane is hoping that it will help her establish just which of the de Clare’s founded the priory. The discussion centred on how feasible it is to date handwriting between the early and late 12th century, and the consensus was that this is a late century example. However, all agreed that probably a better test regarding dating it to try to identify the witnesses and to match them to other contemporary charters. Although Jane only has limited comparable charter witnesses, Dean suggested that it might be worth exploring the University of Toronto’s charter database, and he said he would find the link for her. In this spirit of co-operation Pete said he would make enquiries regarding Dean’s dilemma about many of his belongings still being in Kent and his desire to take them home. Thus ended another catch-up with a great spirit of group solidarity on view yet again!

In some ways this same theme of individual and group co-operation has been much in evidence regarding people offering to get food supplies for the elderly and those shielding, food banks working overtime, and pubs, restaurants and other food outlets supplying meals for health and care workers, as well as for the vulnerable. The common feature of food is no accident for as a basic necessity it means so much in so many ways, as attested by its deployment by all the great religions through abstinence and feasting, through symbolism, through notions of caritas and common weal; and the myriad ways it is used through gift-giving and reciprocity.

Consequently, it seems wholly fitting topic, and here are a few examples I have spotted over the years in various documents from medieval Kent. As anyone who knows me won’t be surprised to see, I am starting with cakes, although not chocolate because it wasn’t around then – sorry Harriet! Now Giles Love of Dover in 1514 made several food bequests to St Mary’s hospital in his will, including 20 bushels of bay salt. However, I just want to remember his directive that his gift of plate and a house in Bygon Street to the hospital brothers placed an obligation on them to celebrate annually at his obit 6 masses by note. In exchange they were to receive 2s, 13 poor men and women were each to get a penny dole, and the master and brothers were to spend 2s on fresh cakes and the act of eating them was to be accompanied by their remembrance for his soul. A scenario that is easy to imagine as they gathered around to enjoy this annual treat.

As in more normal times, eating following funerals was an important part of medieval culture, and in addition to obits (anniversaries of the day of death), the month’s mind was another time of commemoration and to aid the soul through purgatory, which, too, often involved providing food for family, friends, neighbours, and most especially the poor. Wheat bread and ale were the staples – reminders, also of the Last Supper and the mass, but some testators went beyond these commodities. For example, John Philpott of Ringwold in 1476 intended that his executor would organise dinner for his neighbours and poor people after his funeral, using 12 bushels of wheat, 20 bushels of malt and sufficient meat at the executor’s discretion. In contrast Sir Robert Mariott the vicar at River near Dover (1522), was more precise and at his month’s mind, as well as the wheat bread and double beer, the poor and those who had come to the requiem mass were to share half a beef costing 10s, 2 sheep, 2 pigs and 2 geese. Whether this was Kent’s answer to the Cornish pasty, I don’t know, but at his month’s mind Robert Troppam of Goodneston, in 1537, he wanted a bushel of wheat and a bushel of barley to be baked and brewed for the bread and ale. This was to be taken to his parish church where the dirige and 5 masses were to be celebrated for the benefit of his soul, the poor people to then enjoy this feast with a wether sheep that had been cooked and made into pasties. While for those living near the coast oysters might be provided, Garard Johnson of Milton near Sittingbourne (1528) intended that those attending the masses at his funeral and month’s mind would thereafter enjoy a wash of oysters with their bread and beer.

Such giving of ‘food to the hungry’ and ‘drink to the thirsty’ might be linked to a more specific community such as a hospital. As in the case of deceased brothers and sisters at St John’s hospital in Canterbury where bread, ale and cheese at funeral feasts seems to have been the recognised provision. Indeed, even those who in life had not been members of this community, in death were at times keen to join through the bequeathing of such provisions, as Joan Bakke did in 1500. Hospital communities also celebrated their patronal feast day, but equally remembered festivities such as Christmastide, and those at St Bartholomew’s hospital, Sandwich, went to dine at The Pelican on Twelfth Night, and every Sunday evening drank ale together to remember their founders and benefactors.

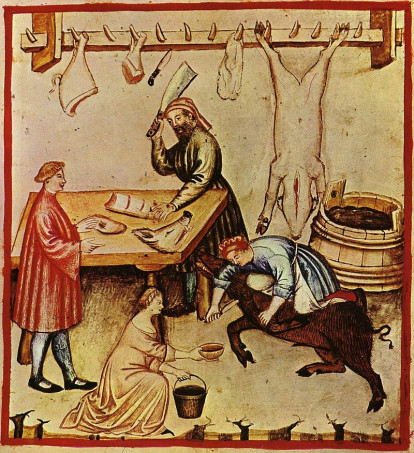

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_cuisine#/media/File:13-alimenti,carni_suine,Taccuino_Sanitatis,_Casanatense_4182.jpg

Craft and town guilds and parish fraternities met similar needs, through provisions on the death of members, and also at annual feasts, such as the Canterbury guild of shoemakers who having attended their patronal mass on the feast day of the Assumption of Our Lady and also on the feast day of SS Crispin and Crispinianus at the Austin friary church, enjoyed the guild warden’s dinner. Members of the Corpus Christi Guild at Maidstone were even more lavish at their annual feasts, while at Sandwich the annual St Bartholomew’s procession to the civic hospital’s chapel of the same dedication, was followed by high mass and a feast. At the level of the parish, ‘give-ales’ do not seem to have been as common in Kent as Somerset, but among those who did remember such festivities was John Upton of Westcliffe who wanted a quarter of barley malt for the ale and a similar amount of wheat for the bread, the celebration to take place at midsummer on the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, perhaps accompanied by a bonfire. To a degree, others seem to have appropriated the idea for more personal commemoration: in her will Etheldreda Barrowe of St John’s in Thanet wanted a give-ale annually at her obit forever.

Even though I haven’t seen any bequests of honey to be given at any of these feasts, bees do occur in will bequests. For example, John Boldyng of Lydd wanted after his death all his bees to be divided equally among his children at Michaelmas, and then at that Christmas his wife would have the best hive, as well as a range of foodstuffs including 3 bacon flitches, all his butter and 4 cheeses.

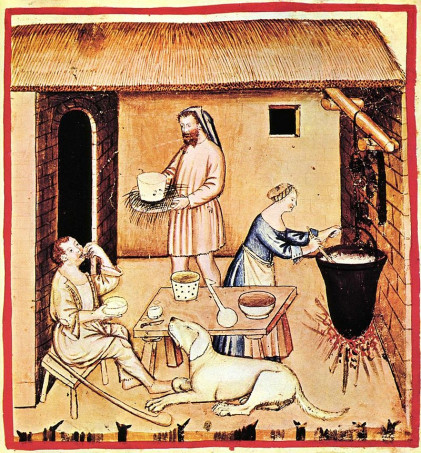

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_cuisine#/media/File:9-alimenti,_formaggi,Taccuino_Sanitatis,_Casanatense_4182..jpg

Even though most of these cases relate to individuals, corporate, and especially civic giving of food and drink was extremely important in medieval Kent. Consequently, I’m going to finish with a couple of examples from Canterbury. As a gift to the duchess of Exeter in 1463, the mayor gave her oranges costing 2s 8d when she came on pilgrimage to St Thomas’ shrine with her brother, King Edward IV. Whether these sweet oranges had come to Sandwich on one of the Venetian galleys from Spain or Portugal, we don’t know, but it seems feasible. Yet, more often it was various wines, a range of fish or other delicacies, including swans, that the city authorities presented to important guests. During the city’s long-lasting quarrel with St Augustine’s abbey over certain property rights, the two senior crown appointees who conducted the hearing in Canterbury stayed at the Austin friary on two occasions in 1476, and each time the corporation lavishly entertained their guests there. Thus, food has and is a vital medium whereby society can come together on all types of occasion, and as one commentator reported recently, some of the local groups that have sprung up across the country in the wake of the lockdown are intending to continue their food-giving activities once ‘”this is all over”.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2775

2775