Some encouraging news, it seems likely that we will receive the necessary funding to be able to produce the 2nd phase of the ‘Medieval Faversham’ exhibition. Consequently, Dr Diane Heath is checking what we would like to add to the items we didn’t produce last time when the funds ran out. These will include about three more exhibition boards, such as Faversham Abbey’s ‘Book of the Dead’. We also hope to have several more pop-up banners that have the added advantage of being flexible regarding where they are displayed, two life-size figures of King Stephen and Queen Matilda, and items for the ‘Young Medievalists’ corner. All being well, the exhibition will open early July, but as soon as I know more I’ll let you know.

Since the last blog report, Professor Louise Wilkinson and I attended Canterbury City Council’s Heritage Strategy Plan consultation meeting with other representatives from organisations interested and involved in heritage locally, including Paul Bennett from Canterbury Archaeological Trust, Andrew Dawson from the Marlowe Theatre Trust and Lyndsay Ridley from The Canterbury Tales. The city council is at the early stages of this process and the brain-storming meeting was the second the council had held to see what ideas people have and whether there is any consensus regarding what and how things should be done. To ensure there was plenty of discussion, the organisers had designated which discussion table each participant should join, which meant that at my table the organisations represented included heritage/history groups from Harbledown, and from Littlebourne and neighbouring villages, from the Marlowe Theatre, as well as a representative from the city council.

Arden of Faversham’s house – where he was murdered.

To begin the process Peter Kendall (Historic England), outlined how this initiative was coming out of the National Planning Policy Framework. He also highlighted that there was no blueprint that fitted all places and that it was equally important to bring in undesignated heritage assets, as well as those already designated, and additionally non-tangible ones, such as Whitstable’s oyster festival.

Rosie Cummings, the city’s part-time conservation officer, took up some of Peter’s points by underlining just how many listed buildings there are in Canterbury and district (in excess of 1880), its 97 conservation areas, its value as an area of archaeological importance, and its role as a UNESCO World Heritage Site encompassing St Martin’s church, St Augustine’s abbey and Canterbury Cathedral. She noted that the intention is to have a strategy formulated and adopted by early next year.

With these ideas in mind, Rosie gave out the first question for discussion: ‘what is the role of heritage now and in the future’, with a view to each group producing three key points. As you might expect lots of ideas were put forward, all noted down by the city council representative, but for my table our key points were ‘Protection’; ‘Education’, and ‘Connecting people and places’. Further questions followed, ending with the final request: ‘what would you like to see in the Strategy?’ This provoked a considerable discussion at my table and among the ideas voiced were: priority of heritage over commercial building; co-ordination between interested groups; identifying parts of the area that need help; short-term as well as long-term goals; preservation and protection; strategy as an economic driver; and bringing history to the fore.

Detail of Eastbridge hospital from Map 123 (Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library)

This was all interesting and it will be fascinating to see what happens next in the drive to develop a workable Heritage Strategy – something councils are doing across England. Yet as at so many such meetings probably what was far more useful for the organisations and groups was the chance to talk to other people. This was made easier because there were two refreshment breaks, and among the people I spoke to were representatives from the University of Kent, English Heritage and the Canterbury BID, which has had considerable success over the last few years with its annual staging of the Medieval Pageant in early July. This year the Centre will again be taking part, and, as last year, will be based in the Greyfriars Gardens.

So that is the ‘heritage’ part of the Centre’s name and this week the ‘history’ part comes from the Kent History Postgraduate Seminar where the two presentations were given by Andrew Leach and Kevin Field. They are both working on Masters by Research, but on very different topics and time periods. Andrew, working under Louise Wilkinson’s supervision, is looking at two noble families, one primarily based in Lincolnshire, the other in Kent and this time he focused on the Crevequer family of Kent. Although his principal period of interest is the 12th and 13th centuries, he introduced the family starting with its first known ancestor Hamo ‘Dentatus’ who was Lord of Torigny, Creully and Evrecy. However, it was his son Hamo ‘Dapifer’ who was with Duke William at Hastings and thereafter the family held lands in Kent as well as Normandy, Hamo becoming Sheriff of Kent from 1077 until his death in about 1088. As a family, as Andrew noted, they were very keen on the names Hamo and Robert which means that at times it is difficult to trace which individual is involved.

Rosie Cummings and Rupert Austin (Canterbury Archaeological Trust) discuss the state of the brickwork

Like many noble families in the 12th century, Robert (1) was a religious patron and was caught up in the civil war between Stephen and Matilda, being one of King Stephen’s supporters. The centre of the family holdings was at Leeds in mid-Kent and it was close to Leeds castle that Robert established a priory of Augustinian canons in the early 12th century. The canons did receive lands from their patron, but even more Robert recognised their pastoral role by granting them 7 churches from within his baronial lands. His example was followed by his brother and his son, both men each granting a further 2 churches, as well as more land, mills, salt and various tithes, which meant that the priory became the wealthiest house of its kind in the county. Indeed, successive priors were able to overcome the loss of their Crevequer patrons, who were on the ‘wrong’ side during the Second Barons’ War of the early 1260s and were among the defeated rebels after the Battle of Evesham.

Yet it was not only the main branch of the family who were religious patrons and a minor branch, but again named Hamo and Robert, were lords of Blean and major benefactors to St Thomas’ (Eastbridge) hospital in Canterbury. As at Leeds, one of the main grants Hamo gave to St Thomas’ was the advowson of Blean church, as well as land and hen rents. His mother, brother and son followed his example, and apparently so did some of his tenants. Nor was this the only Canterbury hospital aided by Hamo, for among his charitable/pious beneficiaries was St James’ hospital, and he also made gifts to St Gregory’s priory and Christ Church priory.

As Andrew explained, such gift-giving provides ideas about patronage in terms of grants for one’s soul and the souls of relatives, as well as ideas about the value and use placed on wealth. This sparked a discussion among his audience that especially focused on matters of lordship and how this was expressed through gift-giving, lordship seen to function with respect to both those above and those below the Crevequerers. Concerning the former, their relationship with the Crown was considered, but also the role of archbishops. For as Andrew had shown, several archbishops had been involved by confirming grants of churches to Leeds priory, while St Thomas’ hospital was under the patronage of the see by the 13th century, and Blean abutted the archiepiscopal manor and Hundred of Westgate. This brought the debate around to ideas about church patronage across all the Crevequer estates, and after the meeting having remembered how to access the Taxatio database, I sent this to everyone because it is likely to be useful to others as well as Andrew: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/taxatio/

Going under Canterbury’s Eastbridge

Our second presentation by Kevin Field, supervised by Dr John Bulaitis, took us to the 19th century and the problems experienced at three rural workhouses in Canterbury’s hinterland when they were confronted by poor people suffering from highly infectious diseases such as cholera, typhus, diphtheria, smallpox and scarlet fever. Kevin is investigating the East Kent Unions of Blean, Bridge and Eastry, and what was highly striking from his map was that the Blean workhouse post 1834 was at the western edge of the area covered by this Union, which meant people would have been expected to travel considerable distances to get there. For example, Kevin’s first case study of Robert Reason, who was sent to the workhouse in Blean in 1849 from Canterbury because he was suspected of having cholera, although the official inquiry considered this was too far to travel, in actual fact the distance was less than if he had travelled from the eastern section of the Blean Union’s jurisdiction. It is also worth mentioning that the poor man died soon after he was admitted to the workhouse.

As Kevin explained, there was often a tussle between the workhouse Guardians who were far less keen to admit poor people suffering from infectious diseases and the Medical Officers who thought the workhouse was better than ‘treating’ them in their own home where infection was likely to spread rapidly. Part of the problem was the limited provision of spaces in workhouse isolation wards and the absence of isolation hospitals. Added to this were the poor conditions of some of these rural workhouses and that frequently there was little general desire to make substantial improvements, cost being a major concern.

Consequently, advancements were a piecemeal affair, for example ventilation did improve in response to particular cases and recommendations. Food, too, was seen as an important factor, and on occasion a better diet was provided, although this might only be a short-term measure. The 2 major outbreaks of cholera in 1849 and 1854 did stretch the provision to breaking point, and in 1872 when 2 people with smallpox were admitted to the Blean workhouse there were no isolation wards available, which meant the Guardians took the drastic step of renting out 3 cottages for them. Two years later Blean did invest heavily, the Poor Law Board approving the Blean Guardians expenditure of £3,564 to build a new hospital for the workhouse and new wards for the sick and infectious.

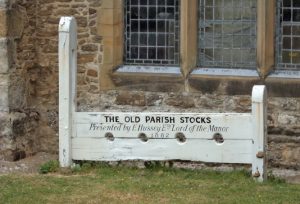

Parish stocks at Marden

Kevin’s case studies started a discussion about these changes and whether Canterbury had better facilities compared to these rural workhouses, but which they were not prepared to share even when the person was seemingly from ‘their’ area. Janet Clayton mentioned the problems that had been experienced at Bromley workhouse during this same period as a useful comparative example. We also considered the introduction of vaccination in the case of smallpox and the role these various Medical Officers had played in the implementation of such schemes.

Bringing the meeting to a close for the session as well as for this academic year, it was interesting to note that even though Andrew and Kevin had been looking at very different periods and seemingly very different topics, there were a couple of common themes – the management and funding of (charitable) institutions and the role of patronage.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that, with others, several members of the Centre: Professor Jackie Eales, Drs Martin Watts, Diane Heath and I have written short pieces on different aspects of Canterbury and the World Heritage site for Michelle Gallagher’s (Department of Marketing and Communication) feature in Inspire – I’ll let you know when it comes out.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1553

1553