Seeking to engage younger audiences and to show just how exciting medieval and early modern (and modern) studies can be is becoming an increasing important part of the Centre’s activities. There is the partnership with The Canterbury Tales for two activities on the Friday of the Medieval Canterbury Weekend, story-telling in the afternoon: http://www.canterbury.ac.uk/arts-and-humanities/school-of-humanities/medieval-canterbury-weekend/medieval-canterbury-weekend-2018/chaucers-tales.aspx In the morning at Waterstones Saturn, the wonderful green dragon, will be looking for his lost roar between 11 am and midday, do come and help him find it.

Additionally, the third group of sixth formers will be going to the archives on Monday for a workshop on early Tudor society, and I happened to see Professor Carolyn Oulton (Creative and Professional Writing) on Monday and she was talking about the project she is putting together at Canterbury Christ Church on crime and punishment in east Kent from medieval to modern times under the umbrella of ‘Being Human’, where again the idea is to engage youngsters as well as older people.

Helping roaring dragons

Then on Wednesday night I attended a meeting at Faversham Guildhall, chaired by Dr Harold Goodwin (Faversham Society), and heard what the 11 ‘heritage’ organisations in the town and surrounding area with the Town Council are thinking would be a valuable way of engaging visitors and the local community alike now that the Town Council has bought and is in the process of refurbishing 12 Market Place for council and heritage uses. This is still at an early stage, so I won’t go into any sort of detail but the projected use of what people agreed could become an excellent heritage hub was very interesting. If will be fascinating to see how this develops. In the meantime the Centre, especially Dr Diane Heath and Harriet Kersey are busily working on what will be a temporary exhibition in 12 Market Place on ‘Medieval Faversham’. Indeed, during the past week they have both been working of a Faversham timeline and various display boards, including the town’s custumal and chronicle, the latter also in the Faversham Custumal Book that ends with the earthquake in 1382. This earthquake was also felt in Canterbury, causing considerable damage to Christ Church Priory’s bell tower and the newly refurbished chapter house, thereby setting back the prior’s rebuilding programme that had been in full swing, including the great perpendicular nave.

Mayoral chair at Faversham Guildhall

Keeping with the notion of engaging audiences, on Tuesday I attended the Annual Becket Lecture which was given by Dr Marie-Pierre Gelin to a good-sized audience of over eighty people in Old Sessions House. In her talk, she explored the relationship between Thomas Becket and his archiepiscopal forebears, especially St Dunstan and St Alphage, as constructed by the monks of Christ Church in their pursuit of an ideal – both abbot and archbishop; confessor and martyr.

As she said, she wanted to examine three aspects: how and why the monks built up their image of the ideal archbishop who was also their abbot; how Becket became a saint within this construct, and thirdly how the community employed matters such as liturgical calendars and stained glass images to reinforce these connections to place them at the heart of the monastic community, while at the same time having an eye for the ways these would be perceived by audiences beyond the monastic precinct as the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury grew rapidly in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Of these approaches, I’m going to keep to the first two because Dr Rachel Koopmans’ new project on the St Thomas windows, which she will be starting when she returns to Canterbury this summer, will feature in the blog. This is an extremely exciting development, but more on that in a few months.

Dr Gelin before the start of her Becket Lecture

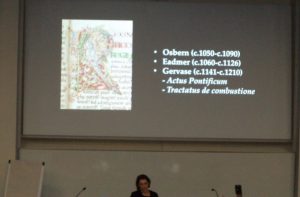

Returning to Dr Gelin’s lecture, to show the depth of continuity, she started with the pre-Conquest period, mentioning the reverence certain late Anglo-Saxon archbishops had displayed for their predecessors, such as St Dunstan’s commissioning of a life of Archbishop Oda, who like Dunstan was concerned to reform religious life in England, but her main focus was on post-Conquest hagiographical works. Of major importance among these lives are those produced by the monks Osbern and Eadmer under first Archbishop Lanfranc and St Anselm, his successor. These lives of the late Anglo-Saxon canonised archbishops Dunstan and Alphage strengthened their place within Canterbury’s history, while the placing of their relics on a beam near the cathedral’s high altar used location to demonstrate their value and significance in Norman England. For unlike the first archbishops who had been buried at St Augustine’s Abbey, the abbey becoming the site of the cult of St Augustine, and interestingly St Mildred following the monks’ translation of her relics from Thanet to Canterbury during Cnut’s reign, much to the annoyance of the men of Thanet, later Anglo-Saxon archbishops (and beyond) were buried in their cathedral church. This coup was an excellent development for Christ Church Priory, and in the case of St Alphage – martyred at Greenwich – this included the translation of his body (relics) from London to Canterbury.

Dr Gelin discusses Osbern, Eadmer and Gervase

What might be seen as the next generation of monk writers at Christ Church Priory took these ideas to construct strong spiritual genealogies that drew on the notion of the ideal archbishop as a model suitable for emulation. Amongst these writers was Gervase, and, even though he is probably best known for his narrative of events relating to the rebuilding of the choir and east end of the cathedral following the major fire of 1174, his Actus Pontifiam is an important work. Moreover, as well as covering particular aspects of Becket’s time as archbishop, it offers what Gervase saw as a significant contrast to Becket in the form of Baldwin’s and Hubert Walter’s considerable hostility to Christ Church Priory. These episodes centred on the desire by the archbishops to establish a college at nearby Hackington that, as well as depriving the Canterbury monks of ‘their’ St Thomas, would have meant they were no longer even fictionally in control of the selection of the new abbot-archbishop. In addition, there was the question of funding the new institution that witnessed an attempt to relocate certain rental revenues from the almoner at the priory to St Stephen and St Thomas’ at Hackington, which as you can imagine did not go down well with the monks.

If you are interested in this dispute and the implications for the cathedral in the late 12th century and beyond, I would recommend several of the chapters in Louise and Dr Charles Insley’s edited collection entitled Cathedrals, Communities and Conflict in the Anglo-Norman World (Woodbridge, 2011), but for Dr Gelin’s lecture the crucial point was Gervase’s treatment of Thomas Becket’s character and attributes, especially during his time in exile, the lead-up to the murder and what followed regarding the early years/decades of the cult. For Gervase’s purposes Becket’s life was challenging, but the finding of his hairshirt and monk’s habit under his archiepiscopal vestments on Becket’s body following the murder offered evidence of his aestheticism and his loyalty to the monastic life – he was a true son of the Church. Furthermore, his premonition of his martyrdom, including seeing himself as another Alphage, highlighted the saintly gift of prophesy, and while such attributes are similarly to be found among the accounts of Becket’s life and death written by several clerks from his own household, Gervase was in a sense coming at this narrative from another standpoint.

Saltwood Castle – the 4 knights left from here in December 1170

Dr Gelin’s references to Gervase reminded me of Dr Diane Heath’s talk to the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust last year, where she was drawing on her doctoral research on the medieval bestiary. Some of you may remember the blog which followed Diane’s talk on the text written by one of Gervase’s fellow monks. For Nigel Wireker, too, highlight the implications of model archbishops, harmony and continuity when placed against those seen by the monks as far from ideal who brought upheaval and chaos to the Christ Church community. Just to give you the salient points, Diane believes his Speculum Stultorum or The Mirror of Fools; that is the adventures of Burnellus the wild ass or onager, should be read as Nigel’s critical commentary on the events he and his fellow monks at Christ Church Priory experienced under first Archbishop Baldwin and then Hubert Walter, as outlined above. Nor were the monks’ problems over with the appointment of Archbishop Langton; because this led to the papal interdict on England and the monks’ exile, to be followed by the barons’ struggle against the king that similarly drew in the priory.

All of these ideas are extremely interesting, and after her lecture Dr Gelin answered several questions from the audience before Professor Louise Wilkinson drew proceedings to a close, thanking Dr Gelin for a fascinating lecture that complemented previous Becket Lectures, including that of Dr Paul Webster whom many had heard last year.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1219

1219