In many ways, I want to pick up the same theme as last week. This is because I discovered this week that among the elements within the new GCSE syllabus is the role of medieval or early modern historical sites; and that in Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 3 a local study using primary sources is one of the criterion. In my opinion, such an emphasis on a student’s own locality in the past seems a good idea because just as microhistory can be used to understand the ‘bigger picture’, so a local history study, provided it is set within its regional and national context, can be both rewarding and enlightening.

Just thinking about medieval or early modern historical sites in Canterbury, certainly there is the cathedral and archbishop’s palace, St Augustine’s Abbey, parish churches such as St Martin’s (the third element in the World Heritage Site) and St Mildred’s, remnants of two of the three friaries, the Westgate Towers and Canterbury Castle. However, what Canterbury has that really marks it out from most other towns, including London, is the survival of its medieval hospitals. For those who have walked down the High Street the obvious example is Eastbridge. This is indeed a very interesting example having accommodated poor pilgrims until the destruction of Becket’s shrine, later becoming an almshouse and school, but perhaps even more interesting and one that could be used in a study to look at even more social and political issues is the Poor Priests’ Hospital. This building is quite simply a gem. And, at least at the moment, is (even if it has been shut for large parts of the year over recent years) the Museum of Canterbury (Canterbury Heritage Museum). Consequently, it could be studied by GCSE students in a variety of ways to explore both the way the building was developed over time and how this fits into ideas about charity, poor relief, educational provision, the increasing value placed on privacy, household development to name just a few alternatives. Furthermore, the artefacts in the museum would enhance such a study provided they are presented contextually and not in a cultural vacuum, which is the danger if such materials are simply deployed as individual items.

The importance of this distinction was apparent this morning when I was joined in Canterbury Cathedral archives by a group of Classics sixth-formers from the King’s School. Having met their teacher ‘JT’ earlier in the week we had decided to use the session to explore the importance of continuity and change over time in the lived experience of these students. For example, we took the concept of how do people today identify themselves in terms of a financial transaction – the contactless credit card – and introduced the students to medieval seals. Simple you may say, and yes true, but we took this idea a few stages on. For example, because the group primarily comprised female students, we thought about just who was making the grant and we found that in the first line of this thirteenth-century charter it was Henry AND Matilda his wife and attached to the document were two seals. The seals were of different sizes and the consensus was that Matilda’s seal would be the smaller of the two. However, when asked to look for the name on the larger seal all agreed it was Matilda’s. This presented an interesting scenario because the students were well aware that in medieval times and indeed until relatively recently in law a married woman’s property would have been under the jurisdiction of her husband. Thus, Matilda’s female agency in the transaction provided a means to discuss the role and importance of customary law, the significance of different jurisdictions, and going on from this, how these would have affected marital relations in Canterbury. Taking this a stage further, the group then considered whether Canterbury was unusual and if not which other towns had similar rights for women and what this might have meant for society.

The second charter we looked at was a grant made by Eleanor of Castile, Edward I’s queen. I won’t go into the details of the gift to Christ Church Priory because the point I want to make relates to the seal itself. Her green, large oval-shaped seal is beautiful and very carefully they each touched it with a finger, a tactile experience that brought them into contact with an object that is about 700 years old. Now, these are sophisticated, highly intelligent young people for whom all the wonders of technology are part of their daily lives. Yet I felt this was a special moment, and, no, we were not going back in time like some time-traveller, but it was giving them a link because artefacts – material culture – matter, they are a route into thinking and exploring the past. Consequently, we then discussed the representation of her on the seal, what were the emblems, why was the architectural decoration important, what was she ‘saying’ about her position, her role, her identity.

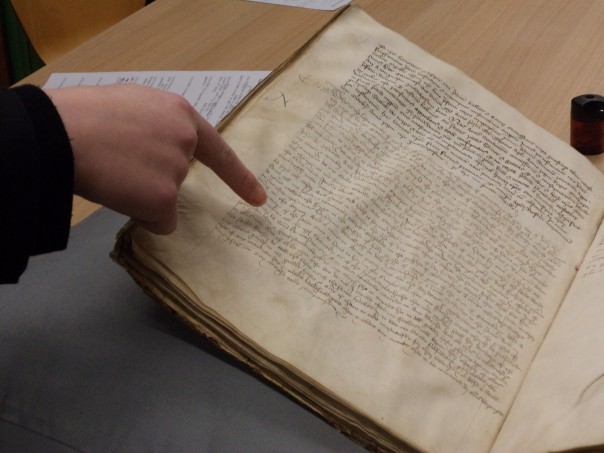

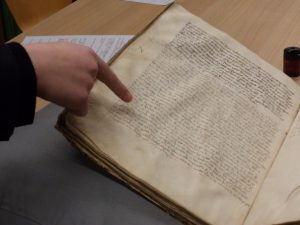

We looked at several more documents but I will just refer to two more here that continue these two themes: material culture and female agency. Within the city’s archive, there are two books which record events, many of which took place at the guildhall before the two bailiffs. However, before I come to these records, I want to mention that the books are in their original bindings of wooden boards covered by white leather. They are in remarkably good condition, but, even so, there are numerous holes made by boring insects and again this interested the students. A further connection to the past came when we looked inside the front cover because the common clerk from the late fourteenth century had noted what he presumably saw as the most momentous events of recent times. These included in 1348 the great pestilence in England and another in 1361, in 1376 the death of Edward Prince of Wales and his burial in Canterbury Christ Church next to the shrine of St Thomas the Martyr, in 1347 the taking of Calais and several dates relating to the dispute between the city authorities and St Augustine’s Abbey. Such a selection not only represent issues that mattered in Canterbury, but place Canterbury in regional, national and international contexts, just as the artefacts in the Poor Priests’ Hospital museum situate the city and its history in these same different and important contexts.

So what types of actions are recorded taking place in the guildhall? Well, this is where female agency returns because many of these events relate to will making and the bequeathing of property within the liberty of Canterbury. For the bailiffs wanted to know about such bequests, not least because the city’s custumal allowed married couples to leave their property to their surviving spouse and like all civic authorities, those in Canterbury were concerned about continuity, whether this was commercial or domestic. In 1386, one such wife who left her newly repaired four shops in the parish of St Mary Northgate to her surviving husband was Johanna Pyryton, with the proviso that after John’s death they should pass to Johanna’s daughter, another Johanna.

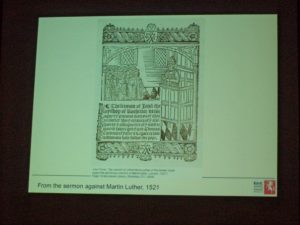

Woodcut of Bishop Fisher preaching

Just before I leave the documents we looked at, I thought I would mention another example of female agency that we explored. In one of the Christ Church Priory registers, compiled during two vacancies of the see, there are several entries relating to wills. One of these testators in 1396 was Johanna Hoo alias Goodhewe. Among her beneficiaries was her servant Johanna, but thinking about late medieval women as independent businesswomen, of even greater significance was that she was said to be her apprentice. This entry, and what Johanna received from her mistress in terms of clothing and other items, produced quite a discussion, and, by the end of the session, the students’ ideas about the place of women in medieval society had significantly changed.

Elizabeth Finn’s lecture

Finally, I just want to mention a lecture I attended this afternoon. As some of you will know there is an important connection between St Dunstan’s church just outside of the city and Sir Thomas More, the Tudor lawyer and writer. Consequently, each year the Fellowship of St Thomas More have a lecture at the AGM in February. This year Elizabeth Finn of the Kent County Archive Service gave a fascinating lecture on John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester who had been a friend of Thomas More. Rather than concentrating on Fisher’s opposition to what he saw as Henry VIII’s illegal attempt to divorce Katherine of Aragon, she provided some extremely interesting ideas about his sermons, his theological works and his activities as bishop and Cambridge academic. The attentive audience were, therefore, treated to a first-rate lecture, once again demonstrating the appetite for history in this most historic of cities.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1346

1346