I thought I would start with the press release from CCCU Marketing by Jeanette Earl about the Medieval Canterbury Weekend, which is coming up fast: https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/news/who-run-the-medieval-world-girls-medieval-women-take-centre-stage-at-history-weekend so if you haven’t seen it, please do have a look.

Next week, in fact on Tuesday evening, I believe, Dr John Bulaitis (CCCU) will be out giving a lecture again, this time at Alkham to the local history society. Then on Wednesday the Kent History Postgraduates will be meeting for the monthly presentation. This time it will be given by Jason Mazzocchi where he will be developing the presentation he gave before Easter at Dover Museum as part of the ‘Migrants, Merchants and Mariners in the Kentish Cinque Ports, c.1400-c.1600’ conference and exhibition. The report is at: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/kents-maritime-communities/ so again, please do have a look.

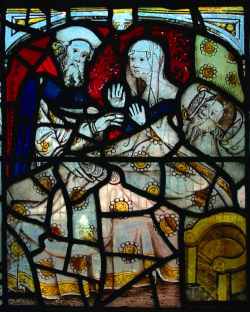

However, for this blog I’m going to bring you some ideas from the presentation I gave today (Saturday) to the Canterbury Gregorian Music Society as part of their AGM and event to mark the fact that they have sung in many of Canterbury’s surviving medieval and Tudor hospitals and almshouses. They are a great, enthusiastic group and previously having heard them sing in St Mildred’s and St Paul’s churches, it was excellent to meet up with them again. Personally, being interested more in the people who lived in these institutions than the hospital buildings per se, I had decided to kick off the lecture by using two images: ‘visiting the sick’ from the Seven Corporal Works of Mercy at All Saints’ church, York, and the Last Judgment painting from St Thomas’ church in Salisbury. I wanted these as a means to think about late medieval charity, how the good works fitted into the theology, their implications for the role of the hospital in society and the recipients of this charity – aiding the sick, helping strangers with its links to pilgrims, as well as Christ the pilgrim and the idea of the spiritual journey. This took us then to St Thomas’ painting and the saving of souls, donors seeking to be among the righteous (sheep) through the Christian’s duty to God, to one’s neighbour, to oneself. Thus, both inside and outside the hospital, through the spiritual economy, there was an ongoing reciprocal arrangement between benefactors and beneficiaries. And it was these twin images I wanted the audience to keep in mind as we moved across the Tudor period ie the loss of belief in purgatory and salvation through good works and its replacement by justification by faith where charity was the action of a true believer as an example to others.

I had decided to divide Canterbury’s hospitals/almshouses into the ‘survivors’ – those who still function today, and the ‘casualties’, none of which made it as hospitals out of the 16th century. Taking the survivors first, we have Archbishop Lanfranc’s 2 truly ancient hospitals: St John’s for the poor and infirm, St Nicholas’ for lepers. Both well endowed but this did not mean in the difficult 14th century that both weren’t pleading poverty. Moreover, although neither were supposed to take in corrodians – provide money or property in exchange for a bed (as in the revised regulations of 1299), this did not stop the practice and various archbishops, as the hospital patron, send their retired servants and others to take up such places, albeit without the fee.

The third early surviving hospital is St Thomas’, the foundation of Edward FitzOdbold for poor pilgrims, which on its amalgamation with St Nicholas and St Katherine’s hospital in 1204, came under archiepiscopal patronage. Yet again the 14th century was a tricky time, but the revision of the rules in 1342 regularised matters and it continued. Not far away was Maynard’s hospital, its founder being Mayner the Rich, a wealthy citizen and borough reeve who established his hospital for 7 poor and infirm persons with a priest on a corner plot with the house next door. We know far less about its medieval history, but it survived!

The two other survivors are Manwood’s hospital, founded mid 1570s at Hackington just to the north-east of the city and named for its founder, Sir Roger Manwood, and therefore having parallels to the far earlier Maynard’s hospital. Other similarities to some medieval hospitals were the use of the parish church and the setting up as overseers of the hospital through their annual visitation officers from the city – the mayor and 2 aldermen, and from the church – the archdeacon of Canterbury, the local rector and churchwardens.

John Boys, the founder of Jesus hospital over 20 years later similarly used the term hospital for his charitable institution and the choice of ‘Jesus’ is interesting not least because of the use of such a dedication for some chantry colleges in the late Middle Ages, such colleges often had a school, as well as bedesmen. Such a choice possibly linked to the prevalence of the Jesus Mass and ideas about affective piety, part of late medieval devotion.

I’ll skip over the ‘casualties’ beyond listing them as the two leper hospitals of St James and St Lawrence, both of which outlived their mother houses but barely reached the 1550s before becoming gentry residences. The Poor Priests’ hospital, although that will feature later, was not surrendered to the Crown until 1575, while the maison-dieu type almshouses, including Pocock’s almhouse under the city wall near Holy Cross church and Swerder’s almshouse in St Peter’s Lane, were relatively short-lived houses. Yet, it is interesting to note that the idea crossed the Reformation divide, Thomas Batherste over fifty years later intending that Mother Cole should continue to live rent free in the dwelling she occupied for the remainder of her life.

To provide a comparison between the surviving hospitals at the beginning and end of the 16th century, we looked at these two periods in turn, and for the purposes here I’ll stick to the St John’s evidence. For the early Tudor period, the features are: a degree of expectation that new brothers or sisters (or their sponsor) would provide an entry fee and the going rate seems to have been around 35s, suggesting that we are looking at poorer people, not the poor. At the same time, the archbishop’s corrodians were continuing to find places at the hospital. There seems to have been an increased emphasis on the brothers/sisters’ devotional activities – attending church daily, saying prayers such as the Pater Noster and Ave Maria numerous times and praying for the souls of the hospital’s benefactors. Even though the chantry at St John’s hospital chapel (in the Lady Chapel) may never have come to fruition, this was John Roper’s intention.

Yet at the same time there was a move away from communal living as hospital brothers/sisters gained their own dwelling, which some sought to enhance: Thomas Consaunt intended his executors would see to the building of a new kitchen at his house there and Margaret Fryer provided 10s towards a new chimney in her own hall. This throws up another factor, that often the husband seems to have entered the hospital first, going back to Thomas again, his wife seemingly took on his house after he died, and in Thomas’ still new kitchen she had a great iron spit, her brass pots, kettles and pans, and elsewhere in the dwelling was a bed, at least one table, several candlesticks, a chest with a spring lock, pewterware, silver spoons and her clothing. Such a move away from communal living extended to working, and Alice presumably worked in her house carding lambs’ wool – her will mentions such wool, cards and her wool basket.

Nevertheless, the concept of the hospital community was not dead for as well as church services, communal feasting on such occasions as the patronal festival, the funeral of brothers and sisters, and at the annual reading of the statutes took place. Although not of St John’s John Whytlok wanted to be remembered there and at St Nicholas’ through the inclusion of his name in their bederolls, thereby receiving the prayers of the inmates, while Joan Bakke intended that for 3 years the anniversary of her death (obits) would be celebrated as they would for a deceased sister, seemingly feasting on bread, cheese and ale. This bringing together of the community of the dead and the living remained a major factor.

One of the reasons we know about these brothers and sisters at St John’s hospital is the number of such surviving wills, and although there are gaps in coverage over the century, there are enough from the early decades and the late decades to demonstrate that throughout the Tudor period the concept of having and retaining one’s possessions, rather than these passing to the hospital, was a constant. For example, Andrew More bequeathed his cupboard, table, 4 joined stools, 2 chests and 3 painted clothes that had presumably hung on the wall of his dwelling in his will.

Another characteristic from both ends of the century was husbands entering first, and sisters were generally widows or single women. Anthony Allen intended that after his death his wife Alice would move into St John’s and have all the stuff in his house there. His son was to deliver to her each year 12 bushels of wheat (for bread) and 12 bushels of malt (beer/ale), while her 3 pigs, which were with the son, were to be delivered to her at ‘killing time’. Whether the 2 geese, 1 gander, 4 hens and 1 cock joined her at the hospital isn’t clear, but his 3 swarms of bees were to go to St John’s, 2 for the hospital and the 3rd for Alice.

Even though the form of the services at the hospital chapel had changed, the regulation that the brothers and sisters must attend had not. Archbishop Parker stipulated that they should attend morning and evening prayer, know certain prayers, the catechism and other articles of faith and attend sermons each Sunday at the ‘sermon house’ (the old chapter house at the cathedral). Nor were they to go beyond the hospital without permission, but in reality, the ability to retain contacts outside St John’s does not appear to have diminished between the early and late period, and when Magdalene Colbrand made her will in 1579, she was awaiting judgement in a case she had in the bishop of Rochester’s court at Rochester concerning goods valued at £18.

However, at one Canterbury hospital the inmates had changed markedly for following the destruction of Becket’s shrine, St Thomas’ hospital lost its meaning and it fell into decay and was almost lost. Rescued for the first time by Archbishop Parker in the 1560s, he might be said to have kept the spirit in some ways of the old pilgrim hospital in that the 12 beds were now for the wandering poor with an elderly woman again retained to care for them. Out relief given weekly at the hospital gate was similarly reinstated, but an innovation was a school for 20 boys in the chapel, although it is feasible the chantry priest in the early 16th-century had offered schooling in some form. However, this form of the hospital did not last and once again Eastbridge (St Thomas’) hospital fell into ruin until rescued by Archbishop Whitgift who, in 1586, established an almshouse for 10 in-brothers and sisters and a similar number of out dwellers. Selection criteria were now 7-year local residency, being elderly and impotent ie they were unable through age or ill health to be productive member of the commonweal and so were members of the worthy poor. Their presence at morning and evening prayer was also required, as was attendance on Sunday and holy days at the sermon house. The school, too, was reinstated, the poor scholars expected to become useful members of society, albeit there were 2 scholarships to Cambridge for the most able, the intention being that they would become clergymen, something pre-Reformation hospital benefactors would also have endorsed.

But what about Maynard’s hospital and the Poor Priests’ hospital? These in the later 16th century came under Canterbury’s civic authorities, Maynard’s as a small almshouse in terms of numbers accommodated, in other ways was probably similar to St John’s and St Nicholas’, but it is the Poor Priests’ that witnessed a radical reuse. Having humbly petitioned the Crown to have the hospital and its possessions, the city authorities converted it to Canterbury’s second attempt at a Bridewell or house of correction, for here were to be incarcerated and set to work those seen as ‘sturdy beggars’, ‘idle poor’, ‘vagrants’, ‘masterless men’, who collectively were known as those who ‘lived evilly’. To a degree such ideas were applied similarly to 20 poor boys, who were to be educated sufficiently so that they could be apprenticed and thus become useful workers in society. Yet even though the term Bridewell was new, the fear of beggars and vagrants was not, and it is worth noting that hospitals had been used in previous periods as places to hold those seen as undesirable, and at times of economic or social difficulty, such measures were and would again be more draconian.

Finally, we explored what life would have been like for the inmates at Manwood’s and Jesus hospitals and how different or not they would have been compared to the lives of those in the late medieval well-endowed almshouses. I’m not going to go into detail here but suffice to say, as with St John’s hospital at the beginning and end of the Tudor period, there might be said to be considerable continuity in terms of everyday life, albeit there was the change from Catholic to Protestant religious observances.

However, what I do want to highlight as a final point is that taking Manwood as my example, he and his hospital offer a great case study of appropriating the ‘old’ to establish the ‘new’ when setting my first 2 images up against Manwood’s funeral monument and its position within the southern transept of St Stephen’s church. The elements I focused on were: his transi-tomb built during his lifetime; the special and temporal dynamics of the distribution of bread to his almsfolk on Wednesdays and Sundays after morning prayer; their presence in this church – the living embodiment of his charity as honest almsfolk; the weekly dinner on Sunday after morning service at Manwood’s house; the annual sermon which they attended; and that every 3rd year they received clothing and shoes of St Andrew’s feast day. So like Thomas Arden (1567) ‘a good work maketh not a good man, but a good man maketh a good work, but for the recipients, as for Roger Manwood compared to his grandfather, things had changed but much would have been familiar to the older Roger, the ‘godly poor’ or the ‘God-fearing poor’ fulfilling their side of the reciprocal relationship with their benefactor through their religious observances, gratitude and sober behaviour.

When I finished, there was a host of questions for members of the enthusiastic audience. Moreover, Helen Nattrass the Society’s secretary, had very kindly invited me to the lunch afterwards and this provided an opportunity for further discussion about the lives of these brothers and sisters in late medieval and Tudor Canterbury, as well as other interesting topics. Consequently, I would like to thank the Society for the chance to talk about these fascinating charitable institutions which still function for those living in them today in ways their Tudor predecessors would have understood. For example, as one member of the audience pointed out, the concept of the husband entering first, his dwelling at St John’s taken on by his wife after his death has just happened again recently. And next week I’ll be crossing to Faversham to give you a report following Jason’s presentation to the Kent History Postgraduates group.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 4298

4298