Progress on the Tudors and Stuarts History Weekend website continues but is not quite finished. Consequently, this week I am going to concentrate on a fascinating lecture I heard last night by Keith Parfitt of Canterbury Archaeological Trust. This was part of the autumn programme organised by the Friends of the Trust, the Centre’s partner for the Early Medieval Kent conference last Saturday, and featured the archaeological excavation Keith led recently in the St James’ area of Dover. However before I get on to that I will just mention that I received a very warm welcome at Lympne on Tuesday where I was giving a talk on the medieval hospitals of the Cinque Ports with special reference to Hythe. The Hythe hospitals are particularly interesting and I have not yet totally untangled quite what happened in the second quarter of the fourteenth century regarding Bishop Hamo of Rochester’s two hospital charters. Also worth mentioning, Dr Claire Bartram gave a lecture last night at the Kent History & Library Centre at Maidstone on Elizabethan book culture in Kent. And as a final reminder, it will be the Nightingale Memorial Lecture next Wednesday at 7pm in Old Sessions on the University’s Canterbury campus on ‘Wartime Farm Revisited’ by Professor John Martin of De Montfort University – all welcome.

To return to the Dover dig, the potential area of the site comprised about a fifth of the walled town, albeit when the excavation began Keith and his team were quite restricted in terms of the areas they were allowed to work on and for how long. Such restrictions are immensely frustrating, especially because Keith had been keeping his eye on the site ever since 1996 when he dug the BP filling station site nearby. That site, known as the Townwall Street excavation had uncovered a wealth of detail about the town’s fishing community in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and Keith expected his new excavation would reveal similar features, such as vast quantities of fish bones, pottery and fishing equipment, and poorer housing stock with a succession of chalk floors. In part this was the case, but the four sites revealed other details about the town’s development too.

For those who know the town, the site is to the east of the River Dour and bounded by St James Street, Clarence Street and Dolphin Lane. Today the Dour is a very insignificant river, but in Roman times the estuary was large, and probably included a harbour where a squadron of the Roman navy had a base. A nineteenth-century gasometer nearby apparently sat on site of part of the Roman harbour wall. Although Keith is still working on this aspect of the area’s topography, he is coming to the conclusion that this structure may accidentally have been instrumental to a degree in the silting up of the harbour in the St James’ area – marine sand building up to the seaward side, marshland to the rear or inland side. More boreholes are required to gain a better idea of the development of this crucial area and thus the town as a whole, but at the moment this does not appear to be possible.

Leaving aside further consideration of the Roman history of the site, it seems worthwhile to move on to the medieval period and as well as the sequences of chalk floors mentioned already, the site also produced what looks to be the undercroft of a substantial fifteenth-century stone building. The stone is local, the wall being mortared greensand boulders and within there was a pit that cut into the corner in which was a skeleton of a newborn child. Although there are a number of potential explanations, including the possibility that the child died before s/he could be baptised and thus would not have been buried within consecrated ground, the practice remains somewhat of a mystery.

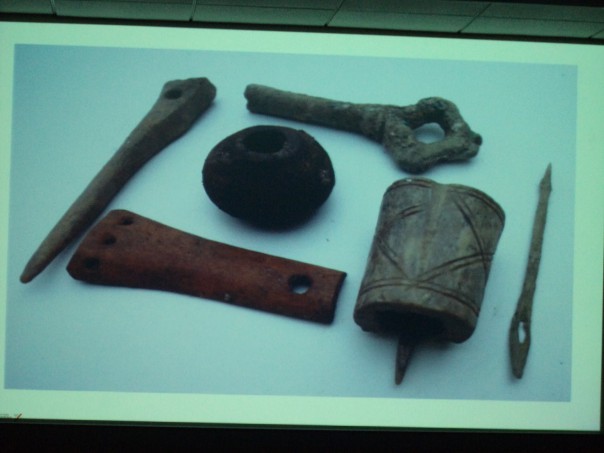

Another interesting local practice concerns the number of cat bones found in a cess pit. The bones show signs of butchery and at the moment Keith’s idea is that for some reason these animals were to be skinned to provide fur, although what was special about cat fur I do not know. Keeping to this idea of artefacts, I thought you might be interested in a few pieces found at the site. These include a needle for mending fishing nets and a decorated bone piece for French knitting. One thing I did not know was that slate may denote a West Country source and that such materials had been in use since the thirteenth century.

Although this has been a whistle-stop tour through the Dover excavation, I hope that you have at least gained a flavour of just how important it is in the uncovering of the development of the town from Roman times until the present day. For this area at the foot of St James’ church is the meat in the sandwich between the ‘old town’ to the west and the castle to the east, and even though for several centuries it may primarily have been marshy ground before becoming fully habitable, its strategic importance is clear. Hopefully, this excavation will form the central part of a new book on the town, and it is such work that will provide scholars and the interested reader with a better understanding of how Dover and Kent developed over the centuries. For as Keith said, unlike Canterbury where the Trust is developing a new project on ‘XX Centuries of Canterbury’, this is not feasible for Dover, yet it will still be possible to gain a clearer understanding of this vitally important town, as important today as it has been over the centuries since the Bronze Age.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 770

770