I hope our regular (and all) CKHH blog readers had a good Easter Weekend. My thanks to Dr Diane Heath who this week has been busy putting the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2024 souvenir brochure together so that it can go off to be printed. And for this week I’m going to mention four talks coming up next week and then the one I gave to Lenham Local History Society on Maundy Thursday evening.

To next week, firstly Dr David Shaw (Hon. Research Fellow in History, University of Kent) on Monday 8 April will be speaking on ‘Researching the administration of the Poor Law in the eighteenth century’ at 1pm. This will be at the Kent History and Library Centre at Maidstone as one of their lunchtime lectures. The talk is free, but you need to book a place by either calling 03000 420673 or emailing archives@kent.gov.uk and Dr Mark Bateson at KHLC will be delighted to see you.

Then on Wednesday 10 April at 7pm Mansell Jagger will be giving the April CHAS lecture at St Paul’s church, Canterbury on ‘When Kent said ‘No’ to Napoleon, 1804 and Invasion of England’. Visitors welcome and £3 on the door to non-CHAS members.

Thursday 11 April at 7.30pm in Sandwich Guildhall, Dr John Bulaitis (Senior Lecturer in Modern History at Canterbury Christ Church University) will give a lecture on ”The respectable fascist’ – George Christopher Solley, Mayor of Sandwich (1919-21)’ to Sandwich Local History Society. Everyone is welcome to this lecture and many of you will know, John’s new book on tithe disputes in England and Wales will be published this summer with Boydell.

Finally in Canterbury at the Cathedral Lodge, on Saturday 13 April for the Canterbury Gregorian Music Society, I’ll be giving a talk on ‘Canterbury’s Hospitals and Almshouses in Medieval and Tudor Times’. This follows the Society’s short AGM, begins at 11am and is open to those interested in the city’s past. Tickets can be purchased through: https://www.ticketsource.co.uk/cgms and includes refreshments before the talk.

Now going back to last week and the visit to Lenham to talk to the lovely, keen local history group who are undertaking various history projects on their community’s history led by their very active committee. For Maundy Thursday I was talking on ‘Going to Church in Medieval Kent’ with the idea of using Lenham examples, as well as from other parishes in the county. To provide a context, I started by exploring briefly the Church as institution in Kent from its beginnings in terms of Roman Christianity following the arrival of Augustine in 597 and that the impetus may have come as much from Ethelbert and Bertha through their Merovingian links as from the idea of Pope Gregory’s mission to the English. For this impetus had led to the primacy of Canterbury, as well as a second diocese at Rochester, and the spread of dual religious houses and minster churches, as well as their associated daughter churches.

This took me on to the church as parish church within the diocesan structures of Canterbury and Rochester and that compared to some dioceses, these churches were more likely to have been established and therefore be under the patronage of ecclesiastical institutions – the archbishop/bishop, various religious houses, than under royal or aristocratic patrons. Moreover, this network of parishes had been created by the mid 12th century, the parish forming a religious, but also a social territorial unit in the landscape, the responsibilities of the parishioners developing and solidifying over time.

This took us to thinking about why religion mattered – as the cement that held medieval society together under the simple three-fold reciprocal system of those who fight, those who pray and those who work. Additionally, we explored how medieval people understood the importance of saving the soul through the ideas of the Venerable Bede and the frequent depiction of the Last Judgment, often above the chancel arch with Christ judging the living and the dead, the division of the sheep and the goats and the emphasis placed on the seven corporal works of mercy. Taking this a stage further, we considered medieval religious worship as both an individual and a communal response, which took us to the church as building – a space rich in Christian symbolism as understood through the four-fold system (literal, allegorical, moral and of higher things) where everything could enhance the believers’ piety and understanding.

I took a little bit of time to discuss the role of the churchwardens as the elected representatives of the parishioners and thus which parts of the church building, its fixtures and furnishings came under their remit – an extensive list. For in addition to much of the building – the nave, church tower and the churchyard, including the fencing, the parish was expected to supply items including the liturgical books, all the images, chalices, vestments, the font with a cover, lock and key, bells with ropes, a bier for the corpse at funerals, a set of banners, a processional cross, altar frontals and cloths, and much, much more. Nevertheless, as inventories drawn up by churchwardens show, many churches far exceeded the basic requirement and these and other records show the presence by the 15th century of pews, in Herne church by the 1460s, and organs, such as Thomas Burges of Lenham who bequeathed 8d towards the buying of a new pair of organs in 1518.

The next topic was who, when and how people attended church. While all were expected to attend their parish church every Sunday, there was some allowance for those looking after livestock, away fishing, working as servants, millers watching to catch the wind or travelling as merchants, plus the elderly and infirm, but complaints about persistent offenders might see them before the church courts with the likely penance of holding a candle at the mass time to be given as an offering or being beaten around the church. An interesting concept linked to such non-attendance was St Sunday, found at several Kent churches including Lenham, Leeds and Ospringe, where the image of a bleeding Christ was shown surrounded by contemporary instruments and items used in leisure and work on a Sunday that wounded him. These might include spades, scythes, dice and musical instruments.

The principal mass was held at 8am or 9am, and all were expected to have fasted before this, but on workdays some churches celebrated an earlier mass, the morrow mass at daybreak. As well as Sundays, there were a number of chief festivals such as those linked to Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, the church’s own patronal saint and the offering of Peter’s Pence, to be done by 1 August, and together these comprised between 27 and 36 days in addition to Sundays. Having fasted beforehand, all by the age of puberty were expected to receive communion (housel) on Easter Sunday in the form of the bread alone (through transubstantiation Christ’s body), having been to confession, preferably on Good Friday. The day then becoming one of celebration.

Having set what might be seen as the parameters of medieval churchgoing, we explored in a bit more detail the liturgical year, following the life, passion and resurrection of Christ from Advent through to Ascension Day, with the associated feast days of Pentecost, Trinity Sunday and Corpus Christi. Nor, as we had already noted was this the sum total because there were the feast days of the Virgin Mary, especially important at Lenham, for example, as they were at many Kentish churches because of the patronal dedication. And as a final touch, I briefly mentioned the seven great processions that took place at least in part outside the church building, always conducted in a clockwise direction. The Palm Sunday procession at Lenham after 1471 presumably making use of the new palm cross that Thomas Horne had bequeathed 20s towards in his will.

Of course, the parish church was the site (and sight) of life-cycle events, from baptism at the font, located near the west door or one of the nave side (north/south) doors, through to the funeral and burial, which for most would have been in the churchyard, by way of churching (for mothers after childbirth), confirmation and marriage. As these might be seen as a pilgrimage through life, I added pilgrimage into this section, and while some went on pilgrimage during their lifetime, for others pilgrimage by proxy after death was an alternative. Keeping with Lenham, it is interesting to note that Katherine Lelysden (1519) bequeathed 4d to be taken to the Rood of Grace, with a further 4d to be given to ‘him that takes it’. However, she also looked much further afield, intending that a donation should be given to the wardens of the ‘Resurrexion in Caleys’, and at neighbouring Boulogne 4d was to go to a priest to sing mass before ‘Our Lady of Bullayne’, a cult centre that Chaucer’s Wife of Bath had apparently visited.

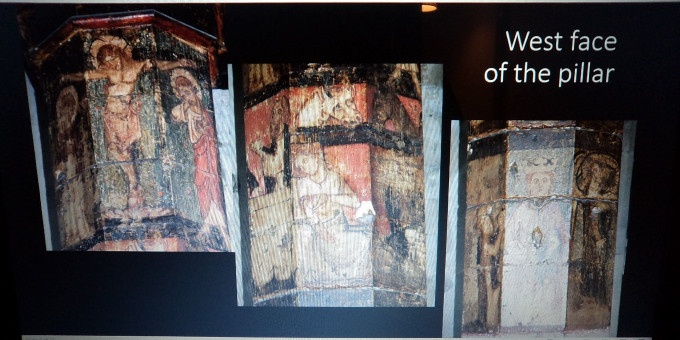

Returning to more parochial devotional issues, albeit also involving communal elements, we investigated the role of parish guilds, give-ales, drama and meeting places. For even though the wills do not always designate all the fraternities at a given parish, the need to ensure each locus for devotion with its image (in various forms) had sufficient lights or candles means that light stores required collective actions at the sub-parochial level. Such foci at Lenham included several in terms of the cult of Our Lady, such as the Assumption of Our Lady, Our Lady of Pity, Our Lady in the High Chancel, Our Lady of Grace and Our Lady of/in Gesyn (childbirth and thus the Nativity). The last of these is especially interesting and unusual, particularly in the knowledge of a similar focus at Faversham and that church’s wonderful painted pillar.

Similarly uncommon are references to give-ales, but as a means to raise funds for the parish church this is probably the paucity of records rather than their absence. For a couple of examples at Ivychurch on Romney Marsh there was a St Thomas give-ale to which Thomas Whatman of Old Romney bequeathed 3 ewes, while at Petham the St Margaret’s brotherhood and give-ale was to receive half a bushel of wheat and another half bushel of malt as requested by Thomas Austin in 1484.

Drama, too, was another way to raise funds, plays based on saints’ lives or biblical narratives, the REED volumes for the diocese of Canterbury containing numerous examples linked to both parishes and Kent’s many small towns, including the St George play at Lydd and the Passion play at New Romney. Furthermore, John Weston, at Lynsted in 1482, directed that certain land within Church field could be used by the parishioners as the ‘Playing Place on holy days’. Although for a different purpose, the idea of the area around the church being for parish use was mirrored by Thomas Duffyn the vicar at Lyminge because in his will of 1508 he left £4 towards building a place in the churchyard where parishioners at obits and other commemorative times might hold their drinkings.

The last section before the Reformation gave us a chance to think about the church as a place for civic elections, as took place at the Cinque Ports, where schooling took place including the teaching of pricksong and therefore the incidence of choirboys. This development had begun at cathedral and monastic Lady Chapels, and while such teachers might be chantry priests, it was the parish clerk at St Clement’s church in Sandwich. On the edge of what the church authorities would tolerate was the holding of fairs, and even though I haven’t found one in a Kentish parish churchyard, at Bristol an important fair was held in St James’ churchyard.

To finish off, I looked at Lenham c. 1540 as one of Archbishop Cranmer’s ‘troublesome towns’ as seen in the depositions collected on his behalf during the inquiry into the Prebendaries’ Plot against him. As these depositions show, even though many of Lenham parishioners seemingly kept their heads down, there were vocal supporters of traditional orthodoxy among the local clergy and parishioners who were opposed by an equally vocal of clergy and parishioners group who were looking for more and faster reform. Thus, we have the Reformation at a parish level as both top-down and bottom-up, but all sides were aware of the importance of the Church and church of which they were a part.

Thereafter there were several interesting questions, and I should like to thank the audience for the chance to share such a fascinating topic with them. If you would like to explore this subject further, I would recommend works by Eamon Duffy and Nicholas Orme.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1722

1722

Sheila, thank you very much for a very interesting and inspirational talk. Since the talk, we discovered a list of the ‘lights’ in St. Mary’s Lenham in ‘Testamenta Cantiana’. We have been looking for such a list for months! ‘Our Lady of Gesyn’ features in this list in 1473, 1475 and 1501. To our knowledge, Faversham and the north -south connection between the Weald and Faversham ( The ‘High Street’ being part of it) was in the medieval period more important than Maidstone and Ashford. The market in Lenham will have been a trading point for goods coming and going to the harbour in Faversham. In addition, the Manor of Lenham was in the hands of St. Augustine’s Abbey. There is still so much for us to learn!

Glad you found it useful Henny, and yes, there are good north-south links, also worth exploring which other churches had this fairly unusual devotion and its association with the holy family, as well as the role of the Jesus Mass in the devotional life of the parish.