This blog appears in the final week of Professor Louise Wilkinson’s time at Canterbury before she takes up her new appointment at the University of Lincoln. I, Diane Heath, am writing it instead of Sheila Sweetinburgh, but all of us at the Centre of Kent History and Heritage, and everyone (staff and students alike) in the School of Humanities at Canterbury Christ Church University shall miss her very much and wish her a wonderful time in Lincoln.

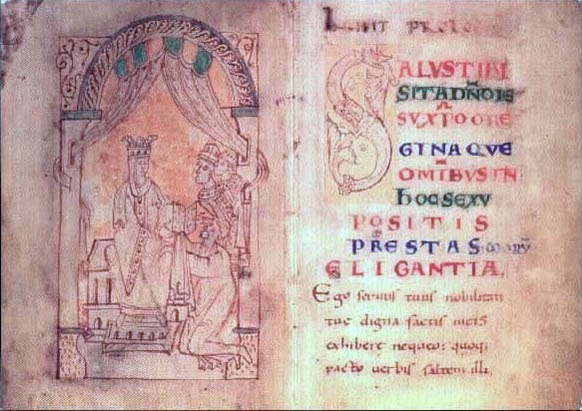

As Louise specialises in the study of medieval royal women and their children, and noble women and their families, it seems fitting to present an encomium for her – in praise for her time with us at Canterbury Christ Church University and for her work as co-Director of the Centre for Kent History and Heritage. A much earlier paean of praise, Encomium Emmae Reginae (pictured above), a famous eleventh-century manuscript, was written for (and also at the behest of) an equally famous queen, Emma, consort first to Aethelred II and then Cnut, and mother of Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor. The illustration on folio 1v of the manuscript (now London, British Library Additional MS 33241) is a well-known medieval image of female literary patronage, and perhaps this book was given by Queen Emma herself to St Augustine’s Abbey, in the grounds of which our university now stands. In the full-page miniature, Emma, wearing her crown and sitting beneath a curtained and beautiful Romanesque archway, receives her book from the kneeling monk-author (the ‘Encomiast’) while her two sons look on. The open curtains may remind the modern reader of a scene from a play, a ‘ta-da’ tableau of book gift-giving, so much better than an Amazon voucher.

Of course, there are some not-so-subtle differences between Emma’s Encomium and this blog post on Louise. Louise has, naturally, not sought her own encomium, and this blog is not the fake news compilation that makes up Emma’s book. If that seems too harsh and too modern a term for an eleventh-century text, bear in mind that the book has been called an early form of fiction. Furthermore, a previously unknown version was found in 2008 (now in the Danish Royal Library) with a later re-worked ending by the same author that presents a very different spin from the rest of the book, by praising Edward the Confessor. That such a revision was required amply demonstrates Emma lived in interesting times. Nevertheless, let us in an amicable spirit concentrate on how the Encomiast called Emma ‘the most admirable of her sex’ and someone whose ‘excellence transcends the skill of anyone speaking about’ her, descriptions which readily apply to Louise.

When I first met Louise in 2012, she had already been at Canterbury Christ Church University for eight years. I took on some of her teaching for second year students, as well as convening a new course on Religion and Society 1300-1600. Louise was a model teacher and lent me her time, kindest advice, and even her books. Indeed, I used one of her books so extensively I had to buy a new copy to replace her volume. My books often bear heavy annotations, broken spines, post-it notes, turned-down corners and coffee stains; in contrast, Louise’s books are all immaculate, preserved in clear book covers, and easily found on her well-ordered shelves. Moreover, her office is an oasis of calmness and efficiency, with comfortable chairs for her guests, and a lovely view of Canterbury Cathedral from her window, a sort of medievalist bibliophile’s paradise. I hope the view from her new Lincoln office window is as good.

While Louise’s work on the Pipe Rolls of Henry III and on Magna Carta is of great renown, her study of medieval women’s history is perhaps closest to her heart. As well as being the author of numerous articles on the topic and books including, Eleanor de Montfort: a Rebel Countess in Medieval England, and co-editing the Routledge Queens of England series, Louise also has in-depth expertise in medieval Lincolnshire’s women’s history, from alewives to Lady Nicolaa de la Haye, who was keeper and stalwart defender of Lincoln Castle at the time of King John. I recall last year students at the Royal Harbour Academy at an outreach workshop being totally amazed to learn how Nicolaa was in charge of her own castle and saved England from the French. Indeed, Louise’s work on medieval women’s lives has opened up gender history making it more accessible and emphasising its importance; women’s and children’s lives are just as interesting and worth further study as those of men.

Louise had asked me to give a paper for our Research Seminar this week but sadly coronavirus has led to the series being cancelled. Accordingly, it seems appropriate to give a shortened form of that research paper because it developed from a final year workshop I held in Canterbury Cathedral Crypt with Heather Newton for Louise’s course on Love, Sex and Marriage: sources for medieval women. Our terrific students gathered in the crypt to examine the tomb in detail and then explored some of the primary sources relating to the woman who ordered its design and placement.

The tomb with its battered alabaster effigy once housed the mortal remains of Joan de Mohun, a Lady of the Order of the Garter, who died in 1404. This canopied tomb is 240 cm high, 215 cm long and 85 cm wide and stands on a chamfered plinth. Red and blue paint traces on the vault of the canopy and on the base of the tomb indicate the original painting scheme, although the outer canopy is missing; Joan’s effigy has had the face obliterated, the arms and hands (probably in prayer) broken off, numerous graffiti carved into the body – even the dog at her feet has lost its head, Now only her tomb’s significant position impinging into the chapel’s altar space, the inscription, and her effigy’s hairstyle and clothing are left to express her piety and her patronal and noble status. Placed near (but not quite in) one of the holiest spaces within Canterbury Cathedral (the Undercroft Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary), Joan also lay almost (but again not quite) directly beneath the shrine of Thomas Becket. This location invested her resting place with a double sacrality and a double liminality. How did a medieval woman succeed in gaining such unprecedented close (if not quite unalloyed) access to this sacrosanct male monastic space – previously reserved for the monastery’s priors and its archbishops? Why was the placing and spatial location of her resting place of such importance to Joan that she paid for a perpetual chantry so far from her predeceased husband’s burial place at Bruton in Somerset? Let’s also note that besides not being buried with her husband, Joan de Mohun did not commission a sweet hand-holding paired effigy depicting medieval marital bliss – such as the famous Arundel tomb Larkin saw as epitomising ‘what will survive of us is love.’ What does an examination of Joan’s tomb and its location add to our understanding of late medieval female elite religious and familial piety? What was being memorialized here – family, lineage, or a more personal and politicized salvation mission statement?

Lady Joan de Mohun, née Burghersh, was a wealthy noblewoman of Kent, who married her uncle’s ward, Sir John de Mohun of Dunster, Somerset in around 1341. The couple had three surviving daughters: Elizabeth (later countess of Salisbury, an excellent match); Matilda (d. 1397), who married John, Lord Strange of Knockin; and Philippa, who married three times, last and most splendidly of all to Edward, Duke of York, grandson of Edward III. Both Joan’s brother Bartholomew and her husband John were original members of the Order of the Garter, Joan wore Garter robes too besides being lady-in-waiting to both of Richard II’s queens, Anne of Bohemia and Isabella, his French child-bride. Joan was also closely connected to John of Gaunt and brought up his daughter Philippa (the future queen of Portugal) in her household. Joan was an eminent Ricardian courtier, who made spectacular marriages for her daughters and sold her late husband’s castle to pay his debts, effectively depriving her daughters of their patrimonial inheritance. Joan retired in her last years to the luxury of Canterbury Cathedral’s guest house, Meister Omers. Her will stipulated her bed hangings there were to be fashioned into vestment for priests saying masses for her soul.

What are the connections between the materiality of Joan’s painted alabaster tomb, its undercroft location, its chantry accoutrements, and her deathbed at Meister Omers? The extant documentary and literary evidence establish both the stability and the frailty of the interconnected and gendered networks of confraternity, court, and female chivalry of Lady de Mohun and the continuities and breaks of her tomb from its glorious inception to its current brutal disfigurement. Joan’s effigy’s stony gaze once alit upon the celestial vision of the Chapel’s Blessed Virgin Mary statue, before which the mass was celebrated beneath the Marian chapel’s scarlet-painted heavenly ceiling twinkling with golden mirrored stars. This focus on the eternal cosmos was expressed in Ricardian court culture, for example in Chaucer’s Treatise on the Astrolabe and such themes are also found in the slightly later beautiful Christine de Pizan poem Le chemin de long estude. Literary evidence explored in Jocelyn Wogan Browne’s reading of the extant opening fragment of the Mohun Chronicle discussed Albina the original founder of Britain (ultimately derived from Brut) and medieval female agency by exploring references to Ladies of the Garter in the Catalan epic, Tirant lo Blanc. This exploration of the lifecycle of Joan’s great stone tomb which suffered neglect, defacement and then a twentieth-century re-insistence of its beauty in the Second World War photographs of Bill Brandt. Joan’s effigy was a boundary-stepping, death-eating scopic object which epitomised the wealth, devotion, decadence, and decay of ‘Johane Burwaschs que fut Dame de Mohun.’ This brief analysis of Joan’s tomb might serve to make women previously considered ‘invisible’ or ‘inaudible’ prominent in their own tombscapes again, by adding ideas of female agency from Pizan, the Mohun Chronicle and Tirant lo Blanc, as well as records of Joan’s carefully chosen benefactions, the site and design of her own tomb, and her life as a distinguished courtier and member of the inner circle at court before and after her husband’s death. Joan’s tomb, effigy, and the architectural context of her lay patronage make this an important funerary monument.

Letting medieval women speak for themselves rather than considered only as patrilinear mouthpieces is a vital aspect of Louise’s work and we hope for great things at Lincoln. Please accept our very best wishes for your continued happiness and success, and we hope too that you like the gift that is being presented to you by your colleagues, a beautiful rainbow of hope in troubled times.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1837

1837