I’m going to start this week with some news. Many of you will know Paul Bennett or have read about him in various blogs over the last couple of years, and will know, therefore, that he is the Director of Canterbury Archaeological Trust and also a Visiting Professor in the Centre for Kent History and Heritage, Canterbury Christ Church University.

You will also know that Paul is passionate about archaeology and history, whether it is in Britain, especially Kent, Libya or Iraq and his contribution to the study in all these countries is massive, and he himself is legendary for his tireless enthusiasm. Consequently, it is totally fitting that his contribution to archaeology has been recognised and it gives me great please to record that he is in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list: Dr Paul Bennett MBE.

Dr Paul Bennett MBE (photo: Canterbury Archaeological Trust).

This last weekend also saw a couple of conferences. The Medieval and Early Modern Studies postgraduate students at the University of Kent held their third annual Festival on Friday and Saturday, and among the speakers were Abby Armstrong, a doctoral history postgraduate student under Professor Louise Wilkinson at CCCU, and me. Then on Saturday, the Centre held its ‘Tithe through the Ages: the Historian’s View’ conference. Unfortunately, I had to leave after my session at Kent University and was unable to hear Abby’s paper because I needed to check the AV system at Canterbury Christ Church with Terry from IT Services, but I will give you an idea of Abby’s paper from her abstract in the programme handbook.

‘Pregnancy in the Middle Ages was a highly regimented and ritualised process, especially for a queen. It involved a period of lying-in before the birth and was followed by the mother’s purification and re-entry into the church following a period of prayer and cleansing. These ceremonies are sparsely illustrated in the records for most of the medieval period. However, it is possible to piece together these childbearing rituals by using a variety of sources.

This paper explores the childbearing of Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III and queen of England, to further elucidate our understanding of these processes in the thirteenth century. Eleanor proves an excellent case study as she gave birth to five children: two boys and three girls. All of these births were recorded in the contemporary chronicles, revealing much about the concerns for Eleanor’s fertility before the birth of her first child, as well as the reasons behind the choice of names given to each child. Additionally, as Henry III welcomed all of his children into the world with much rejoicing and gift-giving, the chancery records also contain various details concerning the births of Eleanor’s children.

Furthermore, the entire process of childbearing and subsequent purification emphasised the otherness of a woman, in her fertility and ability to bear children, but also provided an opportunity to celebrate these exceptional female roles. Therefore, this paper demonstrates how the queen’s otherness was expounded and celebrated by her childbearing and purification rituals, through the examination of Eleanor of Provence.’

Another of Louise Wilkinson’s doctoral students Harriet Kersey was at Abby’s session and reported that the audience had greatly appreciated Abby’s paper and that the whole session had been very good. She had also enjoyed a couple of the afternoon workshops. Firstly, Dr Marianne Wilson (The National Archives) had brought facsimile documents from Kew from the time of the Dissolution, which they investigated, and then Harriet was part of a group that explored early modern materials from Kent’s Special Collections and Archives, under the guidance of Karen Brayshaw and her colleagues, including the 1586 edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles.

Elizabeth Finn discusses Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s ‘The Payment of Tithes’, c.1620.

Turning now to the Tithe conference, Mary-jane Pamphilon, at the Reception Desk, welcomed attendees as they arrived and then almost 70 people took their seats in the Michael Berry Lecture Theatre in Old Sessions House to hear Elizabeth Finn, an archivist at the Kent History and Library Centre, introduced her audience to the tithe system from medieval to modern times. This first session was extremely useful for audience members because tithes are one of those taxes that people often think they know about until they actually come to think about it properly. Elizabeth very gently and imaginatively took her audience through from Anglo-Saxon times to the final abolition of tithes in all guises in the late 20th century. She provided useful definitions, including what were the different sorts of tithe: predial – all things arising from the ground and subject to annual increase, for example, grain, wood, vegetables; mixed – all things nourished by the ground, for example, animal produce such as milk, eggs and wool, and the young of cattle or sheep; personal – a tax on labour (wages), particularly the profits from mills and fishing, and on rents. She also talked about how what was subject to tithe changed over time and gave the example of hops that was introduced in the 16th century and became extremely lucrative as a source of tithe for many clergymen and tithe farmers thereafter, especially in counties such as Kent.

She also discussed exactly who was able to collect tithes and why this tax had been introduced in the first place to provide an income for the incumbent, to provide funds for the upkeep of the church building and to help the poor of the parish. Elizabeth also considered how this apparently simple relationship became more complex when the tithes were appropriated by religious houses who then had to find a priest to serve the parish. The vicar was allowed to keep certain tithes and the remainder went to the religious house. As Elizabeth explain, the Dissolution brought an end to such monastic appropriation, but often lay farmers bought out these continuingly lucrative taxes from the Crown – called impropriation. This led, as it had done during the Middle Ages to resentment among the tithe payers, especially at particular times of hardship or economic depression. Furthermore, the rise of non-conformity in the 17th century fuelled even more resentment and resistance, archbishops such as Bancroft and Laud responding by seeking to enforce the tithe system. Later in the century the Quakers, too, found themselves in a ‘battle’ over tithe, their privations recorded in Quaker Suffering Books, while about a century later tithes in terms of the fate of the Tithe Pig appears to have become the rallying call for those seeking to resist such payment. This took the form of songs, satirical cartoons and ceramic groups, and I think the tithe pig has the potential to provide a brilliant bridge between rural and urban tithe, and to offer a window into the social history of Georgian England (apologies for the mixed metaphors and worth mentioning that Elizabeth also managed to sell numerous copies in the Kent History Project series).

Boitard’s engraving of the ‘Tithe Pig’ [http://www.mystaffordshirefigures.com/blog/the-tithe-pig].

Taking her audience into the 19th century, Elizabeth explored the 1836 Act of the Commutation of Tithes, applicable only in England and Wales, where the government decided to commute tithes, that is to substitute money payments for payments in kind. These new corn rents, known as tithe rentcharges, were not subject to local variation, but varied according to the price of corn calculated on a septennial average for the whole country. For the historian, this Act has provided some wonderful resources and tithe maps, at a scale of 25 inches to the mile, were produced with apportionments, that is tables showing land owners and occupiers, the number, acreage, name or description, and state of cultivation of each tithe area, the amount of rentcharge payable, and the name(s) of the tithe owner(s). However, as Elizabeth discussed, these materials are great for historians but didn’t stop the feelings of resentment at the time. These again rose to the surface late in the century and again in the 1930s, in other words during times of agrarian crisis. She noted that such matters are still sensitive and that some records held by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners are still embargoed. Nevertheless, tithe no longer exists in any form but it only finally ended just over twenty years ago!

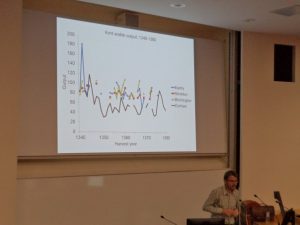

After refreshments, the audience eagerly awaited the medieval session comprising talks by Dr Ben Dodds of Durham University and Professor Christopher Dyer (University of Leicester), ably chaired by Dr Paul Dalton (CCCU). Dr Dodds has worked extensively on the Durham Priory sources, especially the tithe records, as well as looking comparably at the few other tithe series survivors across the country, including a few for parts of Thanet and neighbouring Eastry. I missed the beginning of his lecture and when I joined the audience, he was discussing Prior John Wessington’s reorganisation of the house’s finances of which tithe was an extremely important component. As Ben commented, Wessington was keen to demonstrate that the decline in the priory’s finances was not down to his mismanagement, and, as with the 1836 Act, this has created an excellent series of records for the historian, in this case covering the extremely difficult times of the 14th century.

Dr Ben Dodds discusses peasant farming in Durham and Kent.

Unlike beadles’ roll or similar manorial financial records that primarily cover the farming activities on the demesne (home farm) of the manor, tithe records offer a way of examining the farming activities of the peasantry. Trying to gain an idea of what peasants were doing, let alone thinking, is generally amazingly difficult for the Middle Ages. Yet, as Ben explained, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie’s famous book Montaillou purports to give us such insights into late 13th/early 14th century peasant ideas as a consequence of the depositions taken in Languedoc as part of the official crackdown on the Cathars. Now, these suggest that the local peasants were far more concerned about religion than they were about being innovative farmers, and the picture painted in this and Ladurie’s other work is of a population trapped in the ‘great agrarian cycle’, that is output per person remained static and society was caught up in a series of crises, especially during the 14th century. Ben was keen to say Ladurie’s studies have provided fascinating insights into peasant mentalité. However, he wanted to test this against the Durham and Kent records to see whether there was any evidence of a rise in production levels per person, and, to cut a long story short, he has found such evidence, which appears to imply that the historian is observing a different mentalité among at least some sectors of the English peasantry.

Professor Dyer, although looking at the issues somewhat differently, in many ways provided some comparable findings that extended the ideas about peasant mentalité into the 15th century. This is important, as Professor Dyer stated, because peasant farming accounted for about 80% of the cultivated land in the country. Examining the Worcester Priory estates in the Severn valley, and using inventories and more frequently tithe records, Chris Dyer showed the audience the type of crops grown on demesne lands, as well as by peasant households. As he said, the priorities of these two groups differed, and this was equally true concerning the manors/peasants from open field champion country compared to their counterparts in forest areas. Although extrapolating to total sums using tithe has its difficulties, as Chris noted, it does provide some useful ideas, such as the peasants’ preference for dredge – a mix of barley and oats suitable for brewing. Wheat was also grown and that provided bread, while animal feed came from oats, peas and beans. Such a cropping regime meant the average peasant was geared more towards the market than is often thought. Livestock, too, was important, especially in woodland districts, and such pastoral characteristics influenced the cereal-cropping regime, as well as the balance between spring and autumn-sown crops. And, similarly to Ben’s findings, these tithe returns point towards the importance of individual peasant decision making and a desire to increase output.

Professor Christopher Dyer assess tithe on the Worcester Priory estates.

Regarding the relative significance of tithe between rural and urban communities, this tax was more important in the countryside. However, the ability of tithe collectors to tax urban garden production – apples, leeks, onions, garlic, peas and beans, in addition to livestock and honey provides valuable comparable data, while tithes on flax open up ideas about local cloth industries. Yet, it was Chris’ exploration of the priory’s estimation system of crop yields that was particularly fascinating. The idea that reeves and others were sufficiently skilled to be able to put a yield figure on a heap of sheaves just by measuring the size of the heap and looking at some sample ears of corn was truly amazing – more lost skills!

After a break for lunch, Dr Paula Simpson, from the Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge, spoke first in the early modern session on tithe disputes in the diocese of Canterbury during the 16th century. Using a series of case studies, she discussed such matters as where these disputes had taken place, the language used by the protagonists and the witnesses, and whether either side had sought to use go-betweens or adopted other strategies in their determination to resist or reclaim tithes. Paula noted the significance of the parish church, and how different spaces within it were employed by vicars or their parishioners, firstly the differentiation between chancel and nave, but also between the seats of the parish’s lay elite in the choir and the communion table. She considered how either side might engineer action and the presence of potential witnesses who might represent the community’s interest. Moreover, she looked at how houses and shops might be used, thereby bringing in ideas of what spaces mean, how they are charged politically. Even though many of her cases referred to tithes on crops, she did mention livestock – the tithe pig again, but in terms of something else I have worked on recently, she mentioned fish tithes. These involved the weirmen, but I was intrigued to hear that when it came to cod the vicar demanded every third fish, giving in exchange a 1d for the hook. If anyone knows more about this, I would be pleased to hear from them.

Unfortunately, Stuart Morrison, who is doing his doctorate at the University of Kent, was ill but having sent his paper and PowerPoint, I gave the audience Stuart’s findings regarding the battle over tithes in London during the later 1630s. He has looked in detail at several manuscripts in Lambeth Palace Library and from these he has concluded that in this protracted dispute between the city’s clergy and the Corporation of London, ‘the clergy were in an unfortunate position’ because ‘they encountered an opponent … that were very politically and legally competent.’ Indeed, ‘the corporation used all the experience they had to stall, avoid and irritate the clergy’s attempts to bring change’ to the amount charged. As a result ‘in studying the tithe disputes we gain a glimpse of the conflicting impulses of Church and State under Charles’s personal rule.’ Stuart’s paper on urban tithes, which were really closer to rates, was extremely interesting and provided a good counter-balance to Paula’s assessment of the still rural county of Kent in this period.

Dr John Bulaitis considers the tithe disputes in the 1880s.

Following the afternoon refreshment break, the audience eagerly awaited Dr John Bulaitis (CCCU), who discussed the period from the 1836 Act to the final death throes of tithe in the late 20th century. As John demonstrated, this Act was passed in response to contemporary troubles, including a rally of 3000 people on Barham Down two years earlier, but really did nothing to address the root grievances of the tithe payers. Consequently, more government legislation followed but had little effect, and when economic circumstances for the tenant farmers, in particular, deteriorated later in the century, the scene was set for a showdown. For the tithe payers, the formation of the Anti-Extraordinary Tithe Association, which comprised a large number of Kentish hop growers in the Weald and from north-west Kent, was a key event in 1880. Thereafter these groups, which seem to have contained members linked through marriage as well as locality and a common purpose, sought to disrupt events such as the sales of distrained stock belonging to those who refused to pay tithe. Such campaigns of civil disobedience used various weapons, including cartoons in the local press, rallies and speeches to these gatherings. Moreover, from 1882, the agricultural labourers joined forces with the anti-tithe lobby, and a further alliance came in 1885-6 when links were established between those in Kent and those from Wales. The Welshmen added further dimensions to this fight because they were predominantly Methodists, and they wished to raise nationalist issues.

On balance they scored some successes, as well as entering local folklore, but the post Great War period failed to realise any meaningful reforms, leading in the early 1930s to further actions, the farmers caught in yet another agricultural depression. The formation and activities of the National Tithepayers’ Association were central as matters escalated from lobbying to campaigning. The first targets were the auctioneers, who were expected by the county courts to sell off goods belonging to non-payers, and when the authorities tried a different tactic, using general dealers to take possession of the distrained goods and remove them from the farms, this too was fiercely resisted. Thus, in 1934, the authorities sufficiently admitted defeat to set up a Royal Commission to look at the issue of tithe. The subsequent legislation saw the state buying out the tithe owners, and the rump of this hated tax was given over to the Inland Revenue to collect for the next 60 years.

So ended a fascinating conference and the buzz that had been there all day continued as people either headed out of the lecture theatre or came down to ask John specific questions. In addition, the day was also successful because having covered costs, there will be a small surplus to add to the Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award fund. It is possible, Andrew Leach (a CCCU 3rd-year student who was on hand all day to help the organisers) may be one of the recipients in the next round of awards because he is hoping to start an MA by research on a medieval history topic in the autumn that will include the study of Kentish lesser noble families. I wish him well with that and hopefully on his return to Christ Church he will get involved in Centre events once more.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1418

1418