Another busy week but I thought I would start with the Tudors and Stuarts History Weekend 2021 to say the web site has gone live for bookings, and Matthew will set it up more fully early in January. Please do check it out because we have great speakers and fascinating topics: canterbury.ac.uk/tudors-stuarts

This week I have three events to fit in which means each will have to be shorter than sometimes (it didn’t quite work out that way!!). However, before that I want to mention the 3 speakers from CAMEMS/Kent who will be joining the 3 speakers from CKHH/Humanities I featured last week as part of the Lunch Time Lectures starting on 13 January with the Friends of Canterbury Cathedral. These CAMEMS/Kent postgraduates are in order of speaking Dr Daniella Gonzalez, Cassandra Harrington and Anna-Nadine Pike; and in the preceding weekly blog I’ll give you the title, a short piece on the speaker, and the joining url for the lecture. So please do look out for these because I think we will be in for a great treat in January and February.

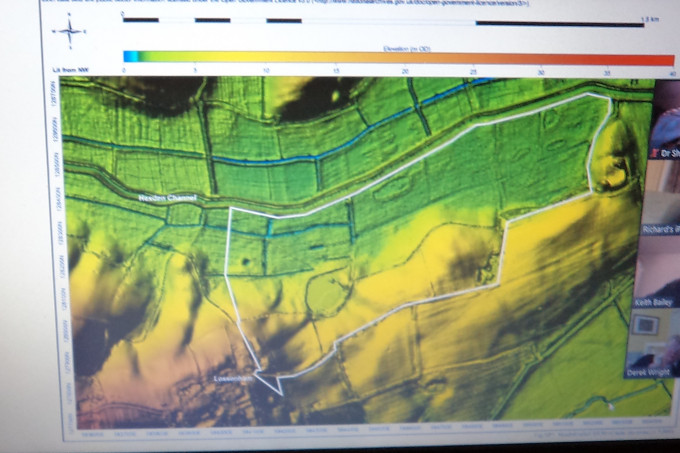

Now to this week’s events, in some ways two of these involve collaborations with Canterbury Archaeological Trust, with a meeting of the Kent History Postgraduates group sandwiched in the middle. Thus, firstly there was an online meeting of the Lossenham project this week to update people who might like to join as volunteers and/or are interested to know what has happened so far. For both the archaeologists and documentary historians COVID is continuing to throw up considerable challenges, and this meeting featured several from among the historians, with Andrew Richardson explaining the preliminary results from the electromagnetic survey and boreholes of part of the Hexden Channel landscape within the Rother Levels. In broad terms these results have highlighted the depth of the peat and that below the peat there is marine clay in this prehistoric valley. From the radiocarbon dates the peat was first being formed after the Last Ice Age with the top corresponding to 1400BC (middle Bronze Age). Consequently, Andrew is very excited that this will open up opportunities to investigate archaeologically an important prehistoric landscape, especially of the mid/late Bronze Age.

Coming much nearer in time, the historians highlighted what they hope to bring to the project. Ake Nilsen has lived in Newenden for 30 years and, as well as writing a short book on early Newenden, he has given numerous talks on the area. He is keen to be part of the team investigating the settlements in greater depth and he offered some research questions that he hopes the project will answer.

As a landscape historian, Brendan Chester-Kadwell is keen to investigate the impact of human agency on the Rother Levels and perhaps even more broadly. To give an idea of the type of evidence that is especially useful for such research, he showed the audience a map from 1633 that highlights the viewpoint of the local landholders of the time who saw the value of diverting the River Rother to make the land more productive for agriculture. As he indicated, such vested interests were an integral aspect of the way the landscape has changed over time as different groups vied with each other to control waterways, drainage and flood defences.

Richard Copsey brought in the Carmelite Friars whose medieval priory is central to the project. Richard has been researching the Carmelites since joining the Order and has built up an amazing archive of material, as well as publishing several books and articles, including one on Lossenham in Archaeologia Cantiana this year. Regarding the project, he is hoping the archaeologists will uncover more evidence about the layout of the buildings, especially in terms of the church and any claustral buildings. Moreover, if people are interested in the friars, he would like to hear from them and any prospective volunteers should please contact Annie Partridge in the first instance because she is co-ordinating the volunteers, as well as producing the monthly project newsletter.

Similarly, I would like to hear via Annie from anyone interested in working with me on the probate records. These primarily date from the late medieval and Tudor periods and into the 17th century. For the purposes of this short presentation, I focused on wills and what they can bring in terms of peopling the landscape, whether we are talking yeoman farmers, local artisans or the friars as recipients of alms and other largesse. Furthermore, having shown the audience such a will, I was able to point out how the various bequests can also offer ideas about families and neighbourhoods, farming practices, land holding and lordship, as well as religious affiliations through pious and charitable bequests.

Thus, as the project grows, more will be added to its website and in the meantime before the archaeology can get going, perhaps at Easter time, the historians will be holding a workshop. Although this has not been finalised, it may include an introduction to valuable primary sources, provide help in the reading of medieval and early modern handwriting and offer practical ideas about how volunteers can get involved.

Moving on to the Kent History Postgraduates, although not everyone was able to join because of other commitments, most people were present, and we welcomed Victoria Stevens who has just started on the St Alban’s Court Inventory project for her MA by Research. Moreover, there was a great array of Christmas jumpers, tee-shirts and earrings, so we were getting into the festive spirit, although, as Maureen said, the topic of her presentation wasn’t festive unless you count some of the victuals testators stipulated in terms of the feast after the funeral. More on that later because it sparked quite a discussion, but to begin Maureen outlined her doctoral research project to help the group’s newcomers. To recap, Maureen is investigating urban society from c.1250-1700 using Tonbridge as her case study. She is especially interested in the Stuart period because this was a critical time in the town’s development – in relation to the end of the castle as a military installation, changes in seigneurial influence, the shift from ‘hunting’ areas to agriculture through the break-up of the parks and chases, and the significance of migration.

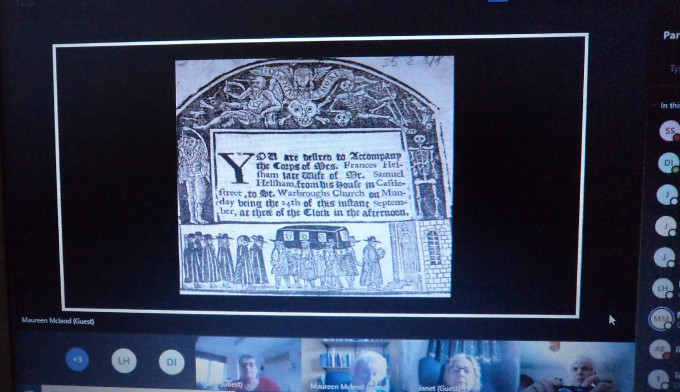

As Maureen highlighted, although wills do have their limitations, provided these are acknowledged such primary sources can be very useful regarding investigating topics such as occupation; property ownership and wealth, and networks – family, friendship and economic, the latter through landlords and tenants, overseers etc. Like others within the group, Maureen’s research has been heavily curtailed by COVID-19 due to the closure of archives, but she has been taking advantage of TNA’s policy of allowing the free downloading of PCC wills within certain prescribed limits. This has given her a good number of wills.

So what has she found for the 17th century? Well one of the findings is generally still a considerable interest in how the testator which to be commemorated. Much of this focused on the funeral, including the desire for a sermon, one testator specifying the biblical text the preacher should take. Others were keen to provide instructions regarding the wake and, even though often this centred on provisions for the poor, it might extend to friends and neighbours. Such funeral fare might consist of wheaten bread and beer, but others were more generous indicating they wanted meat (one mentioned a bullock), while another listed wine, beer, bread and cakes.

Moving on from her broad survey, Maureen used one of her ‘families’ as a case study to demonstrate how it is possible to reconstruct kin and other networks. In addition, by tracking the family over several generations she has been able to show how they enhanced their social position through their command of the law, for having started as scriveners they had become part of the gentry by the late 17th century. Their success in many ways parallels the development of Tonbridge because the break-up of the parks meant increasing work for those versed in property law who could draw up the necessary legal agreements required by landlords and tenants.

Her presentation generated a lively discussion about her findings concerning the provision of bequests to the poor in these wills, which led on to ideas about the provisions provided by the parish. In some ways Maureen is hampered by the absence of surviving overseers’ records, but the frequent testators’ confidence in the churchwardens as those who should see to post-mortem distributions of charity to the poor suggests their considerable knowledge of those designated deserving poor people. Moreover, as a mentioned earlier, the funeral feasts equally promoted several comments and this linking of charity and food has considerable continuity over time, including through to today.

This brings me to the Annual Becket Lecture which this year was given by Paul Bennett, Visiting Professor in Archaeology in the Centre. However, before introducing Paul I want to thank a couple of people for their help in making this go so smoothly. This was only our second venture into the world of online events and both Dr Claire Bartram and I were exceedingly grateful to Dr Diane Heath from the Centre for being alongside me to act as producer, while I acted as the chairperson. We were also grateful that Toby Charlton-Taylor from AV/IT was online with us to help if we hit any technical issues.

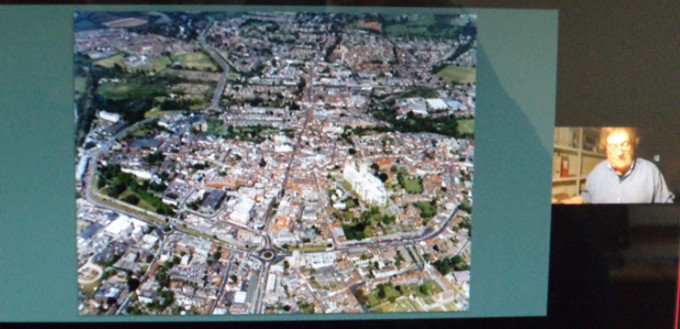

Now many of you will know that the Becket Lecture was inaugurated well over a decade ago by Professor Louise Wilkinson, who is now at the University of Lincoln – Canterbury’s terrible loss to Lincoln’s terrific gain, and, in some ways, it seemed fitting that this year it should be given by someone who has such close links to the Centre. Paul’s title of ‘Canterbury at the Time of Thomas Becket’ also seemed highly appropriate. For it allowed him to draw on that other great historian of Canterbury, William Urry, whose magisterial works Canterbury under the Angevin Kings and posthumously Thomas Becket his last days (through the efforts of the Rev Dr Peter Rowe) remain extremely important works. Nonetheless, Paul’s own contribution to our understanding of medieval Canterbury is vast for as the recently retired Director of the Canterbury Archaeological Trust after 45 years (as deputy and then director) he has ultimately overseen some very large archaeological excavations in Canterbury, including Longmarket, Whitefriars and Pin Hill, as well as smaller but equally significant sites too numerous to mention.

To begin his lecture, Paul recounted how he had met William Urry in the 1970s when he had been able to gain considerably from the great man’s intimate knowledge of the records, especially for the 12th and early 13th centuries, thereby allowing him to populate the city, the various religious houses and the surrounding suburbs. Paul also paid tribute to the work of his predecessor at the Trust, Tim Tatton-Brown, and more latterly regarding the city’s standing buildings Rupert Austin, as well as Mrs Margaret Sparks’ vast knowledge of the documentary sources, especially for the city’s religious houses.

Taking his large (in the region of 170 persons), international audience through Becket’s life, Paul highlighted the very limited time Becket actually spent in Canterbury, first as a member of Archbishop Theobald’s household and later as archbishop in his own right. Nevertheless, even this amount of time had presumably given him a good knowledge of his city, and even more that area under his jurisdiction such as the archbishop’s palace and Stablegate with The Borough, as well as at an earlier stage in his career the archdeacon’s house and chapel in the precincts of St Gregory’s Priory.

So Paul then posed the question of what would this city have been like in the mid to late 12th century. One of the fundamental points was that Canterbury was (and is) a walled city. On the alignment of the Roman wall much had apparently survived the ravages of time, albeit patching was certainly taking place, including between 1166 and 1168, Henry II seemingly using receipts from lands confiscated from Becket during the primate’s exile for this purpose – an irony presumably not lost on the king and his knights. The gates, too, were important, from St Mary Northgate with perhaps complete sections of Roman wall fossilized in the church’s nave to the still usable Queningate that would only cease to be employed in the mid 15th century with the building of the neighbouring gate and bridge over the city ditch. Medieval Burgate is known from the archaeology but not its Roman predecessor, while Newingate, known from a charter of 1153, would have been another gate familiar to Becket. He presumably also knew Ridingate, which was in some ways a shadow of its former Roman importance, and like the other main gates had a chapel associated with it, in this case incorporating the chapel of St Edmund Ridingate. Like the other gates and their arterial roads, Worthgate gave access down Wincheap (wagon market) and towards Wye, while the Westgate that Becket knew is now only know from a representation on a seal discovered recently by Mary Berg – see Archaeologia Cantiana 141 (2020).

Keeping with matters of defence and status, Paul outlined what Becket would have known of the two royal castles, the first constructed by William I following his success at Hastings and subsequent building works, including its great ditches forming massive inner and outer baileys. Indeed, the archaeologists are continuing to learn more about this outer work from the St Mary Bredin school site excavation. Then the second castle completed by 1120, which in Becket’s time would have been exceedingly impressive, with its massive keep and use of, for example Quarr stone from the Isle of Wight.

Turning into the city, Paul drew attention to the many mills along the river, the water meadows and gardens, and the street pattern. For little has changed since Becket’s time, one of the very few changes being the punching through of Guildhall Street in the first decade of the 19th century. Yet some roads would have been narrower as St Andrew’s church, for example, formed a middle row in the High Street and other churches ‘encroached’ into today’s roadway. Indeed, in Becket’s time the city was alive with parish churches, and among these 22 churches in addition to Queen Bertha’s oratory at St Martin’s, a further four were from before the arrival of the Normans: St Mildred’s, St Peter’s, St Dunstan’s and St Alphage’s.

Nor was the city’s spiritual life the only mark of its success because there were numerous specialist markets, as well as the main market outside the earlier Christ Church gate. These markets offered trading opportunities, but then so did the many shops, including the 80 shops between the Burgate and the Bullstake (Buttermarket). Although nothing survives above ground of these premises, some stone cellars do, including at the corner properties of Mercery Lane and the High Street, that under Pret having a double cellar. Yet even if the timber-framing above does not survive, the property boundaries very largely do, as highlighted on the Urry maps associated with his Angevin Kings book. Furthermore, as Paul noted, this is where archaeology has joined forces with the documentary evidence for amongst the findings at Longmarket, for example, were Terric the Goldsmith’s workshop, and in the Westgate area the pottery kiln of an immigrant potter from this same period. Of course, this is not the only evidence of the use of clay, for the tile industry is known from excavations at Tiler Hill to the north-east of the city. Furthermore, it was not only locally made pottery that was in use in Canterbury for the archaeologists have evidence of luxury wares from Africa and the Middle East. And this vigorous, thriving cosmopolitan city meant that properties were often subdivided, especially in Canterbury’s central areas. Equally, some residents had considerable properties, and moneyers can be found in the rentals holding properties in the Stour Street, White Horse Lane, and Best Lane area, which also was home to many within the city’s Jewish population.

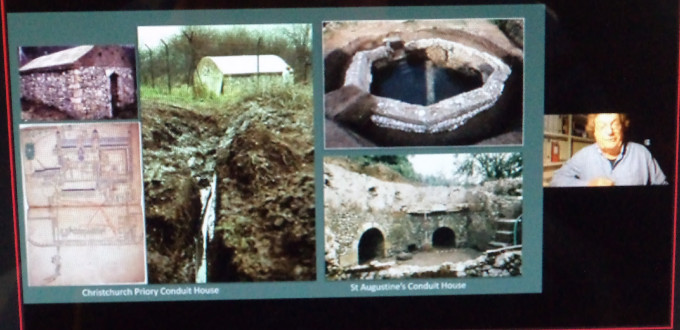

Turning to the city’s religious houses, both inside and outside the city wall, Paul took his audience on a tour of Christ Church Priory, and then the other great Benedictine monastery of St Augustine’s Abbey, albeit we are more fortunate for the former because of its transformation into the New Foundation post Dissolution and the survival of Prior Wibert’s waterworks plan – see the Wren Digital Library at Trinity, Cambridge: https://mss-cat.trin.cam.ac.uk/manuscripts/uv/view.php?n=R.17.1&n=R.17.1#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=569&xywh=-2543%2C-1%2C7977%2C3954 (thanks Paula) Nonetheless, even though the work of earlier archaeologists is challenging to interpret, much can still be pieced together regarding what the great abbey would have comprised in Becket’s time.

For some of the other religious houses this is even more challenging, as in the case of St Sepulchre’s Nunnery and St James’ Hospital, but the archaeologists have discovered much about St Gregory’s Priory, while the mix of archaeology and standing buildings at St John’s Hospital confirms the importance of this Lanfranc charitable institution. Paul provided much more detail, but I think I will leave the religious houses here and just mention that between the Trust’s own publications, those of English Heritage and the books of Mrs Sparks and others, there are good sources for those wanting to explore further.

Instead, I’m going to leave you with a few of the many comments Paul’s lecture and his subsequent answers during the Q&A session engendered: “Terrific lecture, thanks so much”; “that was a fantastic and interesting answer to my Becket question”; “Congratulations on a fantastic presentation”, and “thank you for an extremely invigorating presentation”. And I would like to add my heartfelt thanks to you Paul for such a brilliant lecture and I know I speak for Claire, Diane and I’m sure for Louise too. This brings me to the end of the last of the Centre’s bogs for 2020, and I shall look forward to reporting again in 2021, and in the meantime I wish all readers a safe and enjoyable Christmas.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1977

1977