Having had two weeks off, which gave me a chance to write a paper and almost finish an article, I thought this week I would start with a brief reminder about two Centre events in September: the Parish Histories conference and the Michael Nightingale Memorial Lecture.

Bookings are now being taken for the one-day conference on Saturday 21 September on ‘Revisiting sources and themes in parish histories’ at www.canterbury.ac.uk/parish-histories or email artsandculture@canterbury.ac.uk which will bring together experts in researching the history of the parish. We are very fortunate that among those contributing to the day will be Professor Beat Kümin, from the University of Warwick, who has worked extensively on the English parish to explore political agency, religious life and social exchange in these local communities during the early modern period. Others joining us will be Professor John Craig (Simon Fraser University), who has two exciting projects at the moment, the first on a study of the politics of reading in the English parish, 1536-1642, and the second on the soundscapes of worship in early modern England and the cultural politics of prayer. The day will start with an exhibition of parish records at Canterbury Cathedral Archives, led by Cressida Williams the manager there, before we head to Old Sessions House for the lectures and plenary panel. Among these will be a presentation by Dr Valerie Hitchman (University of Kent) and Nick Edwards (University of Warwick) on ‘The churchwardens’ accounts database’ that is now hosted by Warwick University’s Network for Parish Research. If this sounds interesting, please do have a look at the webpage for further details and booking, and we shall look forward to seeing you there.

The work of the Birmingham Guild Ltd

The other event I want to mention is the 8th annual Michael Nightingale Memorial Lecture that will take place on Tuesday 24 September at 7pm in Old Sessions (wine reception from 6.30pm). Moreever, before the lecture, Professor Rama Thirunamachandran, the Vice-Chancellor at CCCU, will give certificates to those receiving Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Awards in recognition of their research into Kent history topics. This year the lecture will be given by Professor Carl Griffin (University of Sussex), who will be exploring the aftermath and implications in Kent of the Swing Riots of 1830. As a joint undertaking between the Centre and the Agricultural Museum Brook, it is excellent to be able to bring new groups to CCCU. In the past we have had some great evenings, and I believe we are in for another such time this year. Booking is not required, so please do come along to this public lecture at which there will be a voluntary retiring collection.

Keeping with the early modern and modern periods, I thought I would offer a snapshot from the documentary sources for one of Canterbury’s fascinating buildings – the ‘old’ Boots store on the corner of Mercery Lane and the Parade and which is now the home of Pret A Manger. For those of you who remember Boots the chemist at this location, you will remember that it included the neighbouring premises, but for the purposes of this blog I’m going to keep to the corner plot and, even then, just mention a few owners.

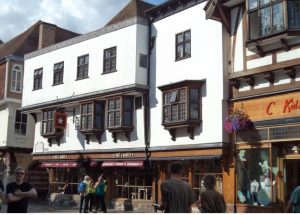

The building as it is today

However, first for those who don’t know Canterbury, why this building? Well, this corner plot is possibly at the most important cross roads in Canterbury. The junction is at the heart of the medieval city, marking the point where the processional way from the royal castle to the cathedral, the seat of the archbishop of Canterbury and the powerful Benedictine monastic house of Christ Church, met the city’s main thoroughfare. Another indication of its significance is land ownership, all four corner sites were acquired by the great monastic houses of Christ Church Priory or St Augustine’s Abbey during the Middle Ages. Three of the four, including the north-east corner (Boots) were in the hands of Christ Church, which reflects the priory’s overall landholdings in the city compared to those of St Augustine’s. Together these extremely wealthy houses controlled a very large proportion of the city’s real estate, allowing them to have a marked influence on the commercial development of Canterbury. Consequently, Christ Church’s prosperity, in particular, was strongly linked to the wellbeing of the city, successive priors keen to develop and sustain their commercial and domestic properties, especially in central parishes such as St Andrew’s.

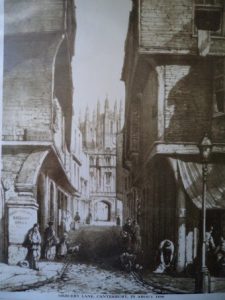

As it was in the 1850s

Following the religious and political changes of the mid 16th century, the site diagonally opposite to Boots was added to the corporation’s property portfolio (it had been confiscated by the Crown at the dissolution of St Augustine’s Abbey and, thereafter, was bought by the corporation with the rest of the abbey’s city holdings); whereas the priory’s holdings seemingly passed intact to the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral. For the city and cathedral authorities this area retained its importance, partly as a source of revenue but even more through its continuing value as a desirable residential and retail area. This seems to have held true over the next few centuries, the streets home to relatively genteel professions such as booksellers, stationers and goldsmiths, though the rear of these properties on Mercery Lane and The Parade were close to the premises of several butchers in and around Butchery Lane.

Another development that had an impact on the character of this area was the subdivision of many local properties in the 18th century, though unlike some parts of Canterbury, this did not lead to the creation of poor densely populated squares and alleyways. Instead, the locality appears to have maintained its ‘middle class’ status, its residents continuing to live and trade at the numerous small shops and other premises. In part this was presumably due to the proximity of the cathedral and its community of clerics and other members of the professional classes, its ambiance enhanced by the demolition of St Andrew’s church in 1763, thereby opening up The Parade (the church was relocated to a space behind the buildings on the south side of The Parade). However, the proliferation of small family businesses located in rented property, mainly belonging to the Dean and Chapter, and a few apparently freehold units, may have led to a decline in the physical state of the housing stock as shown by a number of mid to late 19th-century illustrations. One possible explanation is the Dean and Chapter’s unwillingness or inability to undertake a sustained maintenance programme because the rents it received had seemingly become fossilized by this time.

Showing the quality of the restoration work

The slide into decay of what was seen as one of the most picturesque locations in the city was halted by the combined efforts of the city council and Boots in the inter-war years of the 20th century. By this time there was a feeling among certain sections of the local populace that the city was in danger of losing its medieval heritage (though this did not stop the neglect and subsequent demolition of a considerable number of other medieval buildings throughout the century) and Boots’ actions to renovate the corner premises and subsequently the adjacent properties in such a way as to retain this heritage were applauded by the local press. Even though this area was increasingly dominated over the later 20th century by national retail outlets at the expense of local businesses, it was and is still seen as attractive by tourists and residents alike.

So who were some of these 18th-century shopkeepers? In 1730s the corner tenement was occupied by Margaret Fenner, the widow of Enoch Fenner, bookseller and stationer, who had lived in St Andrew’s parish. Although the evidence is not conclusive, it seems likely that Enoch’s place was the corner tenement, the property comprising a kitchen, buttery, wash house, yard and shop on the ground floor, the staircase and passage leading to the upper rooms of the little fore chamber, the best chamber, the back chamber and the maids’ chamber. The property also had a cellar in which he kept his brewing equipment, coal and wood (even today the corner property has a double cellar). There was a bed, case of drawers, desk and 6 cane chairs in the little fore chamber, but the best bed, which had ‘blew china curtains’ was in the best chamber. This seems to have been a large room because amongst the other furniture there was a wainscot case of drawers, 9 chairs and a corner cupboard. Like the maids’ chamber, there was a fireplace, and Enoch also stored 57 pictures in his best chamber. Nevertheless, it is his shop that is the most interesting because the appraisers listed items such as a standing press worth £2 and 3 small presses worth a further 5s. His stock was considerable, ranging from a set of cartoons, to 2 sets of battle pieces and hundreds of prints of various sizes. He also sold maps, having ‘7 Simmons maps of Kent’, 90 other maps and 187 sheet maps. The book collection was even more extensive and the appraisers carefully listed them by title and author, grouping them under ‘Folios new’, ‘Folios old’, ‘Quartos new’, ‘Quartos old’, ‘Octavos new’, ’12 mo & 24 mo’. He also had over £100 of stationary items in his shop at the time of his death, including different sorts of paper, quills, books for music, various quality skins and slates.

More of the Birmingham Guild’s work

Although Margaret may have continued the business, the inventory noted that the books were to be returned to a Mr Knaplock. Yet the books were not valued until 1734, five years after Enoch’s death, which might imply that she did trade during those years. She outlived her husband for a decade and in her will she intended that her two children should have equal shares in her estate. For Thomas Smith, her son-in-law, this seemingly aided his position because after the death of his mother-in-law he acquired the corner property, trading as a bookseller. He appears to have remained there for several decades, being succeeded by William Bristow, another bookseller, who was the occupier in 1800.

For more than a century, therefore, the proprietors of the corner tenement were booksellers, and it is possible that even before 1700 the place was a bookshop, perhaps belonging to Nicholas Johnson who traded in St Andrew’s parish until his death in 1671. Johnson’s inventory does not include a list of his books, but Enoch Fenner’s stock may provide some ideas about his clientele. A considerable proportion of his books were theological and service books, presumably catering for the large community of clerics in the neighbouring cathedral precincts and at the many parish churches in Canterbury and its hinterland. Most of the cathedral clergy were university trained, which meant that they were also interested in medicine, the natural sciences, and the classics. Furthermore, the professional classes in Canterbury probably patronised Fenner’s shop, buying similar volumes; yet it would be interesting to know who purchased items such as ‘Cleopatra a Romance’, ‘Sterlings Plays’, ‘Burton of Malencholly’ and ‘Starings Marriners Magazine’.

Looking at the lead work and a bush!

When Boots bought it, the corner tenement was in an extremely poor state, although the full extent of the damage only became clear once the timbers were exposed. The city council’s officers seriously considered demolition but the building was saved by Boots’ willingness to fund an extensive reconstruction programme in 1931. The firm’s own architect, Percy J. Bartlett, prepared plans which would allow the building to blend into its medieval surroundings, and the decorative plaster work, lead work and joinery were undertaken by the Birmingham Guild Ltd. This firm had started in the late 1880s as the Birmingham Guild and School of Handicrafts, part of the new arts and crafts movement of the late 19th century. In order to survive, the organisation became more commercial following a series of mergers with other firms in the Birmingham area. As a consequence of their work, Boots was able to provide its customers with a range of departments, from the surgical department in the basement to the spacious library lounge on the first floor. By so doing Boots, without knowing it, was keeping alive a tradition of book selling on the premises that had lasted, with interruptions, for over 250 years. Following changes in retailing practice, however, the library was a casualty of the modifications Boots made to the premises in 1959-60, a time when the firm also made considerable alterations to the adjoining premises in Mercery Lane and The Parade. More changes followed, and after Boots acquired Nos 5 & 6 The Parade the firm commissioned a substantial modernization programme. Working in close co-operation with the city council’s planning department, Boots refurbished the interior of its large store in 1989 seeking to balance current commercial demands and the need to preserve what remained of the medieval building. However, 15 years later the store was relocated to new premises in the redeveloped Whitefriars shopping complex. Today the Mercery Lane/The Parade corner property is a place to drink coffee and admire what remains of this post-Black Death medieval building that forms its core, not that I am endorsing or otherwise the coffee, it just happens to be the retail unit there.

Next week I hope to have some preliminary news about Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2020.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2713

2713