The Easter holidays are often busy as conference organisers seek to fit in their particular offering and this year is no exception.

Consequently, I’ll begin this week with Abby Armstrong and Harriet Kersey’s ‘Family and Power in the Middle Ages’ conference that took place under the auspices of the Centre last weekend. This very friendly gathering of medievalists brought together a thoroughly international group of people from Norway, Portugal, Belgium, Turkey and the USA; oh and one or two from the British Isles! This meant the topics covered and the noble families mentioned were similarly international: from David Thornton’s exploration of naming practices in early medieval Ireland in the west to Alexandra Vukovich’s study of early Rus princely hierarchies in the east; and Barbora Davidkova’s assessment of ‘evil’ queen-mothers in the St Olaf saga in the north to several papers that drew on Iberian medieval families in the south. Due to the limitations of space, I’ll confine my remarks to Kent matters, but in no way should this be seen as detracting from such a richly diverse feast of a conference.

Harriet overseeing questions to the speakers

From a personal perspective, it was lovely to greet old friends such as Dr Jennifer Ward and to meet for the first time, I think, Professor Lindy Grant. Their respective keynote lectures were fascinating because I really knew very little about Blanche of Castile, Lindy Grant’s subject, but Jennifer Ward’s topic of noble grandmothers was closer to my area because she primarily drew her examples from late medieval England, and included a couple of Kent references.

The first of her Kent references was the grandmother-granddaughter relationship of Elizabeth de Burgh and her granddaughter Elizabeth the daughter of Elizabeth’s daughter, yet another Elizabeth, and Henry Lord Ferrers of Groby. The early deaths of Henry and his wife in 1343 and 1349, respectively, meant that the young Elizabeth, and William and Philippa, her siblings, benefitted from growing up in their grandmother’s household, and it was ideas of grandmotherly influence in terms of religion, household management and noble culture that Jennifer wished to highlight. This younger Elizabeth is commemorated in Ashford parish church having died in the town while married to John Malmayns. Although her brass is now no longer complete, it is probably worth giving in full the entry from Hasted’s History of Kent, volume 7 (c.1800). This states: ‘holding in her left hand a banner, with the arms of Ferrers, Six masctes, three and three, in pale; which, with a small part of the inscription round the edge, is all that is remaining; but there was formerly in brass, in her right hand, another banner, with the arms of Valoyns; over her head those of France and England quarterly; and under her feet a shield, being a cross, impaling three chevronels, the whole within a bordure, guttee de sang, and round the edge this inscription, Ici gift Elizabeth Comite D’ athels la file sign de Ferrers . . . dieu asoil, qe morust le 22 jour d’octob. can de grace MCCCLXXV.’ If you don’t know this church, I would recommend a visit because even though it has been the subject of considerable renovation, it is still interesting and the setting is special in what is otherwise no longer an attractive medieval town compared to others in the county.

Louise introduces Jennifer Ward

Jennifer’s second Kent reference was to the Dominican nunnery at Dartford. The grandmother-granddaughter relationship this time was between Cecily Duchess of York, who is known for her piety amongst other things, and Bridget the daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Bridget was the youngest of King Edward’s daughters, and, like her siblings and parents, there is an image of her in the stained glass window close to the martyrdom in Canterbury Cathedral. However, the important matter regarding this female network is that Bridget was a nun at Dartford and while there she was the recipient of three books in her grandmother’s will: ‘a copy of the Legenda Aurea in vellum, a ‘boke‘of the life of Saint Kateryn of Sene’ and a ‘boke of Saint Matilde’’. Although, Jennifer did not mention it (unless I missed it), Cecily also remembered another of her granddaughters. She bequeathed ‘a boke of Bonaventure and Hilton in the same in Englishe, and a boke of the Revelacions of Saint Burgitte’ to Bridget’s cousin, Anne de la Pole, who was said in the will to be the prioress of Syon Abbey (Paul Lee, Nunneries, Learning and Spirituality … Dartford, p. 169). A number of historians have explored female networks fuelled through the giving and receiving of books during this period, including Carol Meale, Felicity Riddy and Julia Boffey, and it was good to hear details of the Dartford Priory example again.

The only other paper I attended that included Kent references was that given by Sam Howden. Sam is a doctoral student at the University of Lincoln who is studying a little known 13th-century bishop of Lincoln Richard Gravesend. Now the name rather gives it away because his family came from north-west Kent. Using the bishop’s register and other documents, Sam demonstrated how he had discovered the identities of the bishop’s household and how Richard had used his position to aid several men from Kent, as well as Oxford where he had attended university. Some of these men, depending on whether they were clerics, were given administrative posts, thereby allowing the bishop to build up a loyal following during a particularly difficult political period when the country was for a time in the mid-1260s engulfed in civil war. This baronial war against Henry III by Simon de Montfort’s forces, and in particular the involvement of Simon’s wife Eleanor, who was the king’s sister, has been studied by Professor Louise Wilkinson, and she was especially interested in the identities of the bishop’s affinity and entourage because the names Sam mentioned were known to her. Similarly, Janet Clayton, a doctoral student in History who is researching Scadbury Hall, its owners and their London connections, was aware of some of these names, which meant Sam’s paper was of particular interest to her as well. This means Louise and Janet will hopefully be able to share information and ideas with Sam – one of the primary benefits of a conference like this!

Abby chairing the final session

The second conference I want to mention, albeit much more briefly, was at the University of Huddersfield and focused on the material culture of religious change between 1400 and 1600. Again, this was very much an international affair in terms of those giving papers and the topics they covered, which means that as before I’ll keep to the Kentish examples. Within these, too, I keep to the more substantial examples because Dr Patricia Cullum, in her assessment of the heraldic devices of senior clerics, examined the coats of arms of several 16th-century archbishops of Canterbury.

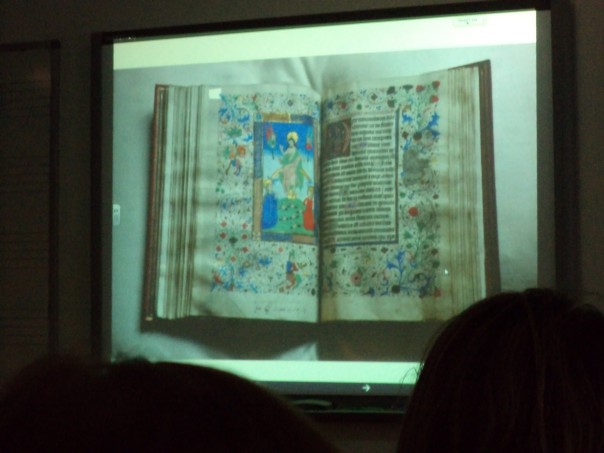

However the two papers that primarily used Kentish evidence were my paper on the use and abuse of objects as seen through the lens of the depositions collected by Archbishop Cranmer in 1543, and Dr Helen Matheson-Pollock’s analysis of the Hever Book of Hours that for some of its history resided in the Boleyn family home of Hever Castle. Having written about the Prebendaries’ Plot before, including last week as part of the blog on the Tudors and Stuarts Weekend, I’ll confine my comments here to a couple of examples that I think are rather interesting. They concern the protection of images/relics rather than their more usual destruction and the first shows how the parish church could become a refuge at this extremely difficult time. Thus, Chilham parish church to the south west of Canterbury would seem to have been in the control of Catholic sympathisers who were prepared to offer a place of safety for St Augustine’s shrine [reliquary] that had been spirited out of St Augustine’s Abbey. Whether it was destroyed once its hiding place was known I don’t know, but it is an intriguing scenario. Thomas Bleane of Great Mongeham used a slightly different tactic, but presumably was no more successful in his attempt to give refuge to a cherished sacred object. He kept an image by his seat [pew], but decorating it with three crowns was probably not a smart move if he didn’t want to draw the authorities’ attention to his activities, and that too may have met the same fate.

Helen discusses Anne Boleyn’s marginal note

In the early 16th century, the first owners of Helen’s Book of Hours would have seen it as a very special object for it contained vital prayers and liturgical services for the spiritual well-being of the reader. Produced in Bruges for the English market (it has the Use of Sarum), it may have been purchased by Geoffrey Boleyn, Anne’s grandfather and so part of the family’s possessions, whether in London or at Hever Castle. All of this is interesting, as are the beautiful illustrations, but the focus of Helen’s paper was the eight inscriptions added by various individuals between 1520 and 1590. Even though not all of these writers can be identified, among those who included their name are Anne herself (the earliest c.1521 using French), Elizabeth Seymour, Cecily Baker, Elizabeth Parr, Henry Cobham and Anne or Anthony Poyntz. Thus, we have a roll call of many of the major gentry families of west Kent who were busy expanding their territory and influence in the county, and at London and the royal court, and who were the holders of such residences as the castles at Leeds, Allington and Cooling; as well as Sissinghurst and Knole. Connections among these families were founded on marriage, but also matters of religion, neighbourliness, business and shared interests based on books, learning and a sense of Kentish identity. Although Helen has yet to decide just how to explore the book’s significance, her paper offered fascinating insights that chimed with the conference’s aims to look at religious continuity and change in the production and use of material culture during this crucial period. Indeed, many of the papers achieved this end and it was a most enjoyable and interesting conference.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2321

2321

the malmains family are descended from the ellis family i believe like half of kent noble families. descended from guillaume d’alys sheriff of hampshire,also know as alys.helles alis.ellis hales and hills. elias de shillingheld of chilham is one and my ancestor. the avranches earls of chester and many others, all descended from guillaume d’alys of haute normandie sheriff of hampshire under william 1st two of mine from kent walter and john de shillingheld fought at the siege of acre/akkar and the march on jerusalem .something im extremely proud of and its recorded,another one there was archibald ellis. they all descend from louis the pious king of the western franks and holy roman emperor and her sovereign royal majesty queen elizabeth 2nd is descended from him too,the house of guelph.i noticed we held lands from the templars at ospringe too.im suprised nobody has written a full history of these apart from the one written by ellis in the 1800s which is really good history.the deerings of lenham are also descended from the shillinghelds daughter katherine formerly the widow of chiche the monier of canterbury, part of archbishop chichelys family its believed, her father william de shillingheld gave evering acre manor as dowry

i forgot to add,all these families carried the fleur de lys on their armorials as descendents of the kings of france

Dear Robert, thank you for all the information about your ancestors, I’m sure other readers will be very interested in this.

Regards, Sheila