Faversham’s history – attracting a growing audience.

On Wednesday evening, the Canterbury Christ Church University bookshop hosted the launch of Michael Jones’ new book on the Black Prince, but before I give a short report on that event, I just want to mention a conference that took place in Chartham last Saturday.

The Guild of One-Name Studies holds seminars and conferences regularly all over the country and last Saturday was Kent’s opportunity to showcase the wealth of documentary materials that are housed in Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, as well as also mentioning those deposited at the Kent History and Library Centre at Maidstone and the Medway Archives at its new home in Rochester. Indeed, quite a large proportion of Saturday’s audience had taken the opportunity offered by Cressida Williams, the manager at Canterbury, to visit the archives to see for themselves some of its special documentary sources. The theme on Saturday was ‘Catalogues, Collections and ArChives’ and, as the first speaker, Cressida provided an introduction to the range of Church records held at Canterbury from Anglo-Saxon charters to parish magazines from the period of the Great War. For the archives have UNESCO Memory of the World status, the only monastic collection to have achieved this because at the heart of the archives is the wonderful collection of records from Christ Church Priory that after the Reformation became a Dean and Chapter that was similarly bureaucratic! Nor is this the only large collection because, at least at present, the cathedral is also home to part of the diocesan collection with its wonderfully rich ecclesiastical court records – from tithe cases to heresy and witchcraft.

Sheila Sweetinburgh exploring Canterbury’s medieval civic archive

Cressida discussed the value of such records to those studying particular surnames, as well as the societies in which these people lived and worked, and the same themes permeated throughout the day. Thus for the second lecture, I took the audience on a virtual tour of Canterbury city’s civic archive to demonstrate the importance of these diverse sources and just what categories of information they might provide about late medieval townspeople. Even though men are far more visible than women and children hardly at all, all is not lost, and it is possible to find evidence of the activities of women as independent traders, armed robbers and plaintiffs in court cases. In addition to the chamberlains’ accounts, we also examined a couple of wills from the 1380s recorded in one of the city’s most fascinating manuscript. These spoken wills were written down by the common clerk because they involved the inheritance of property within the liberty, as in the case of Agnes Rogner. She bequeathed her tenement in Brodestrete in the parish of St Mary Northgate to her husband John, and even more useful in terms of placing this property all the abutments are listed, such as the tenement of the heirs of Alice Poterfeld towards the east. For not only are the names valuable, but the preponderance or otherwise of property in the hands of heirs can offer ideas about such matters as levels of mortality and levels of discontinuity within families.

Even though most of these documents are in Latin, during questions we did discuss how researchers can try to overcome such difficulties, as well as the value of taking courses on palaeography and the need to follow these up with lots of practice, preferably in the archives rather than relying just on digital images on the internet. After this lively debate and a very good lunch, the audience settled down to listen to Dr David Wright’s presentation on probate records. David, too, highlighted the importance of going to archives instead of merely relying on online sources, and he also explored the range of information that can be gleaned from the probate calendars and catalogues that are available at The National Archives at Kew. In addition to what you might expect among the probate records such as wills and inventories, David drew his audience’s attention to administrations, which may be the only place where vital family ties and names can be found, as well as occupational details and other information that can put flesh on the bones of these people from earlier centuries. Much of this information about probate records and their value to the family and social historian is available in David’s publications, copies of which he had for sale at the tea break later in the afternoon.

Keeping with the Kent records theme, the final lecture was given by Peter Ewart, another well-known Kentish historian. Peter, too, explored Church records, although this time from the parish collections because he concentrated on what the records of the overseer of the poor could bring to those studying individuals and families. As he noted, the Elizabethan and Victorian poor laws functioned for about 400 years before the more enlightened system that we have today had its beginnings, and being based on the parish effectively covered the whole country. Moreover, these accounts not only provide evidence about the poor and their daily lives, but also are informative about those who contributed, giving information about their property as part of the calculation regarding what each should contribute. Peter was especially keen to demonstrate the importance of settlement certificates because they, like David’s administrations, can often provide details not found anywhere else.

A fifth speaker, Dr Nikki Brown, demonstrated some ideas about presenting statistics using the name she has been researching, but I’ll leave this aside because it has no bearing on Kent sources. However I do want to echo the comments of several people I heard who said they had greatly enjoyed the day, the breadth of the knowledge displayed by the speakers, the excellent refreshments and the friendly atmosphere. Consequently, I think, the organisers should be congratulated for devising a very successful day.

Michael Jones discusses the Black Prince.

Moving on to my second event, Michael Jones’ book launch (Michael had been one of the speakers at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend in 2016), it was great to see a wide variety of people gathered in the foyer of Laud to hear Michael give a short talk on why he thinks the Black Prince has been misunderstood and undervalued by historians in the past. As Dr David Grummitt, Head of the School of Humanities, said in his introduction, Michael has written a number of biographies on complex historical figures. Indeed, it might be said to be his forte and this new work on the Black Prince is no exception, bring excellent archival skills to bear in an imaginative way that makes his works very readable.

Among the points Michael raised in his talk was the attitude of contemporaries to the Black Prince’s death, especially those of the French court, that is those he had fought against during much of his lifetime. For contemporaries valued him as a military leader, as the epitome of chivalry, and as someone who today might be said to have always played with a straight bat. Sorry, but as an ex-cricketer there are analogies here because if the Black Prince had been a cricketer he would have been widely regarded as someone who walked even before he was given out. But to return to Michael’s assessment, he was keen to stress that like all human beings the Black Prince had flaws, but that equally he displayed virtues such as his loyalty to his friends, his sense of humour, and his piety that seems to have been far more than skin deep. Amongst other matters, he had a deep devotion to the Trinity, and also to St Thomas of Canterbury that became especially fervent following the Prince’s victory against the odds at the battle of Poitiers. Consequently, Michael feels it is not surprising that he wished to be buried close to the saint in Canterbury Cathedral, albeit his chosen resting place was the crypt, which probably also says something more about the man than the location of his actual funeral monument close to Becket’s shrine. This word picture of the Black Prince was greatly enjoyed and after taking some questions, Michael, as you can see, sat down to autograph a succession of books that eager members of the audience had purchased from the bookshop.

Michael Jones and an eager purchaser.

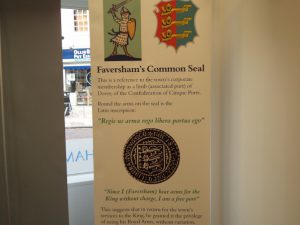

Finally, I want to turn to a public lecture last night organised by Faversham Town Council, especially Cllr Nigel Kay, Louise Bareham Town Clerk, and Hannah Tilley, Tourism Officer, at its new history and heritage centre close to the Guildhall in the market square. A capacity audience came to hear about the Cinque Ports in the Middle Ages. As a way of giving the talk a focus, I concentrated on mayor-making, other civic elections and the holding of town courts after a general introduction to the Ports as an association as much as a confederation. Even though the Faversham custumal does give a reasonable level of detail about the election of its civic officers, including where the Burghorn was to be sounded – at the crossroads in the town, I did use Sandwich and Dover as my main case studies because the records are even better. Furthermore, I was keen to explore ideas with the audience about how these Ports had used sacred space both for civic elections, in some cases up to the 19th century, and the dispensing of justice, and, unlike Faversham, many of the other Ports (including Members) had deployed church spaces, even after building guild/town halls.

The keen audience at Faversham.

Faversham is lucky that it has a long history of historians who have worked on the town’s records. Although I have done some work on these, I am fortunate in being able to draw on the work of Dr Justin Croft (who completed his doctoral thesis on the custumals of the Cinque Ports, using Faversham as one of his case studies), Duncan Harrington and Patricia Hyde, and for the Cinque Ports more generally, K.M.E. Murray. With these resources at its disposal, I’m sure the new centre will go from strength to strength and I will be delighted to meet the ‘team’ again in the autumn to hear about their plans for 2018.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1130

1130