In contrast to the previous fortnight, this week has been much quieter with regard to history lectures open to the public, except for Dr Martin Watts’ talk at St Peter’s Methodist Church on Thursday evening. This was organised by the Canterbury Festival as a marker that 2016 is an important anniversary for the Battle of the Somme. Martin focused to a large degree on the casualties suffered by, among other regiments, the Buffs and the West Kents, as well as drawing out the implications of the battle in terms of what was learnt by both those in high command and across society – a time of lost innocence regarding modern warfare. Others involved with the Centre have also been busy, and I thought I would report a few exciting items before offering a few snippets from the archives because I have missed being able to get on with my own research into the businesswomen of late medieval Canterbury.

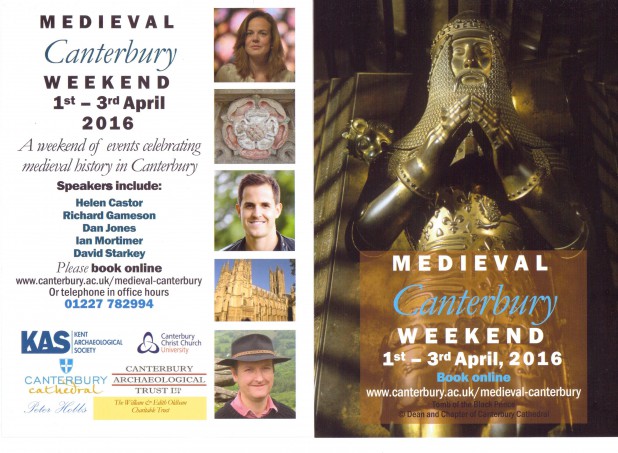

So, firstly, the organising committee for the Medieval Canterbury Weekend is delighted to announce that Professor Michael Hicks has joined as a lecturer for Sunday 3 April. He is replacing Dr David Grummitt, who has unfortunately had to pull-out of the Weekend, and thus Michael Hicks’ lecture will begin at 11am and will be in the Kentish Barn, part of Canterbury Cathedral Lodge within the precincts. As some of you will already know, Professor Hicks is an expert on the Wars of the Roses and a very distinguished scholar of late medieval England. As the author of numerous books and articles, and a well-respected speaker on the tumultuous years of the later fifteenth century, he has an unrivalled knowledge of the major personalities of the time. Consequently we are very fortunate that he is going to be speaking on the kings (and queens) who ruled, it must be said, often quite disastrously during the Wars of the Roses, giving us his considerable insights into how and why this occurred. This will fit very nicely into the programme because one of the following lectures is Dr David Starkey’s assessment of Henry VII, the first of the Tudor kings.

Keeping with the medieval theme, it is great to be able to mention that Dr Diane Heath has published an article in the February edition of History Today on emotional responses to pilgrim tokens, as witnessed by the sewing in of such tokens into books of hours (she focuses on such a book in Canterbury Cathedral Library). Having recently successfully completed her doctorate at the University of Kent on the meanings and uses of the medieval bestiary in monastic culture, she is developing her analysis to explore emotional responses in medieval piety, hence her foray into the use of pilgrim tokens. She was also busy this week giving a talk to the Whitstable local history society on various aspects of her research, especially the complex meanings attached to particular animals and how these were intended in the Middle Ages to aid the study, through memory, of theological truths. Diane is also heavily involved in the organisation of the Medieval Canterbury Weekend, which is now less than two months away.

Dr Martin Watts’ activities have already been mentioned, but he is also involved in organising a one-day conference on ‘Richborough through the Ages’ that will take place on Saturday 25 June, and, as well as featuring Canterbury Christ Church staff: Martin, Drs Paul Dalton, John Bulaitis and Lesley Hardy, will include speakers probably known to readers, such as Keith Parfitt of Canterbury Archaeological Trust and Ges Moody of the Trust for Thanet Archaeology. It promises to be a fascinating day and although covering a very broad timescale, is likely to bring forward common themes as we move through the day. Full details will be available shortly and I’ll let you know when they come out.

Finally, I thought I would return to the Middles Ages and some interesting cases from the city’s courts, the records of which are now cared for by Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library on behalf of the City Council. I’ll leave aside the bear and ape, and the activities of Alice and the Austin Friars for another occasion, and instead link to two of the lectures that will feature at the Medieval Canterbury Weekend, that is ‘public nuisance’ and perceived ‘abuses of the written (in this case printed’ word’. So to begin with Professor Carole Rawcliffe’s topic of public nuisance, among those brought before the city’s courts in the early sixteenth century was one Joan Ward who lived in Duck Lane, and, as well as being indicted as a common scold, she was presented for polluting the common well through her washing of ‘filthy vessels and clothes’ and tipping the foul water back into the well. Nor was she alone in such nasty activities because John Noble, a local cobbler, was up before the courts for emptying filthy chamber bowls [pots] in day time into the king’s street, something he had done ‘diverse times’ – obviously a charming individual! Such activities can be seen as the spice of life, and Professor Rawcliffe will, I am sure, present a lively talk on such cases and how various authorities sought to combat the more unpleasant activities of the locals.

Professor Peter Brown’s assessment of the uses and abuses of literature during the age of Chaucer will be less graphic in terms of such activities. However such abuses were perceived by contemporaries as even more serious for the commonweal (community) than John Elys allowing (perhaps directing) his servants to sweep the dust from his house into the street; or those contracted to carry waste, including tubs of stinking blood, from the butchery to the suburbs at night, but who instead had been doing it during the day. Indeed, the power of the word was well understood by contemporaries, hence the furore over the pinning of an anti-Lancastrian ballad to the Westgate in early June 1460, not least because this was a time of heighten political turmoil, as I am sure Michael Hicks will also highlight in his lecture. But such an understanding continued well beyond Chaucer’s time and it is worth mentioning that during a further period of turmoil in Henry VIII’s reign, albeit this can be seen as religious as much as political, the Canterbury city authorities sought to clamp down on the activities of a printer living in St Paul’s parish because he had been printing and selling ‘divers and sondry books to divers rude and unlearned people which books be deemed to be in many sentencys clearly against the faith of true Christian men’. At such a point I shall stop, but I thought I would just let you know that the written/printed word, in the form of Early Medieval Kent, 800–1220, is now back with Boydell. The corrected proofs were posted on Wednesday so I’m hopeful it is on track for a mid-summer publication.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Matthew Crockatt

Matthew Crockatt 765

765