Recently on the Sustainability blog, we’ve talked about climate fiction, a subgenre of science fiction that focuses on ecological and environmental change, and can be found in obvious places, like April Doyle’s Hive (2022), or more subtly, such as the metaphor that comes with monster movies like Godzilla (2014) and Pacific Rim (2013).

Today, we’re digging deeper, and we’re talking about solarpunk.

Despite gaining popularity online in 2014, solarpunk was coined in 2008 as a sci-fi subgenre and social movement that envisions the progression of technology alongside the environment. Rather than technology destroying the natural world, or the flourishing environment hindering the progression of technology, the two work hand-in-hand to create an advanced, yet holistic, civilisation. If we’re getting specific, the prefix “solar” refers to solar energy, or renewable energy as a whole, while the suffix “punk” associates the genre with other movements like cyberpunk and steampunk and more mainstream punk rebellion.

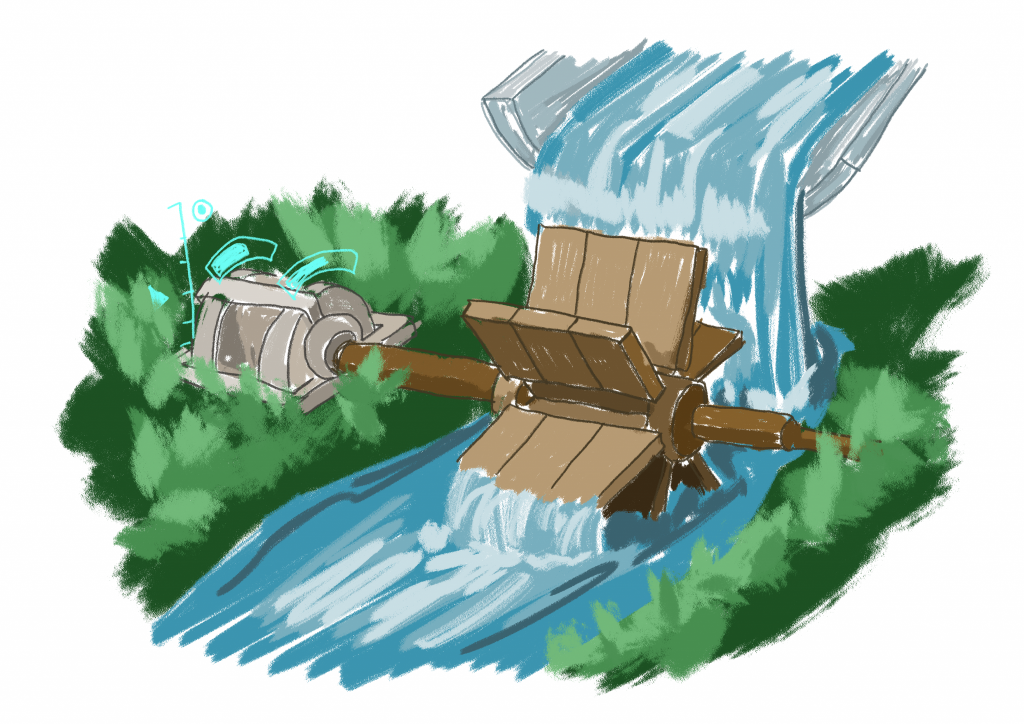

Visually, solarpunk is bright and optimistic; images depict ecological utopias, community living, walkable cities, sprawling plant life, and pointedly, a type of accessible technology akin to analogue. Rather than going hypermodern, with sleek gunmetal grey designs and cold colours associated with classic sci-fi depictions of the future, solarpunk technology is warm, often rounded, and easy to understand. Usable for all people of any age, without a learning curve, the technology exists in the face of the newly-common practice of planned obsolescence – the things that are built in a solarpunk future are built to stand the test of time.

There are four core aspects to the philosophy of solarpunk: renewable energy, refusing pessimism, sustainable technology and a do-it-yourself ethos that supports low-tech ways of living, such as permaculture, gardening, open-source and community-style living. Its imagery is often based in the ornamental Art Nouveau style, with organic linework and earthy tones. The fashion is loose, bright, with a focus on mending and thrifting, while the politics are leftist but rooted in reality. Unlike cyber- and steampunk, which adopt more fictional narratives, solarpunk is a possible reality with potential; the ideals and technology do not need to remain imaginary, and in the face of the very real threat of climate change, solarpunk presents more solutions than flights of fancy.

Despite being almost two decades old, solarpunk novels and films are far and few between. In 2018, Tor Books commissioned Wayfarers writer Becky Chambers to create a solarpunk duology, the result of which being the novellas, A Psalm for the Wild-Built (2021) and its sequel, A Prayer for the Crown-Shy (2022): stories that address overpopulation, oil usage, and the question “What do people need?” Several novels were retroactively assigned to the genre, such as Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home (1985) and Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia (1975). Meanwhile, in a study of the forty-four most popular American science film films, solarpunk was nowhere to be found; nature was all but ignored in visions of the future, depicting pervasive monoculture and domesticated greenery in urban spaces.

Although there are incredibly few films that sit firmly in solarpunk in a purposeful and obvious way, several films can be argued into the genre, such as much of Studio Ghibli’s filmography and aesthetics, and Bong Joon-ho’s Okja (2017), with its anti-capitalist messages and support of a sustainable, low-tech lifestyle. Aspects of other films are also blatantly solarpunk, such as the architectural style of Wakanda in Black Panther (2018): its central city is walkable, with a seemingly robust public transportation system; features greenery heavily and practically while being incredibly advanced technologically, and is built in a way that clearly works for its community. Likewise, there’s arguments for the cities in Zootopia (2016) and Big Hero Six (2014) as solarpunk-inspired, featuring floating wind turbines, community-focused architecture, and positive uses of technology.

Recently, however, we’ve had an outright solarpunk utopia featured in Disney’s Strange World (2022). A film about fathers and sons and generational divides also tells the story of a solarpunk utopia where green energy is created through the use of a farmable plant called Pando, but when the crop starts dying, the community must put together a mission to save their home and their environment.

There are also solarpunk tabletop roleplay games! Independent creators have written adventures such as Lost Eons (2021), about a journey to the surface world after a life in your underground utopian Haven; Green Skies, a solo roleplay and journalling adventure where you play a sentient building in a utopian future; and Roots & Flowers (2021), a solarpunk hack of Lasers and Feelings in which the party tackles issues facing their community.

The ideals of solarpunk have been growing in popularity over the past decade; thrifting and upcycling clothes, visible mending, growing your own food, baking your own bread and urban gardening all growing mainstream attention, especially over the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns. With these values taking root, it has slowly become both fashionable and profitable to co-opt them into marketing, commonly referred to as greenwashing. Most famous is the 2021 Chobani yogurt advert, Dear Alice, depicting a solarpunk utopia, fit with community dining and solutions to farming that look friendly and low-tech. At the end of the advert, the screen reads that this idealistic vision is “brought to you by Chobani”. There is also a trend in creating architectural mock-up images of skyscrapers and urban buildings with plant life façades and green roofs to give the appearance of benefiting nature without addressing the actual environmental issues of such buildings. Solarpunk researcher Adam Flynn refers to these as “fake solarpunk urbanism”.

So, what have we learned?

Here are the takeaways:

- Solarpunk is a genre, art movement and social movement all rolled into one

- Solarpunk is a community-focused, post-capitlist take on renewable energy and do-it-yourself living

- Solarpunk technology is accessible, understandable, and produced ethically with careful resource management

- Solarpunk is a dream, but it is also a possible reality

Want to learn more? Check out the further reading below; a curated list just for you to help you begin your solarpunk journey!

Further reading

- Wakanda – My Dream Solarpunk City

- A Solarpunk Manifesto, based on:

- Adam Flynn’s Solarpunk: Notes towards a manifesto

- Disney’s Strange Solarpunk World

- Solarpunks.net

- Solarpunk: Visions of a just, nature-positive world

- Hopepunk can’t fix our broken science fiction

By Bethany Climpson, Sustainability Engagement Assistant

All images in this blog post are studies of the Chobani advert and drawn digitally by Bethany Climpson.

Sustainability

Sustainability Bethany Climpson

Bethany Climpson 2437

2437