Dr. Joe Hinds, Senior Lecturer at CCCU and practising integrative psychotherapist, discusses the distinction between mental illness and eccentricities, and the appropriateness of mental disorder diagnoses on atypical behaviours.

In 1961 the psychiatrist Thomas Szasz suggested that the concept of mental illness as conceived by the medical profession was vague and unsatisfactory, comparing the assessment of mental disorders with astrology. Indeed, determining the sane from the insane has never been straightforward (Rosenhan, 1973).

Munch’s “The Scream”

Now as then, there is a reliance on prescribed pharmaceuticals to medicate and ‘cure’ people who display out of the ordinary behaviours and beliefs. Where psychiatry once governed, contemporary approaches largely based on psychological rather than psychotherapeutic understandings reinforce the pathologising of experiences. For instance, according to interpretation of the diagnostic criteria of DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), where there was once shyness there is now social anxiety, high-spirited children now have ADHD and where we might observe people with strident differences of opinion we now see them labelled as having conduct disorder. Alongside some appeals against the overtly positive culture in which we are encouraged to participate (“Smile or die” – Ehrenreich, 2009), others have suggested that by strict adherence to the criteria of determining disorders in the DSM (and elsewhere) the concept of happiness is worthy of inclusion as a disorder also.

As a relational psychotherapist, I embrace the simple but important and sometimes difficult arts of listening, empathy, consistency, stillness, and being me in an intimate and emotional therapeutic encounter with another. Interpersonal dynamics, particularly in early life, have much to contribute towards our adult functioning and therefore the role of therapy is to provide a safe and understanding relational space in order to re-address these dynamics. The therapy described here is about demonstrating a genuine humanness and not to hide behind the implementation of techniques or assessment. Why would the person in therapy “Expose their tender under belly if the therapist plays coy and self-protective?” (Whitaker, 1976, p. 329).

In attending to people’s life stories I have found many who have been labelled as having or being something such as borderline personality disorder, bipolar, psychosis, and many others. Whilst undoubtedly these people on occasion may behave in ways that are non-conformist and disconcerting, these behaviours are often the coping strategies (‘symptoms’) of chaotic and often abusive or traumatic life experiences and I am not convinced that categorisation is a necessary nor helpful practice. I have not been tempted to formally evaluate people along any parameter of mental functioning – it is understanding that is needed here not the assessment and removal of symptoms.

“Every human being is born a prince or princess; early experiences convince some that they are frogs, and the rest of the pathological development follows from this” (Berne, 1966, pp. 289-290).

Moreover, the social and cultural conditions of living are increasingly competitive, time pressured, intense, confusing, and, when added to personal experiences of trauma or neglect, may result in increased instances of psychological distress (e.g., 2014 had the highest number [130] of UK adult student suicides: Office for National Statistics). Often the conditions of living are the cause of distress: the ‘problem’ does not necessarily reside within or as part of the individual. In the words of R. D. Laing, the celebrated radical psychiatrist, “Insanity is a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world”.

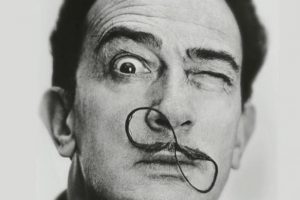

Dali’s “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”

Salvador Dali

The difference between being mad and eccentric, and the acceptance of these in society, is often determined by degree of wealth or success: exemplified by creative genius – see Dali and his The Temptation of Saint Anthony above. The very needy or distressed are not seen as such because of their position in society or their acceptance by favourable sections of the population. Paranoia, narcissism and rigid dichotomous thinking (as indicators or symptoms of distress) displayed by elected world leaders, for instance, would attract the attention of health care professionals under very different circumstances.

Yet these characteristics may also be becoming more prevalent in various societies. Democratically elected leaders are after all voted in by sizable minorities who may recognise, applaud and share those characteristics. In addition, our own habitual practices when set against other cultural standards may not seem to be altogether beneficial or rational including the derogatory categorisation of people according to their level of social conformity. The DSM only completely removed the category of homosexuality (“Sexual Orientation Disturbance”) from the list of disorders in 1987. Therefore it becomes increasingly difficult to separate the so called ‘mentally ill’ from the so called ‘mentally well’.

Key References

Szasz, T. (2011). The myth of mental illness: 50 years later. The Psychiatrist, 35, 179-182.

Whitaker, C. (1976).The hindrance of theory in clinical work. In, P. J. Guerin (Ed.) Family therapy: Theory and practice (pp. 317-329). New York: Gardener Press.

Laing, R. D. (1965). The divided self. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Pelican Books.

Berne E. (1966). Principles of group treatment. New York: Oxford University Press

Rosenhan D. L. et al (1973). On Being Sane in Insane Places. Science, 179, 250-258

Ehrenreich, B. (2010). Smile or Die: How Positive Thinking Fooled America and the World. London: Granta

psychology

psychology Marcus Roberts

Marcus Roberts 1874

1874

Great blog post, Joe! There is a social aspect to this that worries me too: On the one hand, the label itself may do more psychological harm than good, as you say. On the other hand, especially in education, there are (real or apparent) practical advantages to being diagnosed and labelled, such as special arrangements for assessment. How can we break out of this dysfunctional attitude towards mental health?

Dennis

I think that, yes in some cases the label helps bring some sense to our experiencing – makes something abstract become more concrete and therefore understandable. However, my sense is that it’s what we do with that label long term that determines its usefulness. How we respond to people with a diagnosis is problematic (other cultures tend to normalise much that we would deem to be disordered for instance) thus making the label a derogatory device. Again, the tendency is to see the disorder rather than the person – and certainly while there are of course individual components to any behaviour the effect of external environmental factors is underplayed. So, taking the example of dyslexia, while this of course hinders reading etc – it can obscure the persons other abilities (creative, skill or craft based for instance) – there is perhaps a social desirability or expectation that everyone will attain a similar reading ability. We wouldn’t diagnose someone with having a deficit of not seeing in 3D which is typically a skill that many people with dyslexia have.

Best wishes

Joe