Today, 22nd June, is Windrush Day. Introduced in 2018 on the 70th anniversary of the docking of the ship HMT Empire Windrush in Essex, Windrush Day commemorates and celebrates postwar immigration to the UK from the Caribbean. In light of current conversations about race, racism, and the Black Lives Matter movement, which has seen protests centred in Brixton’s Windrush Square, it remains vital to tell and understand the Windrush story. Though frequently mistreated and maligned by the country they chose to call home, black immigrants from the West Indies have enriched this country in every respect. The following blog was originally published as part of CCCU Library’s celebrations for Black History Month 2019 and its messages remain relevant.

October is Black History Month in the UK and this year, the central campaign theme is the celebration of Black women whose impact on British society since the arrival of the West Indian population known as the Windrush generation has been invaluable. As members of families and communities, contributors to vital public services, and forces for progression and change, these women, along with the men and children that accompanied and settled with them, have become an integral part of the country’s DNA since they made the UK their home. In light of the scandal that recently has engulfed Windrush in the media and highlighted the mistreatment by the Home Office of so many of those that were born British subjects and made the journey across the seas, it seems especially important that their importance in Britain is recognised and that they are venerated as they should be.

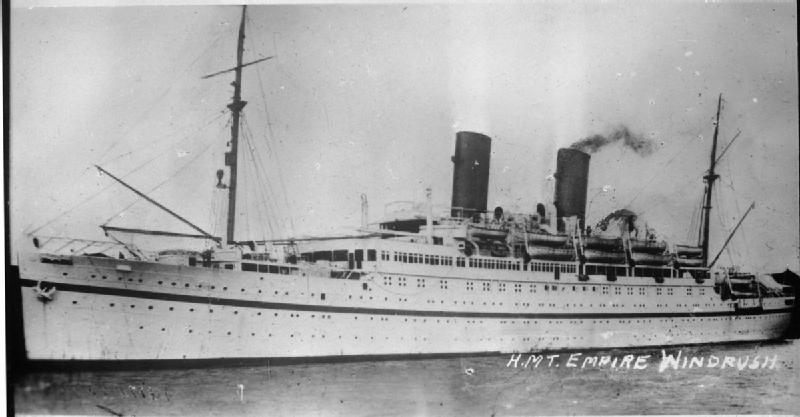

‘Passenger Opportunity to United Kingdom’

The ship HMT Empire Windrush, which landed in Tilbury in June 1948, was one of the first to come to these shores carrying hundreds of passengers from the Caribbean in the aftermath of the Second World War, after an advert appeared in a Jamaican newspaper offering cheap transport to anyone who wanted to find work in post-war Britain, of which there was no shortage. Some on the ship were servicemen taking leave from duty, some were former servicemen who hoped to re-join the British armed forces, and some were people living in Britain’s then colonies in the West Indies who wanted to see what prospects were like in the ‘mother country’. Although significant numbers of West Indians were already present in the UK following the First World War, photographs of Windrush passengers disembarking from the gangplank and setting foot in England have come to be seen as powerful representations of the beginning of a newer, more multicultural era.

Photograph from Wikipedia.

Photograph from Financial Times © Popperfoto/Getty Images.

On Thee Our Hopes We Fix

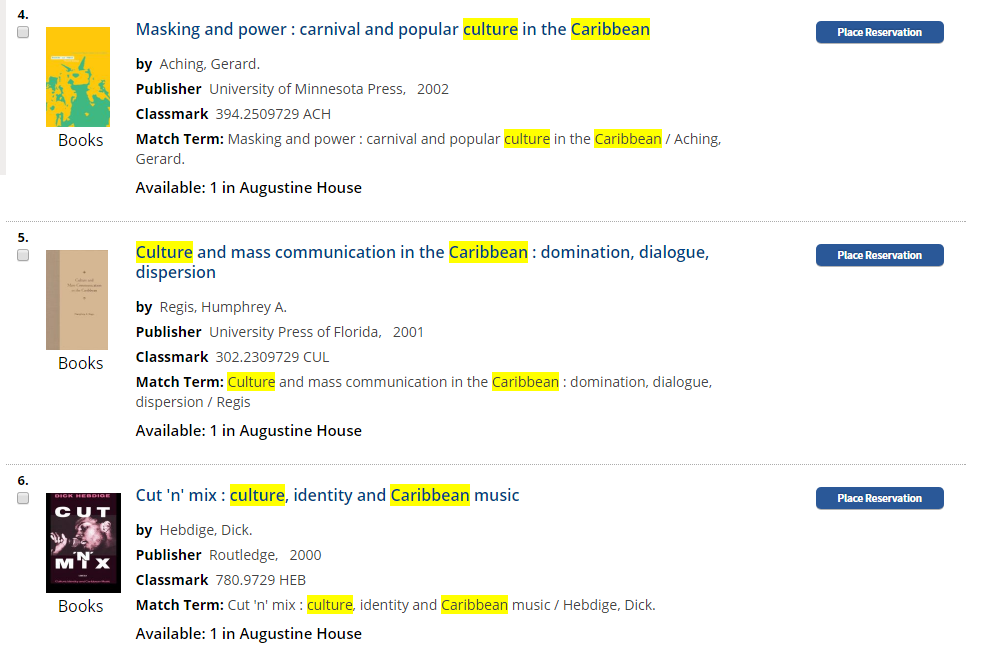

Although the immigration journey made by these passengers and the passengers of other such ships had been encouraged by the UK government, and many members of the Windrush generation helped to fill the labour shortage in industries and services such as British Rail, public transport, and the NHS after the losses of war, those who arrived faced racist prejudice and discrimination, barred from many aspects of public life and rejected by an intolerant white public. Immigration from the Caribbean was mostly stemmed some years later as the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act and 1971 Immigration Act restricted the entry conditions for those wanting to move to the UK but by this point there existed a whole generation of Black Britons with African-Caribbean heritage contributing to British society at every level. People migrating from Commonwealth countries brought not only labour for industry but also a culture that in itself is richly diverse, a melting pot of Calypso music, creole languages and food, and varied religious and spiritual beliefs. If you would like to know more about Caribbean culture, there are several books in the library collection that may be of interest, as shown here from a simple keyword search on LibrarySearch:

As a result of European colonisation, forced migration of slaves from West Africa, and the arrival of merchants and indentured labourers from other parts of the world such as the Middle East, China, and India, the Caribbean islands and their inhabitants both present and former have a wide-ranging history and heritage quite unlike any other place on earth. Capitalising on this diversity with an approach of divide and rule, British Imperial colonisers had created and imposed a strict hierarchy of skin colour, classifying shades and equating them to class and worth. In her essay ‘Back to My Own Country’, writer Andrea Levy describes her light-skinned parents growing up middle class in Jamaica, in large houses and with good jobs, and then finding themselves poor and working class, isolated and belittled in Britain, a country they had learned about in school as a fabled motherland. White Brits did not necessarily have the same tendency towards colourism but it was this blanket racist mistreatment, alongside the shared experience of employment by organisations such as London Transport and the NHS, which helped to forge a shared united identity among Caribbean immigrants who came from a range of different islands and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Photograph from Buzzfeed Meager / Getty Images.

Andrea Levy’s best known novel, the prize-winning Small Island, explores the experiences of those that emigrated as part of the Windrush generation. The novel was adapted into a miniseries, which you can watch through Box of Broadcasts Small Island (Miniseries) · BoB (learningonscreen.ac.uk). You’ll need to login with your University account to access the service. To find out more about Box of Broadcasts take a look at our guide.

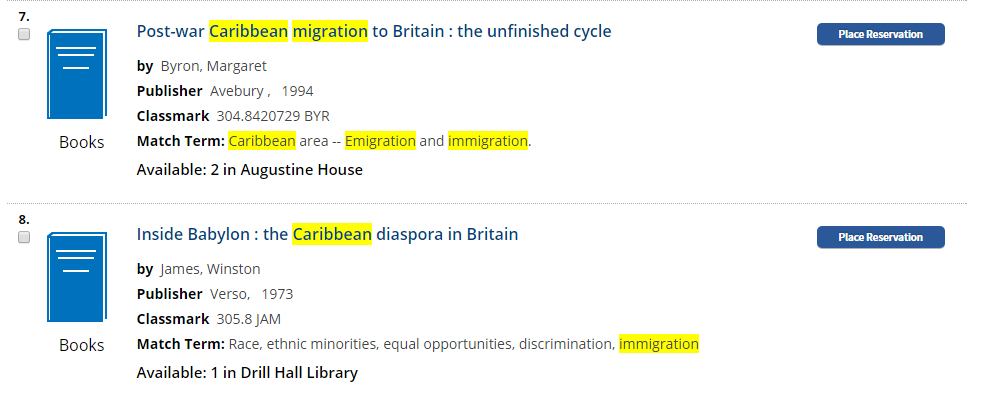

If you are keen to learn more about this period of recent British history, there are a number of books in the CCCU library collection that explore the history of West Indian immigration and its impact on the UK, for example these titles:

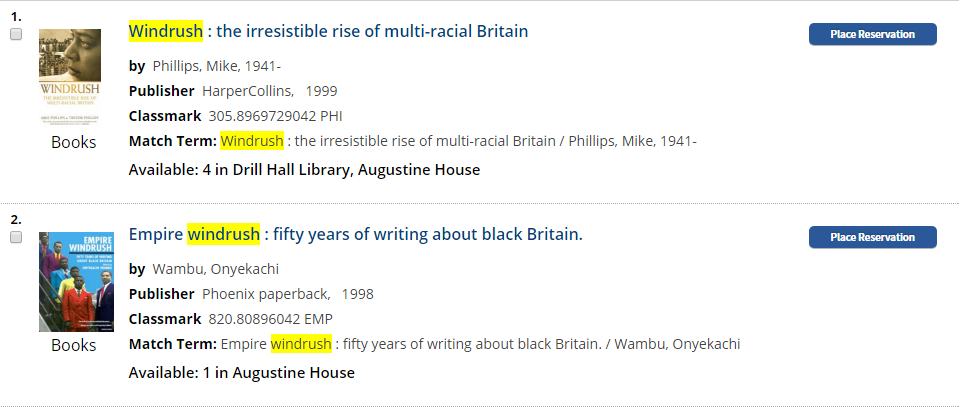

And there are two books that focus on Windrush in particular:

Rivers of Blood

In reaction to the abuse directed at Britain’s populations of colour, the Government introduced the Race Relations Acts 1965 and 1968, legislation which outlawed racial discrimination and meant that housing, employment, and public services could no longer legally be refused on grounds of skin colour or ethnicity. The latter bill was the focus of Conservative MP Enoch Powell’s speech in Birmingham, often referred to as the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech whereby he condemned mass immigration and expressed fear regarding what he perceived as the replacement of the UK’s native white population. Powell was dismissed from Edward Heath’s Shadow Cabinet the day after giving his address but his words were illustrative of the deep divide and tensions that existed between white Brits and immigrants of colour, and the rejection and animosity felt by West Indians and other non-white citizens living in the UK.

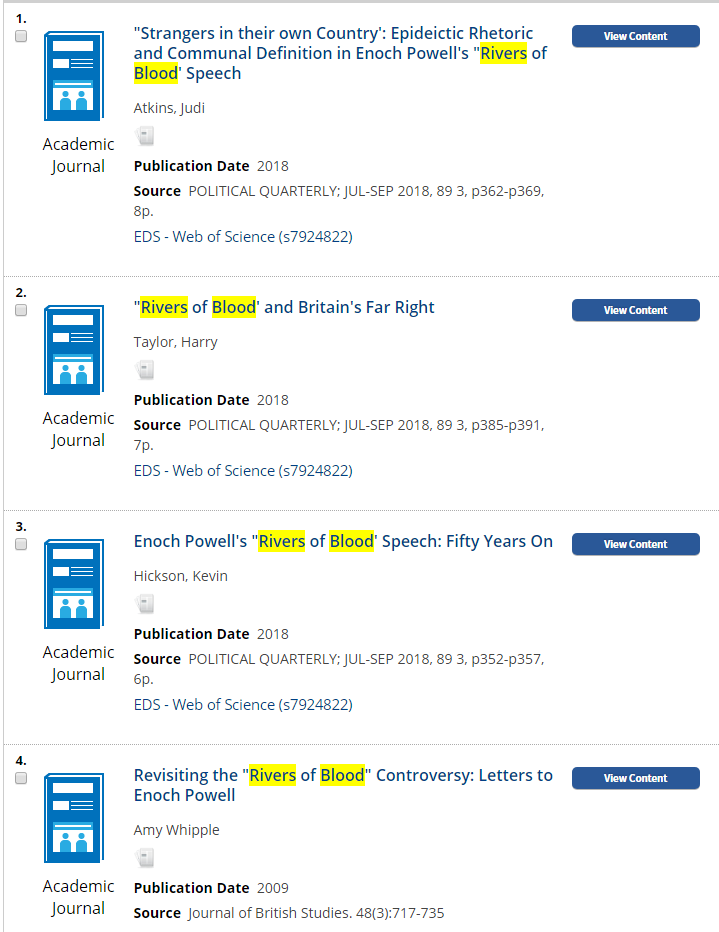

There are a number of online journal articles you can access through LibrarySearch about Powell’s speech, its impact, and its legacy. A quick search for ‘rivers of blood’ returns a large number of results, a snippet of which you can see here:

The Scandal of a Generation

The generation of immigrants that came from the West Indies to Britain decades ago, and the generations that have followed, have helped create this wonderfully diverse and multicultural nation, making the Home Office scandal uncovered last year an all the more appalling series of legal and human rights violations. Seemingly linked to the ‘hostile environment’ policy implemented by Theresa May during her tenure as Home Secretary, it became apparent that a large number of long-term UK residents who had arrived in the Windrush era had been wrongly detained, denied benefits and care to which they were entitled, wrongly denied re-entry to the UK, threatened with deportation, and in scores of cases wrongly deported. If you would like to read some of the many newspaper articles that covered the scandal, you can do so through LexisLibrary Newspapers UK, a database that allows you to search huge numbers of publications.

The Home Office neither kept a record of those granted leave to remain nor issued any paperwork confirming their status and this, in addition to the fact that many of the Windrush generation arrived as children on their parents’ passports, and that landing cards belonging to the migrants were destroyed by the Home Office in 2010, has made it very difficult for a large number of them to provide evidence of their right to stay and live in the UK. The Home Affairs Select Committee produced a critical report in 2018 which condemned the culture in which this unfair treatment had thrived and warned that unless significant changes were made, the same mistakes would be made again. The report found that there were a number of questions which the Home Office was unable, or unwilling, to answer, and access was not granted to internal paperwork. It remains to be seen whether the recommendations made by the report, including a reassessment of the efficacy, fairness, and impact of all hostile environment policies, and an extension of the government’s compensation scheme to account not only for financial hardship caused by the government’s failings but also the emotional burden endured, will be acted upon.

Not In This Land Alone

One can only hope that the mistakes of the Windrush scandal are not repeated. We can and should focus on the abundant positives brought by immigration and the introduction between cultures. Imagine Notting Hill without carnival. Imagine there being no UK high streets with the heady aromas of Caribbean cooking. Imagine a UK music scene uninfluenced by the liveliness and direct social commentary of Calypso. And imagine a national health service or rail network not having been staffed in their time of need by immigrant workers making huge contributions to the nation they now called home. This Black History Month these Black Britons are honoured and celebrated, and their achievements recognised. Windrush is a word that evokes notions of courage, hope, adversity, diversity, oppression, and wrongdoing. All of these are important elements of the story. And it’s a story that needs to be told for generations to come.

Library

Library Emma Latham

Emma Latham 1972

1972