I thought I would provide a final reminder about events in the first week of July, before coming to the AMARC conference on Monday and Jason’s presentation to the Kent History Postgraduates group on Wednesday.

On the Tuesday, we are having a preliminary meeting at Christ Church involving staff from history and archaeology, experts on the built history of Sandwich and Richborough and those interested in seeing how these places could be placed more firmly at the forefront of national, and international heritage places. It is an interesting idea and it will be fascinating to see how this project develops.

Then on Thursday it is the monthly meeting of the Lossenham Project wills group, which is one of the in-person meetings. This time rather than having our meeting at Lossenham, Sue Hatt, one of the group, will be leading us on a guided tour of Tenterden Museum and its exhibition. Sue has been very heavily involved in the creation of much of the exhibition and materials from the research conducted by the wills group has been used to do this. So, another very exciting project that offers excellent potential in terms of knowledge exchange and outreach, as well as impact. Consequently, it will be interesting to find out what level and type of response there has been to the exhibition.

Moving to the Saturday there are two events, firstly during the day there will be the annual Medieval Pageant which with its giants will be processing through the city from the Westgate Towers. This will be followed in the afternoon by the Family Trail across the city, using such places as many of the churches – from St Dunstan’s in the north-west to St Martin’s in the south-east. Another of these churches will be St Paul’s, which is where the CKHH will be based, and we’ll be offering young pageant goers and their families the opportunity to craft their own animal facemasks and paper plate unicorn horns. This is the official website, so please do check it out: https://canterburymedievalpageant.co.uk/

The second event is the St Thomas More Commemoration Service at St Dunstan’s church at 7.30pm. This annual event on the anniversary of the day More was beheaded is marked by a commemorative civic service, which is attended by the Lord Mayor, local Catholic clergy and members of the legal profession, as well as parishioners and members of the public – all welcome, refreshments after the service. The service includes an address and last year the guest speaker was Dr David Rundle, a specialist in the Renaissance in England at the University of Kent. His subject was ‘From St Dunstan to Thomas More: Canterbury, learning and sanctity’, whereas this year I’ll be giving it under the title ‘Thomas More’s Canterbury’, and while it will consider the 1520s, I have decided to narrow it down further to make use of a fortunate coincidence.

And an advance notice, the Brook Rural Museum with which we have a strong association, will be holding their second ‘Medieval Fayre’ on Saturday 13 July, 10am to 3pm. This will include a wide range of demonstrations and drop-in activities for all ages, as well as the wonderful late 14th-century barn, the early round 19th-century oast house and the collection of historic farming implements – from hand tools to ploughs and carts. Entry is £5, children under 14 go free. For more details, see: https://brookruralmuseum.org.uk/

Now to the reports for this week and therefore I’ll start with the Association for Manuscripts and Archives in Research Collections (AMARC) summer meeting and AGM that took place at the International Study Centre within the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral. Dr James Freeman, Medieval Manuscripts Specialist from Cambridge and the AMARC chairman, welcomed everyone to the meeting and then having introduced Dr Robert Gallagher, the first speaker from the University of Kent, Rob began his presentation on ‘Anglo-Saxon charters’. As he said in his introduction, looking at the time before the Norman Conquest by far the greatest documentary sources for this early medieval period are charters, albeit the term ‘charter’ in England at least has been employed to cover several different types of documents, and therefore can be seen as a somewhat vague term. For beyond the royal diplomas that were drawn up to mark the transfer of land from the king to an individual or (religious) institution, other document forms categorised as ‘charters’ by Peter Sawyer for his Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography include wills, leases, documents covering disputes, writs and letters. This means the printed version and today the Electronic Sawyer contain details of over 1,500 documents, each with its own ‘S’ number. Not that these are all authentic concerning the details they contain, and the role of forgeries is an old one, including some produced in the early 9th century but purporting to be from an earlier date.

Rob had decided to talk about three main groups: the earlies surviving royal diplomas; those from the mid-9th century which while being more diverse, do provide evidence for a more centralised royal bureaucracy, where the writing of these royal diplomas was no longer solely executed by local priests. His third topic comprised the considerable expansion in the production of documents and the use of Old English rather than also wholly Latin. He also made another several general points: that such diplomas include the date which means they can be used as markers regarding other documents. Secondly, the English typology is different to that of their Frankish counterpoints in that all the English ones include witness lists, and therefore the power of the assemblies where such agreements were made, whereas this only applies to the private transactions in the Frankish sources. Thirdly the differing use of languages, and whereas in the early centuries they were in Latin, the role and importance of Old English in clear from the late Anglo-Saxon period up to 1070.

Rob then discussed examples from each of his three sections. As he noted the earliest surviving charter is dated AD 679 and concerns a donation of land by Hlothhere king of Kent to the religious house at Reculver. Even though it is a small single sheet, its survival as a document rather than one copied into a later cartulary underlines its importance, for it is an indicator of the value placed on the written word and of the Church vis-à-vis the king and his kingdom. Building on this and taking an 11th-century charter of King Athelstan, Rob highlighted the ‘classic’ elements such documents contain to illustrate how formulaic they are: the invocation to God and the proem; the identities of donor and recipient; the nature of the holding including boundary clauses in Old English; the spiritual blessing/sanction if not adhered to; the dating clause, and the sometimes very extensive witness list.

In addition to these single sheets, Rob explored the role of the chirograph, where two (or three) copies were made on the same sheet with the work ‘chirograph’ between them such that it could be cut and a section given to the interested parties with the third as a record (see feet of fines and indentures) and by bringing them together again, each section could be authenticated.

To finish, Rob discussed the survival and importance of early cartularies, before noting which are the major archives for Anglo-Saxon charters, Canterbury being one of these, as well as some of its most important holdings. We were fortunate to see a few of these documents when we visited the Cathedral Archives & Library after lunch.

The audience showed their appreciation and after a few questions, James introduced Dr David Rundle, also from the University of Kent who spoke on ‘Where have all the Manuscripts gone? Lost and Half-Lost Codices from Canterbury Cathedral Priory’. As you would expect, David opened with a clever comment that medieval commentators would have seen it as only appropriate that those who broke up manuscripts should be condemned to hell; yet for those working on such manuscripts today, it would be better instead to thanks such people rather than condemn them because in many cases these fragments are the only remains we have left of certain manuscripts.

Taking this as his starting point, David pointed out that for much of period between the 13th and 15th century, that is until late in that century when Oxford probably took on the position, Canterbury with its two great Benedictine houses probably had the greatest collection of books in England. For we have Prior Eastry’s catalogue of 1831 books at the cathedral priory for the early 14th century and by the dissolution this collection stood at over 2,200 manuscripts relating to the library. However, in terms of the survival of this library it is not good at 16% when compared to Peterhouse, Cambridge at 55.7%, but then neither is it as catastrophic as at King’s Cambridge where the loss amounts to 98/9%.

The next question David posed was where are they? Are they still at their ‘home’ institution or have the survivors found themselves carted off elsewhere, either as part of a consignment or as individual manuscripts in more of a dripping away of Canterbury Cathedral New Foundation’s book collection. The answer being that many have gone – there were 25 manuscripts in situ in 1630, and today the cathedral library holds 29 complete manuscripts, and while, yes, Archbishops Matthew Parker and John Whitgift did see to the removing of Canterbury materials to their respective university colleges, if they hadn’t might even more have dripped away to become untraceable in many cases.

Furthermore, David was keen to point out that even though there was this acceleration of losses/movements post-Dissolution, the concept of breaking up manuscripts for reuse was far from alien in a monastic library. For books got old and needed repairs, whether undertaken in the monastery itself or carried out by bookbinders known to have been resident in late 15th-century Canterbury, or might be superseded by a new copy, and there was also the movement of books between Canterbury and the priory’s college at Oxford. What might be seen as this porosity and fluidity was part of the life of the library, and its continuation, albeit more extreme, during the reigns of all the later Tudor monarchs, including Mary, can be seen to have ‘saved’ a good number of fragments. Moreover, David was keen to explain that how this had been done is important, as well as that this process continued right up to 1599 – there were still manuscripts available for such dismantling, they hadn’t all gone! Among the re-uses David has been investigating are flyleaves and wrappers, and these have revealed some interesting ideas. Perhaps the most important is that those doing this work did not cut the text, rather they removed the margins and even where a better fit might have involved cutting off written sections, they didn’t do it. This David sees as one way that those of the New Foundation sought to safeguard some part of their inheritance, an inheritance that conceptually, at least, stretched back to Augustine in 697 and therefore their actions such be viewed as having “lovingly reused” some of the cathedral priory’s medieval manuscripts.

David’s presentation similarly drew enthusiastic applause and there followed an interesting discussion in response to several questions from the audience. We then broke for lunch before the Association’s AGM and thereafter the attendees were guided on tours of the archives and library by Cressida Williams and Fawn Todd respectively. These everyone enjoyed and we then reconvened for the final two presentations.

For the first, I figuratively took the audience out of the monastic precincts and into the city to explore ‘The pre-modern records for the city of Canterbury’. The medieval and early modern historian of Canterbury is very fortunate because of the richness of the surviving sources. Ok, yes there have been losses over the centuries, but within the corporation’s own archive there is a remarkable survival from the mid 13th century that Dr John Williams, following William Urry, has employed to show the considerable level of self-governance that the city had gained by this period. Furthermore, charter evidence can push this back even further, possibly to the late 11th century. These first city records are the bailiffs accounts for part of the years 1256-7 and show that the city was raising money to pay the fee farm to the Crown from such sources as tolls on strangers’ horses and packs, woad and onions. The income through the burghmote court was similarly varied, including debt recovery, trespass, the selling of sub-standard bread and stallage. Expenditure was similarly noted and the stipend for the clerk, for instance, highlights the professionalisation of such early civic record keeping.

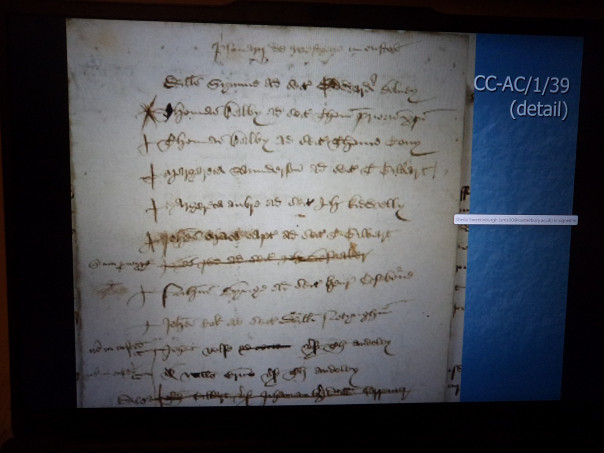

Moving on I next outlined the coverage of civic record keeping from the 14th century onwards (administrative, financial, judicial, those produced by another eg royal charters), as well as the range of physical forms such records could take. Thereafter having listed the 15 or so categories of medieval record held at Canterbury Cathedral Archives within the civic collections, I went through showing examples of many of these, including such survivals as a list of prisoners in the city’s jail at Westgate from c.1500.

For here, I’ll just mention a couple from the late 14th century because they similarly illustrate how records can ‘talk to each other’ and such record linkage is an extremely valuable tool. To start, I discussed the great chamberlains’ account books that offer details on civic office holders, those leasing the king’s mill, the name, ward of residence and often the occupation of annual licenced traders/artisans, the names and other details relating to new freemen (by birth, marriage, redemption), fish and flesh stall holders, those renting civic property and those involved in some way within the details concerning the chamberlains’ expenses. To such varied documents can be added the books containing copies of late 14th-century spoken wills proved in the burghmote because they reference freehold property within the liberty, as well as cases from the city’s petty sessions. Just as an aside, if you go outside the civic archives there are, of course, the poll tax records. If we return to the city archives, the records listed above are in the form of books, rolls and single sheets, which reflects my final slide where I listed the varied ways historians can use such records, albeit they can be broadly divided into two sections: exploring the documents themselves as material culture and secondly using the information they contain.

This worked well and led on nicely to the final presentation by Dr David Shaw, now retired from the University of Kent, whose presentation was entitled ‘Printed ephemera in the archive collections’. For as David said, having for many years worked on the cathedral’s pre-1801 printed books collection in the library, he has recently turned his attention to the printed materials found in the archive. This has proved to be a fruitful and interesting enterprise and has meant that he has added to and emended entries on the STC database, which is helpful in and of itself.

Among the printed items David mentioned were printed royal proclamations, large folio Bibles, including a strangely large collection of five Baskerville Bibles of the 1763 edition. Three of these came into the archives as part of parish collections and he can trace the provenance of the other two as well. There are also examples of what had been chained books in their home parish, such as a copy to Foxe’s Acts and Monuments from 1570, donated by a previous lady mayoress of New Romney from an unknown Romney Marsh parish. This is an extremely delicate item, but the chain still looks remarkably robust!

A far more substantial book is the 1533 Book of Statutes which the city corporation deposited in the archives in 1884, while the single sheet folded as an octavo to form a pocket almanac, from 1644, is far less so. However, this was not intended for longevity and its chance survival demonstrates just that. From David’s perspective one of the key issues is that it highlights the presence and activities of printers in the city, as does similarly a handbill for the Canterbury races – from the Hales family estate papers. He then discussed several other handbills that he has researched concerning the light that they throw of provincial printers, local commerce and the life of the city.

More recently, David has turned his attention to settlement certificates, the printed blank forms issued by overseers of the poor and churchwardens that were filled in with the name and other details of those seeking entitlement to parish poor relief. As David said he is interested in the role of the Stationers in the production of these forms, and he has an article on this in the journal Publishing History (2023).

This presentation, too, was warmly received and to finish the day, James thanked all the speakers and Cressida and her team at Canterbury Cathedral Archives for hosting the day, the enthusiastic audience, and said it would be excellent to expand AMARC’s membership by attracting more student members as well as others interested in archives but who may not be involved in such institutions professionally. If you feel this might be for you, please do check out the website: https://amarcsite.wordpress.com/

Now to the second research event of the week, Jason Mazzocchi’s presentation to the Kent History Postgraduates group in person and online. Due to some room issues, we found ourselves in Anselm and after some technical difficulties we were able to see how Jason has started to investigate the Court of Exchequer case involving the Company of the Fisherman and Dredgermen of Faversham as the plaintiffs in this case. The defendants were fishermen from Milton but one of the points Jason was making was that these were not solely fishermen, rather men of those from Faversham were leading members of the town, were prosperous individuals, had mercantile interests and were part of networks that encompassed far more than Faversham and its environs for they extended to London and even overseas.

As well as taking the group (in person and online) through the processes involved in this case, Jason was keen to stress how both sides used certain ideas that were expressed in specific ways which would have been understood by both sides, the court officials, and were also intended for other audiences, yes contemporaries but equally for those in the future – they were writing the history of the town using specific vocabulary, by referring to certain events in the past, by underlining their care and concern for named groups (the fishermen) within the local community and the justice of their cause (endorsed by the court’s decision).

In addition to the value those from Faversham and also from Milton (and from Essex) placed on the written word and court procedures, Jason was keen to draw attention to the way places and their spatial dynamics were deployed by both sides, including the disputed use of named oyster grounds and the adjacent (common) channel that was used by shipping, not just the oystermen. These spatial politics were articulated through words – the recorded perambulation, but equally were portrayed on plans of the estuary with its creeks and oyster grounds.

Having taken his audience through the case, including highlighting certain aspects from the depositions of plaintiffs and defendants to illustrate differences and similarities of both the type of men called to the court and their testimony, Jason drew a number of preliminary conclusions before opening the seminar up for discussion. This drew several comments, questions and ideas, not least Lizzie’s thought about the arena of emotions and how the court might be said to have given both sides such a space. Indeed, the discussion continued over tea afterwards, again marking a highly successful session, and in July it is excellent that Dr Janet Clayton with focus on the early involvement of the Walsingham family at Scadbury.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1786

1786