Just to say that I have now found the fifth lost blog and therefore it gives me great pleasure to bring back in some form the blog written by Dr Diane Heath and Caz Heath. Consequently, Skin and Bone, Wood and Stone – Round 2!

It is with great pleasure that I (Diane) introduce the following blogpost on the Medieval Animals Heritage Conference that ran from Wednesday 28 June to Saturday 1 July, written by CCCU Creative Writing alumna, Caz.

First, of all, many thanks indeed to everyone involved in the Conference, especially our speakers, delegates, and our terrific Welcome Team of CCCU postgrads, graduands, and undergrads, Jason Mazziocchi, Peter Joyce, Keiron Hoyle (with a special shout out to Benedict who made all the Hedgehog logo keyrings presented to our speakers), Harry Munday, Jane Joyce, Eli Salter, and of course, Caz Heath (complete transparency – I am a proud mum) I was touched to receive and greatly appreciated the support of colleagues attending and participating in the Conference including Stefania Ciocia, Claire Bartram, Dave Budgen, Maria Diemling, Pip Gregory, Annette King, Sonia Overall, Astrid Stilma, Sheila Sweetinburgh, and Ellie Williams. It was great to see MAH volunteers in the audience (and in the case of Laine Bloxham, speaking), including some of the fantastic Beastly Latin team, the wonderful artists Penny Bernard and Alex le Rossignol who also gave artworks for the exhibition with Clelia Scala. Thank you too to Curator Craig Bowen of The Beaney for kindly allowing us to visit the Learning Lab during the Conference and indeed for allowing our SEND children to become Young Curators with a Pop-up Exhibition Showcase for the Medieval Animals Heritage Project and the Canterbury Medieval Pageant. Thanks – again — to the utterly kind and generous Cressida Williams and her team Fay and Daniel, for the wonderful Archival exhibition of medieval and early modern manuscripts, charters and books. I so appreciated our postgraduate attendees giving up their time to come to the conference, together with members of the public, for this was an open conference, in keeping with the project and National Lottery Heritage Fund’s remit of inclusivity and wellbeing. My thanks too go to the Hospitality team for oodles of delicious food, Toby Charlton-Taylor for AV support, Ursula Harris for sorting out air-conditioning problems on the eve of the conference (phew), all our great admin team – Lisa, Sarah and Joe, Ethan Basso for helping our speakers with their accommodation needs so speedily, and to Howie and the moving team for the putting up the exhibition and for helping to install the pinball and 1962 vintage princess jukebox with all the animal title songs put together by my patient partner, Pete.

Report on the second half of the Medieval Animals Heritage Conference by Caz.

I was fortunate enough to be able to attend the Skin and Bone, Wood and Stone conference on medieval animals. Despite being very much a lay person where medieval history and medievalism are concerned, the papers were all fascinating and accessible even when discussing esoteric subject matter. From the writings of Aristotle to Byzantine relics to a 1970s manual of ghosts, the speakers covered a vast range of topics in an engaging, exciting, and informative manner.

The conference began with a reading from Dr. Sonia Overall of a selection of her poems. The underlying theme of the selections was the idea of water as both a liminal space and also as a place of refuge away from humanity and human society. These were particularly well-drawn in two of her poems, on the Water-Wose of Orford and middle-aged swimmers respectively. In the case of the former, the shifting presence and absence of water, told in a way that flowed like a tide under the moon, was an elegant metaphor for the power of society to isolate and other those who approach life in ways different to the norm. It contrasted with the latter poem, which was a celebration of water as a space to be free of social and societal pressures wherein the subject of the poem felt no longer bound by the judgemental standards of the landed world.

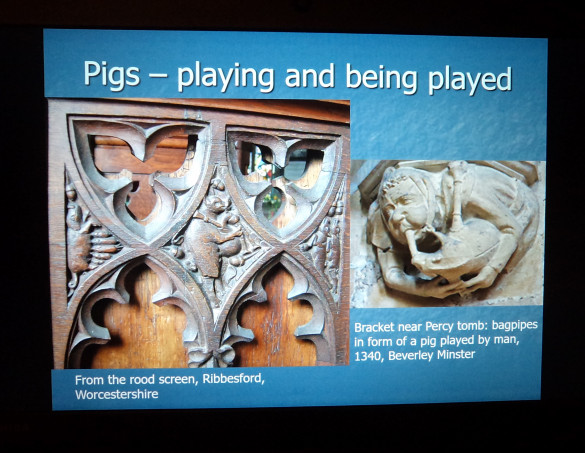

The first evening of the conference concluded with a lecture from Dr. Sheila Sweetinburgh on the role of the pig in medieval society and culture. Dr. Sweetinburgh’s paper demonstrated the value of pigs to all walks of medieval life, not just as a food source but as a vital and prominent piece of working-class cultural heritage. Medieval depictions of pigs within artefacts such as the Ribbesford rood screen depict a pig whose image is not the one-dimensional one lay persons like me might assume was the case, but whose cultural power and ubiquity was expressed through tactile material methods.

The following morning kicked off in high Victorian style with Martin Crowther (MAH Project Manager and Maison Dieu, Dover’s Engagement Officer). Martin discussed the medieval animals depicted in the astonishing Maison Dieu, a medieval building that became Dover’s nineteenth-century Town Hall that is now being restored by National Lottery Heritage Fund. in the secular stained glass by Edward Pointer – for example the small blue dragon landing on a knight’s helmet, and in the decorative programme of architect William Burgess – full of lions and poppinjays (parrots – Burgess’s signature avian symbol), the medieval animals interpreted in Victorian Gothic sprang to life in Martin’s talk in a feast of colour and opulence.

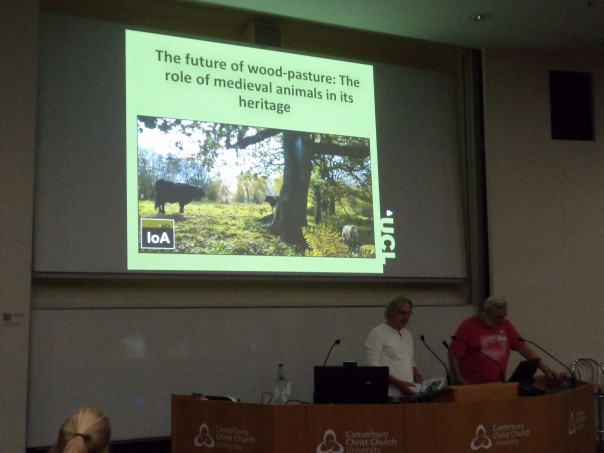

The materiality of the Maison Dieu’s Stone Hall was contrasted by the next speaker’s emphasis on wood – as in woodland pasture. Dr Andy Margetts’ paper on restoring and future-proofing these vital biodiverse medieval landscapes resonated with Sheila Sweetinburgh’s paper on pigs feeding on acorns and nuts in medieval wood pastures. Andy traced key elements of wood pasture – the open spaces, the variety of trees, and the importance of the grubbing up by feeding pigs – to demonstrate how this quintessential medieval landuse could aid farmers face the climate emergency.

Our final first panellist was Dr Catriona Cooper, also like Andy an archaeologist – and concerned with heritage futures as well as heritage pasts. Her interest in digital humanities led Cat to become a friend to the project and come to the V&A to scan a large (think paving slab) medieval alabaster altarpiece fragment depicting St Thomas Becket. The scan was created and reimagined in a gypsum compound to echo the tactility of the original soft alabaster stone by Steve Dey of ThinkSee3D. SEND children handled it following their performances in the Becket Play last summer, embedding memories through touch. Catriona had the gypsum artefact circulated around the audience and many commented on its weight, the beautiful gypsum soft finish and the detail. The next step is to make smaller scale keepsakes for the children for painting and keeping, and to distribute artists’ versions to churches that have connections with St Thomas Becket. The panellists spoke with detailed eloquence on the very varied aspects of medieval animal cultural heritage management.

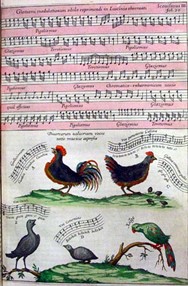

The second panel of the conference had an avian theme – but with two very different takes on early modern birds. Duncan Frost began the panel with his paper on songbirds – and how several handbooks published in this period taught people how to train their pet songbirds to learn specific tunes, or even sing songs from other bird species. The songbird’s remarkable mimicry was held up as an exemplum of the ideal student and this remarkable skill was then used to interrogate human/animal boundaries. Duncan’s richly observed paper reminded me of the delights of a hand-coloured edition of Kirchener’s 1650 Musurgia Universalis with its musical annotations of birdsong in Glasgow University Library (Sp Coll Ferguson Af-x.9 & Af-x.10) and as it includes the chicken’s song, that provides a visual link to Meeley’s paper.

This idea of materiality was expressed further by Amelia Doherty in her interesting and well-argued paper on the material culture surrounding the chicken during the Early Modern period. She described the materiality of the chicken both through their presence and absence in depictions of the chicken in this period. On the one hand, we have what she described as “the silences”: the absence of chickens as things listed in probate inventories; the idea that chicken thieves rarely feature in court records; and so on. On the other, there is their material presence through depictions of fighting cocks and in the chicken ornaments of 1740s chinoiserie.

After a brief break for refreshments, we were treated to a superb presentation by Mark Summers of the University of Arkansas Fayetteville on the role of the ostrich egg in the origins of medieval empiricism and what the paper called the “foundation of knowledge”. It was an opportunity to learn about the materiality of the ostrich egg and its connections to high medieval scientists and the development of the scientific method, especially via Albertus Magnus and his note that feeding iron to ostriches was unsuccessful. The beauty of the eggs decorated and used as reliquaries was breath-taking. The conference also provided an opportunity for Dr Summers himself, as — thanks to the conference’s accompanying exhibition — he was able to hold a real ostrich egg for the first time.

Mark’s paper was followed by two papers on dragons. Nadia Mariana Consiglieri spoke on the materiality of dragon paintings that used lizard and crocodile skin, teeth and skulls to enhance the dragon as both a symbol and as some form of real animal. Not only that but casts of animal specimens were also used to make these creatures credible protagonists for their saintly foes. This was a paper full of insights into how to make a dragon.

Cecily Hughes brought the panel to a close with her equally riveting study of a walrus ivory lectern or stool finial of a small, fanged dragonhead. Posited as a Viking and pagan theme in a Christian context, redolent of Beowulf’s dragon, this tantalising object seemed defeated yet lived on in the medieval and indeed our own cultural heritage. The comparison of another dragonhead ivory – this with a fine Norman moustache was a real eye-opener.

Away from materiality to the fabled – we turned to our final panel of the day, ‘Howl’ which interrogated changing ideas of the werewolf from Dr Vicki Blud’s medieval Melion as ‘un/dressed to kill’ to early modern werewolf trials investigated as animal/human biographies by Todd Simmons to Gothic horror heritage commercialisation by Dr David Budgen.

The Conference then broke for the Beaney SEND showcase and the conference dinner at Chapter and some of us made it to the Two Sawyers pub afterwards.

The early morning saw a slight change to the programme and our first panel had three papers. Exploring human/Animal borders threw up some fascinating juxtapositions, as Kathryn Smithies’ paper showed the medieval fabliau humour at the death and burial of a donkey in consecrated ground – a human end to an ass’s life. Whereas Adriana Gallardo Luque demonstrated how an examplum on the Unicorn revealed the creature was perceived as an allegory of human death. In between Sven Gins spoke on how the Lion – and other animals were understood as aspects of being lion-like with the implicit assumptions on bravery and kingship we still refer to today.

After a break for refreshments on Friday morning, Dr Pip Gregory gave a fascinating paper comparing and contrasting the meanings of animals within medieval bestiaries and 19th-20th century political cartoons. One point that illustrated how things have changed was her analysis of birds within the presentation, comparing the relatively undetailed depictions of medieval birds with strong identifying stories to the much more instantly recognizable art of specific bird species in modern artworks. This tied into one of the conference’s most prominent themes: the tension inherent in visual media between artist and audience, especially when the worldview of the artists who worked on older sources was tied up in cultural influences highly different to those of a modern academic observer.

This tension was further examined through the lens of textual media, specifically the very early versions of the Oxford English Dictionary, by Dr. Patricia Stewart. Dr. Stewart is a senior editor at the OED, and as such is uniquely qualified to discuss such ideas within the framework of the then-New English Dictionary. Her lecture drew attention to how the Victorian mode of thinking was applied to that which had come before, namely with no small amount of condescension and disdain; however, medieval quotations were used as sources by the NED, with the Rochester Bestiary providing part of the entry for the lion, and separate entries for the biological and heraldic antelope. Something else she was keen to point out was that in later editions of the OED, scholarship became more understanding of the importance of cultural analyses of the history of words.

The conference’s program of academic lectures concluded on Friday afternoon with a presentation from the organiser, Dr. Diane Heath, on depictions of marine animals in the medieval period. Her eloquent presentation connected the First and Second Family Bestiaries to works of Islamic scholarship such as the Kitab al-Hayawan through their nature as beautiful translations of, and scholarly works discussing, the animal portions of the Corpus Aristotelium. She also contrasted the theological focus of the bestiaries and their use as media for contemplative moralistic study with the more zoological and practical focus of the Kitab and Manafi al-Hayawan. This also circled back to the opening of the conference, as the paper used Achille Mbembe’s ideas of water as a necropolitical liminal space in a manner similar to the exploration of the sea in Dr. Overall’s poetry.

However, the conference did not fully conclude until the next morning, wherein attendees were invited out to sit amongst the flowers and grass of a green space on the university campus. From that scenic point, Dr. Pip Gregory, Eli Salter, and Laine Bloxham gave a lively and engaging talk on the academic and physical methodology of building a pair of resting dragons out of recycled materials. Whilst the majority of the dragons’ superstructures were created from several tons of broken hardcore wheelbarrowed onto a chalk outline, they also incorporated used hessian sacks and partially-dried clay as a sculptable skin and bedding for the plants atop the beasts, as well as a colony of moss and — in the larger dragon — small stones bearing the names of young children with special educational needs and disabilities, so they could have a little ownership of their own heritage.

While listening, I had an opportunity to reflect on the conference as a whole, and how it had approached ideas of “materiality of meaning” from a variety of sources. The dragons were designed to convey ideas of sustainability and the threat of climate disaster through metaphor and analogy: their fiery breath was intended to represent climate instability and rising global temperatures; their backs were covered in drought-resistant sedum plants that would capture carbon and survive the changing world. I could not help but feel some sense of kinship towards the medieval apprentice monks who had studied the bestiaries and used the teachings within them to create pictures and carvings and artefacts of all kinds. I was learning through all my senses, both the physical and the allegorical Fourfold variety, about the wondrous creations in the world around me. The history of medieval animals and their meanings was still right there. I could reach out and touch it.

I did. It touched me back.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1143

1143