This week offers useful information on how to find details of the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2020, as well as a report on Dean Irwin’s CHAS lecture.

I think there may be some confusion about the right website to see the details for the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2020 and to book tickets. This is the website you want: https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury but NOT the Becket 2020 website coming under Canterbury Cathedral ‘The Canterbury Journey’. Yes, there is a notice on their website but NO link to the CCCU site. Due to changes in Arts and Culture staffing, sadly the Box Office in Augustine House is rarely staffed; however Monday to Wednesday inclusive there is someone monitoring the artsandculture@canterbury.ac.uk email address and the phone line at 01227 923690. We at the Centre thank you for your patience and look forward to welcoming you to the Weekend from 3rd to 5th April 2020.

This week I thought I would feature Dean Irwin’s lecture to Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society [CHAS] on Canterbury’s Jewish population in the 13th century. Dean started his talk by introducing his audience to the archives at Westminster Abbey, a place that has almost become a second home for him as he has worked his way through its great collection of Anglo-Jewish charters from across England dating from the 13th century. For, as Dean said, its special status as a Royal Peculiar, firstly abbots owing allegiance directly to the Pope rather than to the archbishop of Canterbury, their successors as deans post Henry VIII’s Reformation owing their allegiance direct to the monarch, has meant that it holds a vast collection of original documents that relate not only to the abbey’s own estates. These others include Crown documents that were produced for the money lending activities of different Jewish communities in England, including Canterbury. Indeed, in terms of the number of such documents Canterbury is second only to London, albeit there is a considerable difference between the two.

Having introduced his attentive audience to the archives’ reading room at Westminster, Dean explained how he had come to be studying the Canterbury Jewish charters and by extension, at least to a degree, the city’s Jews in the century before their expulsion. To provide his audience with some context, Dean offered key features of Jewish history in medieval England beginning in 1066 and William I’s agreement that Jews from Rouen could settle in his new kingdom. This meant that by 1087 there was a community in London based at Cheapside but it should not be thought of as an ethnic enclave, rather economic factors were behind their residence in this area of London, a feature that would apply similarly to the Jews living in medieval Canterbury from the reign of Henry II. Yes, they were to be found in a relatively small number of streets, but equally their neighbours were as likely to be non-Jews as Jews because it was a mixed neighbourhood.

As Dean said, matters were extremely difficult and dangerous, especially for some Jewish communities at various times during first Richard I’s reign and then that of his brother John, but then this period was no bed of roses for many other people either and Magna Carta of 1215 does contain 2 clauses relating to Jews, although these were changed in the 1217 reissue. Moreover, there were periods in Henry III’s reign when these Jewish communities experienced fierce hostility, and his son was similarly prepared to exploit the Jews before expelling them altogether in November 1290.

Yet in broad terms the Canterbury Jews seem to have been on good terms with their Christian neighbours, were prepared to offer the monks at Christ Church Priory practical and spiritual help in the monks’ dispute with their archiepiscopal overlords in the Hackington dispute, and the priory’s possession of an internationally important saint may have played a part in the absence of accusations of Jewish ritual murders of innocent Christian children, which can be found at other cathedral cities. Hence the shadow of St Thomas might be said to have worked for Jew and Gentile alike. Nevertheless, as reported in previous blogs [for example: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/yews-jews-aliens-and-canterbury-world-heritage-site-a-busy-week/ ], Dean did again point out the difficult times the Jews experienced, including at Canterbury, at the beginning of the civil war between Henry III and Simon de Montfort, and then again post Evesham; and also that a poll tax imposed in the 1280s was in no way any more popular than later attempts to use this type of blanket taxation.

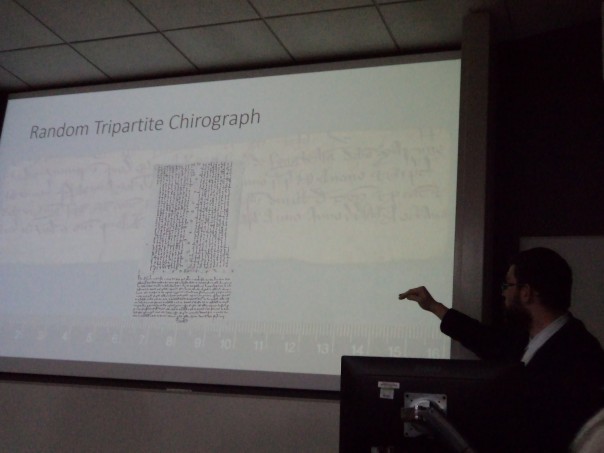

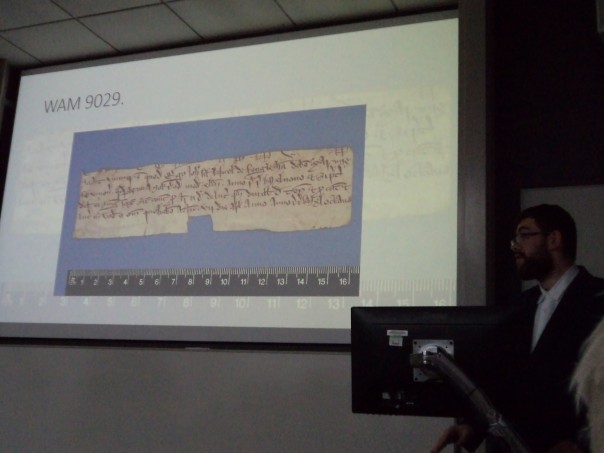

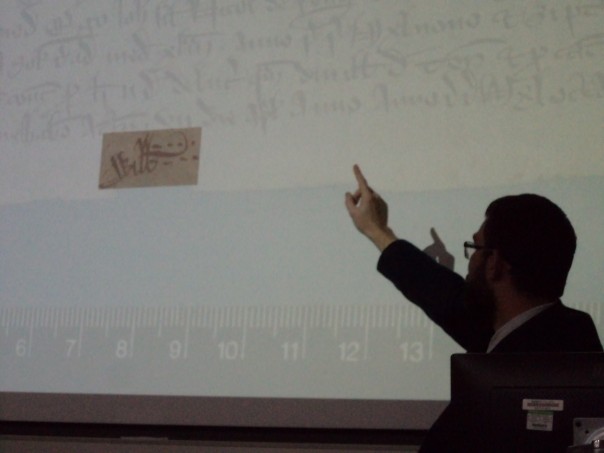

Thus, having provided a fascinating context, Dean took his audience back to the Westminster Abbey archives and to one of the documents. For even though the Jews were not exclusively money lenders, as he was keen to stress, it is these activities that have left the greatest traces in the documentary records. Dean pointed out that last year when he heard Mary Berg’s ‘Urry lecture’ on a particular Canterbury charter, rather than being especially interested in the seal, what had struck him was the handwriting of the scribe. For he recognised the hand as that of Thomas Man who had also been one of the Canterbury clerks involved in the drawing up of documents under the 1233 Statute of the Jewry between 6 April 1264 and 26 August 1273. Such chirographs covering matters of usury were in the form of tripartite indentures where one part was for the lender, one for the borrower and one for the Crown such that if any of the three parts was lost the debt was null and void.

This particular example at the centre of Dean’s talk was the Crown’s part where one John son of Nicholas de Finglesham had borrowed 40s from a Jewess, which Dean said was not unusual. Unlike some other charters of the time this, like all the others of its kind, is dated, and it also records when the debt had to be repaid after which a set rate of interest was to be payable. Consequently, as Dean said, it provided him with answers to his questions: who, where, how much, why, when, all of which he is using in his doctoral study of the relationship between Jewish and Christian communities in 13th-century England.

Such a careful reading of these documents was enlightening, and he was warmly applauded by his audience. Moreover, he then took a considerable number of questions and even after Gill Wyatt, as chairperson, brought the meeting to a close, others came up afterwards to question him further on various aspects of his lecture – a mark of a very successful occasion!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1073

1073