This has been a busy week that has included a fascinating double-bill on Thursday about funerary archaeology and leading a Canterbury Festival walk around St John’s hospital yesterday, a medieval gem which is ‘hidden’ behind its Tudor gateway. I mention the latter because it will also feature in the Medieval Canterbury Weekend in 2018 – see details at www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury

However, what I want to focus on this week is the archaeological talks on Thursday. An expectant audience of staff from Canterbury Christ Church, from Canterbury Archaeological Trust [CAT], Friends of the Trust and students from Christ Church and the University of Kent listened as Dr Jake Weekes from CAT introduced the idea of funerary archaeology as opposed to the study of burials per se. As he was keen to explain, it is valuable to look not just at the bones but to consider matters such as the materials found with them, their placement and anything else that can offer ideas about process within the funerary sequence. Furthermore, this process can also be seen in terms of what those involved believed should happen, their implementation of these accepted actions and the appropriation of these by others who saw them as appropriate. Thus, we also have different audiences to consider in what are complex sequences that can be theorized regarding rites that emphasise separation, as well as incorporation and integration. For, as Jake was seeking to highlight, ideas about liminality, whether we are borrowing ideas from Turner concerning pilgrimage or other scholars’ use of the term, have been used by a wide range of disciplines to try to explore and understand different cultures, albeit Jake sees a degree of shared concepts across time and space – what might be said to be the differentiating features of being human.

Jake outlining his ideas about funerary archaeology.

Lisa Duffy, a Masters student at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, then took up the baton and introduced the audience to her current research and the theoretical ideas that underpin her approach. She, too, values the idea of looking outside archaeology as a way of trying to gain a more nuanced understanding of past cultures, and she has found anthropology to be especially fruitful in her research. Consequently, her supervisor Dr Debra Martin’s idea that ‘the study of ancient and historic remains in a richly configured context that includes all possible reconstructions of the cultural and environmental variables relevant to the interpretations drawn from those remains’ has become Lisa’s watchword for her study of two populations, including one in Roman Canterbury from their skeletal remains.

Lisa’s Roman Canterbury project.

Lisa’s interest is health and she is exploring this in terms of lived experience – the subject’s life course, and performed experience – the funerary sequence, thus linking to Jake’s introductory talk. By examining the bioarchaeological profile of the various skeletons – biological sex, age at death, stature, indicators of stress etc she is linking these to think about stresses in the group, including what buffers there were to nullify these and how members of the population might have also found ways to combat such issues. Moreover, she is seeking to go beyond the individual to see if her findings can be extrapolated to assess the impact on entire populations.

To illustrate how this can be done, Lisa then described her two case studies, the pueblo population of Mesa Verde whose occupation covered about 700 years, finally ending in the late 1270s AD; and those in Roman Canterbury. I’ll come to Canterbury in a minute but first her work on the skeletal remains of 77 individuals from Mesa Verde was extremely interesting. Even though from a personal point of view I would have liked more on their agricultural practices, as well as the communities’ move from the tops to living in the alcoves slightly further down, I fully understand it was outside Lisa’s remit and she was testing ideas about the incidence of violence in this society over time. For the recognised wisdom until recently has been that there were specific phases when warfare took place, an idea that to a larger extent comes from studying western Europe but which may not be applicable in the American Southwest. As Lisa said, her findings concerning cranial depression fractures in the skeletal remains indicate that interpersonal violence took place throughout the 700 years, albeit there were some peaks and she and other scholars now think this reflects violence having been used for different reasons at different times. Consequently, she believes that we need to consider violence as in some ways performative on occasion, that is having particular meanings for the people themselves, some of which may be recoverable through interviewing people from such populations today.

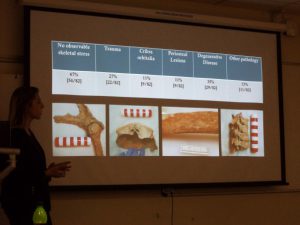

Lisa’s exploration of health issues.

Turning to Roman Canterbury, her second case study concerns the Hallet’s garage site on the west side of Canterbury outside the city walls. For those who know the city, they will recognise it as the site abutting Westgate/St Dunstan’s Street and close to the Canterbury West railway line. The archaeological excavation there was undertaken by CAT in 2009 and 2011 and in total about 200 graves were found, although some were too fragmentary for the type of analysis Lisa wished to undertake. Looking at the evidence, she has found that most of the burials relate to younger people through to middle age rather than the elderly. Taking this a stage further, her examination has sought to classify the different injuries and other trauma these individuals had suffered during life, as well as anything after death, and from this analysis she has come to the following conclusions. Firstly, there were high rates of degenerative disease among a mostly young adult population; in addition, there were three possible cases of sharp force perimortem trauma; next, males and females had equal access to resources, and finally, good overall dental health has implications for the diet of these people, an aspect of the project that she would like to take further using isotope analysis.

Lisa and the results of her analysis from Hallet’s garage.

Bringing this together, Lisa is keen to explore her case studies in terms of the lived and performed experiences of these two populations, because by assessing both she feels archaeologists and others will gain much better ideas about cultural identity, seeing it as dynamic rather than static. As a final point, she drew her audience’s attention to the work of the forensic anthropological centre in Texas that has as its founding principles ‘integrated, engaged, ethical’ and is at present engaged in finding the bodies of illegal migrants who have not been buried in their own grave, using DNA and other techniques to try to identify these people and then posting the results on the ‘missing persons’ register. This allows relatives back in Mexico to search to see if they can find relatives and then the person’s remains can be repatriated for burial in line with the family’s wishes – an excellent idea and a long way ideologically from wall building.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1206

1206