Before I report on the events involving the CKHH this week, that is the Becket Lecture and the Becket and Benedict workshop in the chapter house and cathedral, I thought I would bring a few notices to your attention.

Firstly, although unfortunately I wasn’t able to attend, it was the monthly Lossenham wills group meeting that involves several from the Kent History Postgraduates here. As reported in the minutes by Dr Rebecca Warren, it had been a very successful meeting, and one very interesting point of discussion was the incidence, or more accurately the very few references to musical instruments in Tudor wills and inventories. Indeed, there are a decent number of late medieval references to organs in terms of churches, such as bequests towards the buying or refurbishing of such instruments, but not musical instruments in a domestic setting. Of course, being valuable and valued items, presumably they were more likely to be given as pre-mortem gifts, but still intriguing.

Looking forward, next week includes the monthly Kent History Postgraduates meeting where Jason Mazzocchi will be giving a presentation on early modern Faversham. He has decided to use the questions he had after his presentation at the recent (10 May) study day on ‘Kent and Europe, 1450–1640: Merchants, Mariners, Shipping and Defence’ as a springboard to investigate matters of social status, relationships and networks, as well as identity. If you want to refresh your memory about his earlier presentation, at the Community Cinema in Dover Museum, please see: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/history-postgraduates-in-dover-celebrating-success/

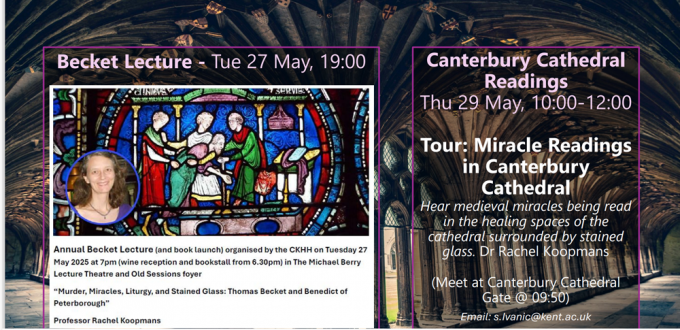

Now to this week and it is excellent to be able to report that we have had two brilliant events, the Becket Lecture on Tuesday and today (Thursday) the Becket and Benedict workshop in the chapter house, then the undercroft and finally the Trinity Chapel. All of this was orchestrated by Associate Professor Rachel Koopmans (York University, Toronto) who is researching the Becket Miracle Windows, currently nIV, with the head of the Canterbury glaziers, Leonie Seliger, and who has just published a translation of ‘Benedict of Peterborough’s Passion and Miracles of St Thomas Becket’.

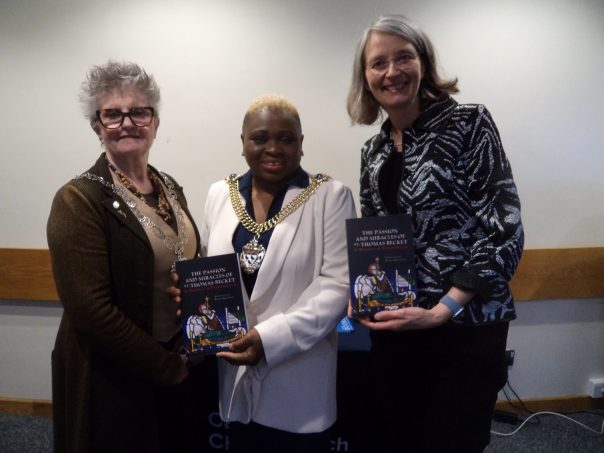

To begin with the Becket Lecture, over a hundred people, including the Lord Mayor, Cllr. Mrs. Keji Moses, and the Lady Mayoress, Mrs. Carol Reed enjoyed the wine reception, sponsored by CCCU’s Unit 28 REF, before moving into the Michael Berry Lecture Theatre in Old Sessions House. Many had also enjoyed looking at Rachel’s new book which Craig Dadds, the manager of CCCU’s Bookshop, had on display there and indeed all the copies he had with him had been purchased by those attending before we went into the lecture theatre. A considerable proportion of these copies had been signed by Rachel, and she also signed copies of other books she has published previously.

These Becket Lectures had been initiated by Professor Louise Wilkinson when she first came to CCCU and when she left Canterbury for Lincoln, it was great to be able to continue the tradition of these annual celebrations where university, city and cathedral may be seen as coming together to celebrate an aspect of Canterbury’s medieval past, albeit I will now be passing the organising baton to someone else because I won’t be at the this university from August. Indeed, as Rachel said in her introductory remarks, this is the third Becket Lecture that she has given and, in this instance, marks the culmination of 14 years of work on her translation of Benedict’s extremely important narrative for a wide range of reasons. Although in some ways the most obvious, it remains true that St Thomas of Canterbury was far and away the most important British saint with the corollary that Benedict’s collect is the most important collection of miracles compiled in Britain. It also marked the start of a boom in the collection of miracle narratives far more widely in western Christendom and for Canterbury itself, it would shortly become the blueprint for the various teams of glaziers who created the great windows showing miracles linked in some way to Becket and his tomb shrine in the eastern end of Anselm’s great crypt.

Yet until now there has never been a full translation of Benedict’s Passion and Miracles, and while a few of the miracles can be found in English in various books on Becket, if anyone wanted to gain a comprehensive idea about the range of these recorded miracles by Benedict in the first years following Becket’s murder, they were confronted by J. C. Robertson’s monumental late 19th-century work of numerous Latin texts in what he called Materials for the History of Thomas Becket. Recent scholars have given readers some ways into Becket’s life, death and miracles in several important books, such as those by Anne Duggan, Michael Staunton, and William Urry, but the field remains open and as well as the gap that Rachel has now filled, there are still no modern editions of several key texts, including various contemporary lives of Becket by William FitzStephen and Edward Grim to name but two, while William of Canterbury’s Life and Miracles also await a modern translation.

I won’t go into the reasons Rachel thinks have contributed to the lack of such editions but instead give a quick summary of Benedict’s life to show where he fits into the Becket story. He was possibly born in the 1130s of Anglo-Norman parents, perhaps a local Kent boy who entered Christ Church Priory as a young novice, being there when Becket was murdered and still there when the first miracles were happening. At a very early stage, he seems to have wanted to record the miracles, perhaps from late spring 1171, but the Passion came later, Rachel thinks he composed that in 1172, with the Prologue and parts of his Book 1 later still. All this industry meant that the text began to circulate in mid 1173 and he decided to add 9 further chapters before stopping. Becket had been canonised in February that same year and Benedict composed the liturgical office for Canterbury’s new saintly archbishop which was first celebrated on 29 December 1173.

The fire of 1174 gave more urgency to matters relating to St Thomas’ cult and having been elected prior at Canterbury in mid 1175, Benedict was heavily involved in the early reconstruction until his departure for Peterborough in 1177 when he was elected abbot. He didn’t depart empty handed, taking with him several Becket relics including the paving stones on which Becket had died and a large number of manuscripts. Moreover, as Rachel amusingly demonstrated, he returned to Canterbury again and again and therefore would have seen much of the early stained glass, even if not the Translation because he died in 1193.

During his time at Peterborough, he showed himself to be an excellent administrator and someone who could deal with the highest in the land, an important skill then as now. His decision to leave the Life of Becket to others may be illustrative of this skill because in concentrating on his first-hand account of the murder, he was not drawn into the controversies surrounding relations over time between king and archbishop. Unfortunately, there is no surviving complete copy of Benedict’s Passion narrative, in particular the prologue is lost but, as Rachel said, we have enough from the remainder in the late medieval compilation of the lives of Becket known as the Quadrilogus II. Furthermore, what survives by way of extracts is enough to read well and provide valuable details, as well as reiterating the linkage seen in other narratives of Becket to Christ’s Passion. Additionally, Benedict offers significant information about the monks’ reactions and actions during the episode, as well as what Becket’s head, in particular, looked like as he lay dead on the paving stones. This Rachel illustrated which shows just how graphic the description was and thus how this may have affected the monks when it occurred and during the reminder provided in Benedict’s narrative.

Moving on to the Miracles, Rachel explored the problem of how do you count them, which is far more difficult than first appears. Consequently, as she illustrated commentators have to a degree side-stepped the issue and instead count chapters instead. Benedict’s work is divided into 282 chapters which means that there are over 275 miracles because not all the chapter have them, but it still provides a helpful ball-park figure. So compared to others’ work this is a truly remarkable achievement, not least because Benedict was selective, saw the necessity of testing the evidence in 12th-century terms and wanted to know if the miraculous recoveries were sustained. He was equally keen to demonstrate the range of miracles Becket was seen to accomplish, as well as the role in such narratives of the Becket Water and the tomb shrine.

To finish, Rachel took us through a couple of the miracle narratives to illustrate the points she had been making. The audience was extremely enthusiastic in their applause for such a tour de force and there were a large number of excited questioners who posed a wide range of questions, illustrative of what a great presentation we had just witnessed. Consequently, at the conclusion, Rachel received another great round of applause, and all agreed that they had indeed witnessed the best of outreach and knowledge exchange one could hope for, a testimony to the role and importance of the Centre over the last decade. Indeed, Rachel endorsed this view and in her closing remarks she indicated how much he had enjoyed and appreciated this collaborative relationship as well as seeing how people – from Canterbury to North America had come to enjoy and benefit from being audience members at the numerous workshops, lectures and history weekends. This drew a standing ovation, so thanks Rachel for voicing such sentiments in public, which others have similarly expressed privately over the last few weeks.

Today saw another example of collaboration and willingness to share knowledge when a group of MEMS post-doctoral, doctoral and MA students from the University of Kent and CCCU joined staff from both institutions and a doctoral student from Oxford in the chapter house. There we met Rachel and Leonie Seliger to explore the relationship between Benedict’s Miracles and the stained glass on the northern side of the Trinity Chapel. As befitted a workshop scenario, Rachel provided some background information and then gave everyone who was happy to be involved a short miracle narrative. For, as she said, we know from contemporary sources that in the early years while Benedict was busy composing, these narratives were read to the monks and their honoured guests (those literate in Latin), not ‘ordinary’ pilgrims, in this space, albeit the chapter house has undergone major rebuilding work, especially in the late 14th century.

To facilitate as closely as possible a recreation of such readings, Rachel first asked people to work with a partner to read their narratives and to think about their initial responses before coming out one at a time to read ‘their’ narrative to everyone and comment on their response. Rachel had selected a range of stories, from those linked to the tomb shrine itself to one on the blood and water relic and another on the shift from wooden pyxes to metal ampullas. Then we had a variety of illnesses, some pretty gruesome to show Becket’s ‘versatility’ when it came to curing those who sought his aid, and finally a range of narratives, including the problems of barking dogs and a lost cheese.

It was fascinating to listen to the different responses, and having heard them like this, it was clear how Benedict had honed his narratives, and how he had drawn on the stories told by pilgrims who came to the tomb shrine in the crypt, which was where we headed next. There Rachel described how having come through Anselm’s crypt the chapel at the east end of this would have been much smaller and darker than it is today – possibly not that dissimilar to Bayeux cathedral crypt today. Also, there was the watching gallery to ensure there was no desecration and generally to oversee the pilgrims. Having thought about this space and what it may have meant to the pilgrims, we considered where it is possible that the blood and water was dispensed, and one of the side chapels with its own altar seems a good possibility.

Finally, we made our way to the Trinity Chapel to consider the Becket Miracle Windows on the north side, those closest to Benedict’s dates, which illustrate a range of miracles in different numbers of scenes but demonstrating just how challenging it can be to translate a long and complex narrative into a few workable scenes. Moreover, as Rachel explained, just as she was describing a specific miracle to us, so the monks would have done to the pilgrims, which explains why the glass in the window is so low down to allow pilgrims to really see what is going on.

This was a fascinating event, and Rachel was warmly thanked for providing such an imaginative and thought-provoking workshop. Additionally, it had offered an excellent chance for the postgraduates from all three different universities to get together and think about audience, authorship, transmission of knowledge, identity, and the relationship between spiritual and bodily health. Many thanks Rachel, it has been a fantastic week!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2763

2763