Before I give a brief report on Professor Paul Bennett’s fascinating ‘Part Two’ of his inaugural professorial lecture, I thought I would mention a few events the Centre is running in early 2018 and also the ‘Picture this …’ Advent entry for today: www.canterbury-cathedral.org/heritage/archives/picture-this/summer-blooms-a-wonderful-transformation/ and what could be better than flowers in summer?

Firstly, it will be the Annual Becket Lecture at Canterbury Christ Church on Tuesday 23 January and the lecture in 2018 will be given by Dr Marie-Pierre Gelin. Details will be available soon, but I thought I would say that her primary research interest is the ecclesiastical and monastic history of England in the period 1000–1250, with particular focus on visual culture. Furthermore, she is currently working on the role of relic collections and inventories of books and ornaments in the construction of memory and identity in English monasteries, and I’m sure her lecture will provide fascinating insights regarding this or an allied topic.

Black Prince [image copyright Dean & Chapter Canterbury Cathedral].

The Centre’s Medieval Canterbury Weekend on 6–8 April, will feature a wide range of topics from medieval manuscripts: Professor Michelle Brown’s discussion of the role played by Canterbury and the South East in shaping the artistic and cultural development of Britain from the Celtic Iron Age to the Norman Conquest; to ‘dastardly’ kings: Dr Marc Morris’ examination of John’s career and character, setting the king’s actions against the standards of his own age; to medieval drama, Dr Clare Wright’s investigation of tournaments, saints’ plays and interludes – plays performed between courses at banquets, between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. Details of all these lectures and far more at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury

Between the Becket Lecture and the Medieval Weekend, the Centre will be working, under Professor Louise Wilkinson’s leadership, with several outside organisations such as Faversham Town Council and the King’s School, Canterbury, toward an exhibition on ‘Medieval Faversham’ with the former and a series of sixth-form workshops with the latter. This will involve working with Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, a relationship that is also fostered through the History Weekends and other related activities. Within the university, too, the Centre is building relationships with the geographers and plant scientists, our first joint venture being the Garden History Study Day back in October, and we are intending to hold more of these events. Furthermore, within the Humanities, there is now a growing group of postgraduates who meet monthly to discuss their Kent history research, and it is very interesting to see how ideas and topics can transcend periods of history – modernists, early modernists and medievalists finding a great deal of common ground.

Perhaps the Centre’s most wide-ranging relationship is with Canterbury Archaeological Trust, because not only is Paul Bennett, the Trust’s Director, a Visiting Professor in the Centre, but Professor Jackie Eales, through Christ Church, has supported Dr Jake Weekes’ work at the Trust in terms of the digital mapping project covering ‘Twenty Centuries’ of the city’s history. Jackie and Jake are now talking to the Historic Towns Trust and it is hoped that at some future date Canterbury will join the likes of London and Oxford for which there are now excellent historic atlases. Other projects involving collaboration include the HLF-funded ‘Finding Eanswythe’, as well as the joint lectures organised by the Centre and the Friends of the Trust, many of which feature in the blog.

Paul Bennett and Lawrence Lyle

Turning now to Paul’s lecture last night, an eager audience settled in to the Michael Berry Lecture Theatre in Old Sessions House to hear the second instalment. Paul began by reiterating his life-long thanks to his mentor at the University of Manchester, Professor G.D.B. Jones, who had helped him throughout his time there and had given him the opportunity to work as an archaeologist in Libya early in his career. Paul then paid tribute to Lawrence and Marjorie Lyle, dedicating the lecture to them for all their amazing work on behalf of the Trust since its foundation. Indeed, Lawrence’s decades of work as company secretary predate Paul’s own arrival in Canterbury, and Marjorie’s enthusiasm and drive concerning the Trust’s shop and other projects have over the years saved the Trust during some tricky financial times.

Although I shall focus on Kent, and Canterbury in particular, because of the nature of the Centre, Paul’s love of Libya, its archaeology, history and people shone through on Tuesday night, as it always does, for both are close to his heart. Moreover, having worked on countless archaeological excavations in Libya, Paul has an intimate knowledge of just how important many of these city and (desert) sites are internationally for what they can tell us about prehistory, in addition to the times of the classical civilizations right the way through to the Arabs and Byzantines. Consequently not only has he been involved as a field archaeologist, being part of teams working on the stratigraphical sequence that through the abundance of the coin finds can now be used to date Greek fine-ware pottery, but his expertise has been called upon to produce policies on heritage, conservation and sustainability. He has been heavily involved in the latter for about a decade, seeking to show first Colonel Gadafi and more recently successive governments why and how this vast treasure trove of sites should be cared for, a vital sector of the country’s economy through tourism, for example. At the moment, bearing in mind the state of Libya, almost all of this has fallen on deaf ears and the Libyan archaeologists Paul and CAT have trained, and in whom Paul is very proud, will largely now have to wait to see if and when conditions improve sufficiently to continue their good work, supported by archaeological teams from Britain and other countries.

Paul and the Poor Priests’ Hospital

In Kent and Canterbury, even though the causes are not the same, the effects in terms of the county and the city’s heritage have at times been sufficiently damaging that a considerable part of the archaeological record has not been investigated thoroughly, but instead has gone in the ever-growing wave of redevelopment. Furthermore, unlike most historic towns and cities, Canterbury no longer has a museum or even an exhibition dedicated to showing the city’s past following the closure of the Canterbury Heritage Museum. As Paul said, the Poor Priests’ Hospital, that until recently housed this museum, is a gem of a medieval stone building in its own right and he was privileged, as he sees it, to have worked on it. Thus, there is probably no one who knows it better from its early 12th-century beginning, as first two houses and then one held by Lambert Frese from Canterbury Cathedral Priory, to its first incarnation as a medieval hospital for poor priests. Nor did matters stop there because in the later 14th century the orientation of the open hall was changed by 180 degrees – the high end became the low end and vice versa. Its later medieval life is equally interesting and then on into the later 16th century where it became the city’s bridewell, later charity schools and finally a whole range of other incarnations before the museum.

Paul and the Canterbury Christ Church site

Throughout his lecture, Paul paid tribute to many of the Trust staff, both former and current members, who have given of their expertise and worked tirelessly, whether as excavators, as building recorders, as post-excavation specialists, as writers and as educators, the latter being an important and valuable part of the Trust’s portfolio of activities. Among those Paul named were Alison and Martin Hicks for their work on St Gregory’s Priory, and more latterly Alison’s work on The Whitefriars and CCCU’s own site – the outer precincts of St Augustine’s Abbey; and the building recording team (past and present), including John Bowen, Rupert Austin and Peter Seary. They have worked on most of the buildings at one time or another within the cathedral precincts, as well as many timber-framed structures such as Cogan House, Canterbury’s great inns – the Chequer, the Bull, the Sun and the Crown, the corner properties on The Parade, and Eastbridge Hospital with its wonderful lantern roof turret.

Paul, Frank Panton and the Dover Boat

Of course there is far more in Canterbury and I cannot give justice to Paul’s encyclopedic knowledge as we went at a breathless pace from site to site, but it wouldn’t be a Paul Bennett lecture if the Dover Bronze Age boat was not mentioned. For, as Paul said, boats have been another of his major passions, alongside dogs and cricket. Thus he sees the small-scale replica of the ‘Dover boat’ as part of his flotilla, and he was an integral part (indeed the skipper) of the group that took part in The Great River Race not just once but twice – 29 miles on the Thames and under 27 bridges. Nor is it merely the replica that is important because the remains of the boat found by Keith Partfitt and his team in Dover has been the main attraction in the award-winning Dover Boat gallery at the town’s museum under the excellent curatorial governance of Jon Iveson, another long-term friend of the Trust, especially the Dover outpost. Also heavily involved in this ongoing project, including much scientific analysis, is Peter Clark of the Trust, and, until his death, Dr Frank Panton, whose amazing career spanned military science through to archaeology. As well as serving as Chairman of the Trust for many years, including the period of the discovery of the Dover Boat and the subsequent work to preserve and study her, Frank was for many years a major figure in Kent Archaeological Society.

As I hope you can tell, the themes running throughout Paul’s talk were collaboration, co-operation and team work, although what he didn’t stress was that much of this is down to Paul having been at the helm (to borrow another of his nautical metaphors), without that it wouldn’t have happened. Yet it was clear that Paul was at the centre of this great wheel of endeavour, an idea which both Lawrence and Marjorie took up when they responded to Paul’s talk at its conclusion. Thus for 75 minutes Paul took his audience through a breath-taking range of sites in this country and abroad, showing the problems as well as the triumphs, and a life lived at break-neck speed. Yet, perhaps everyone’s lasting impression was first and foremost of a man whose enthusiasm for the subject is as great now as it was when he started digging as a teenager.

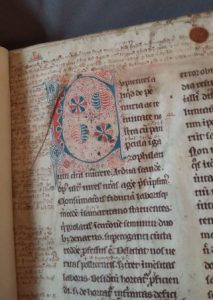

Lombard’s Sentences – Rochester Cathedral Library [photo Diane Heath]

Finally, someone else whose enthusiasm is boundless is Diane Heath, who with Dr Sarah James and Sarah Field, fellow medievalists, were on Wednesday leading a series of workshops at Rochester Cathedral and its library on ‘the Image on the Margin’ (adapting Michael Camille), focusing primarily on manuscript marginalia. The day was organised for the University of Kent’s Medieval and Early Modern Studies postgraduate students and Friends of MEMS, and demonstrates the value of collaboration between the two universities based in Canterbury.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1197

1197