Although not quite changing decisively hour by hour, things do seem to be doing that on a daily basis as national leaders scramble to keep abreast of this pandemic in various ways. This is such a tough time for so, so many across the world, including a whole host of groups and individuals in this country, and it is vitally important that everyone supports those working in health and care services wherever they are who are doing a brilliant job.

Like the rest of the tertiary educational sector, CCCU has physically closed, with those who can working from home, and home is now spread across the country as staff members headed off to be with family members at this challenging and very uncertain time. Consequently, online teaching has become the name of the game. This transition, from being a face-to-face educational establishment where lectures, seminars and labs were standard practice on campus to interacting through video and audio links with other forms of learning and communication, has been a steep learning curve for many. Indeed, I have been finding out about systems I had never even heard of let alone used in the past, and I cannot say my little corner of all of this has yet got to grips with everything. So even though there have been several setbacks: we didn’t manage to connect with Janet Clayton and Maureen Mcleod this morning, and Jacie Cole couldn’t get back in time to join in, the Kent History Postgraduate group is back in business! For there were four of us connected by video link this morning: Dean Irwin, Peter Joyce, Jane Richardson and me, and this was especially brilliant because Jane, having, we think, caught the virus and thus self-isolating, seems to be on the road to recovery.

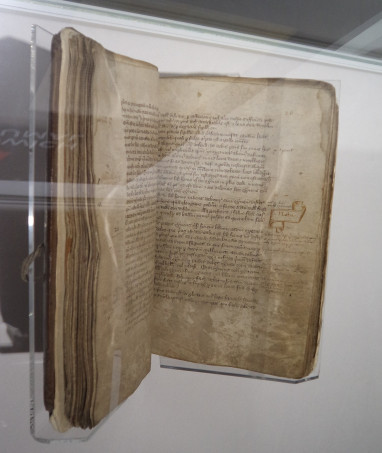

We had expected to encounter technical difficulties, and as you can see we did, which meant we decided to use our first ‘meeting’ to catch-up, find out how each of us was coping, from Dean in the Manchester area to Peter and Jane in Kent. As you can imagine, as well as issues about getting food supplies and medicines etc, the conversation turned to matters relating to the sudden shutting of archives across the country, which is critical for all the postgraduates in different ways. For example, Dean is due to submit his doctorate this September and he was just about to embark on a concentrated study of records concerning the medieval Jews of Lincoln held at The National Archives. He is now stuck, and even though, yes, he can do some editing of his other chapters etc, the likelihood of having no archival access for potentially several months is exceedingly stressful at such a critical time. For he needs to finish in September – his CCCU scholarship runs out then, extensions are potentially costly, and post-doctoral applications that have their own timetable. He is waiting for official clarity on all of this, which he hopes will come ASAP. As do, of course, a whole host of other final year MA Research and PhD students, thereby giving them, hopefully, piece of mind and allowing them to get on and complete whenever without suffering any financial penalties due to circumstances way beyond their control.

Although much earlier in their doctoral ‘lives’, Jane (and Maureen) can be seen as typifying postgraduates confronting related issues because they, too, need access to archives, as well as, like Dean, the university library (although the excellent work of the library staff to make as much available as possible is greatly appreciated), printing facilities etc. They had similarly planned visits to TNA, as well as to Lambeth Palace Library (due to close at the end of April 2020 for the rest of the year as it’s moving, but, now, of course, already shut) and probably most significantly at the moment, the Kent History and Library Centre at Maidstone. Yes, there are a few printed sources, and currently some material can be accessed at a price digitally from TNA, but for documentary researchers this is a serious blow. Thus they, like other postgraduates, will be concentrating on secondary materials for the time being, but longer term, as at universities across the country, considerations about extending registration with no additional fees will be important, indeed vital for many.

And now for something completely different, I thought having had a Sandwich topic last week I would stay in the same town and do a piece about a non-event – when what should have happened didn’t and the repercussions as a result. The event is question was a procession that should have taken place from St Peter’s church in the middle of the town to St Bartholomew’s hospital chapel on the outskirts on 24th August 1532. It seems that as usual the mayor and jurats with the commonalty had met at the church with their tapers. Presumably the town musicians were all in place too, as well as the parish clergy and the chantry priests. But that was when it all started to go wrong. The curate Sir John Yonge refused to take part in the procession if he wasn’t allowed to officiate at the high mass at the hospital chapel, and it seems the chantry priests backed his stance. The mayor and jurats weren’t prepared to accept this and commanded that the curate, chantry priests and church wardens should be arrested, and it seems likely the day ended in total confusion.

Ok, you may say, an interesting snippet from the archives, but does it matter? I think it does because it highlights religious tensions and how these were being played out not only at Henry VIII’s court, but in parishes and towns. Furthermore, religion was part of a complex mix of socio-economic and political issues that all played their part in Civic–Church relations in 1532 and beyond.

Leaving aside the churchwardens, Sir John, who seems to have been a relatively recent incumbent, apparently left Sandwich within two years of the incident, because his successor was listed among the beneficiaries of a local will dated 1534. The chantry priests involved were the three priests at Thomas Elys’ chantry in St Peter’s church, a foundation established in 1392. Sir John Stephynson was possibly the most senior. He had served at the chantry for twenty years in 1532, and he seems to have been an active and well-respected member of the local community. His death in December 1533 (he was found drowned at the bottom of his own well) may not be linked to the events of the previous year, but he had suffered official censure in the intervening period. The other long-serving chantry priest, Sir William Ussher, was replaced in 1534, while the third, Sir Thomas Philipp, had been removed a year earlier (June 1533) and sent to the Poor Priests’ hospital in Canterbury. The mayor and jurats justified Philipp’s removal and replacement by Sir Edmund Grene, a chaplain “of good conversation,” by saying that Philipp’s fellow chantry priests had acted wrongfully in allowing him to keep the position because he was a beneficed priest. Before taking this action the mayor and jurats had had the chantry foundation charter read to them, thereby publicly confirming their legitimacy to act as patrons, first because the other chaplains had been at fault and second because the civic authorities saw the chantry chaplains as ‘theirs’ from ‘ancient times’, the process made legally binding through the use of the town’s seal. As a consequence, the leading town officers had publicly re-established their control over the chantry and the procession, and in the process had penalised the clergy at St Peter’s by replacing them with more malleable priests.

William Stokes, the rector in 1532, who might have been expected to officiate at the high mass in St Bartholomew’s chapel, is not mentioned at all in these proceedings. Nor is he recorded in any capacity in any Sandwich wills, a situation apparently shared by his predecessor and successor. As far as these latter men are concerned this may be because they were nominated by the abbot of St Augustine’s (clerical appointments were shared by the abbot and the mayor, taking it in turns), and it is possible they had little involvement in the parish, their pastoral and other duties being undertaken by the curate. Although the year of Stokes’ appointment as rector is unknown, the evidence from the town books points to 1528, that is, five years after Sir Henry Guldeford, of the powerful west Kent family, first sought the position for his chaplain, the mayor and jurats agreeing to his request in 1523 for the next nomination on the grounds that Sir Henry had previously aided the town and the Cinque Ports more generally.

This was not the only favour they granted the Guldefords. Two years later Sir Edward Guldeford’s man was given the office of sergeant of the mace. Sir Edward, as warden of the Cinque Ports, was an even more powerful figure than his half-brother, and both men were important courtiers and favourites of the king. Nevertheless, there seems to have been a degree of unease on this second occasion, the mayor and jurats deciding that their actions should not set a precedent and in future no other town offices were to be granted as favours, yet when Sir Henry and Sir Edward presented their candidate in 1528 he appears to have been approved without any difficulty. Whether this relates at all to a desire on the part of the civic authorities to endorse the Guldeford’s humanist ideas or to appoint a cleric with reformist ideas is unclear, but Stokes’ apparent inactivity in the life of the parish might imply Sir John Yonge’s expectations in August 1532 were wholly justified.

Consequently, did the churchwardens want to thwart him by giving the honour at St Bartholomew’s chapel to one of the Elys chantry chaplains instead? The actions of the mayor and jurats would appear to point to this conclusion. In terms of longevity there was relatively little to choose between Stephynson and Ussher: the latter was an Oxford university graduate, but it is feasible that Philipp was too. Furthermore, the latter’s recent appointment to the chantry in 1529–1530 may suggest that he is the most likely candidate. Whether the upstaging of Yonge by the churchwardens related to the curate’s religious views is very difficult to know. Neither Philipp nor Yonge had had much time to be involved in the wills of those from St Peter’s parish, but it is interesting that one of the very few wills Yonge had witnessed, and in the leading role of first witness, was that of Alexander Alday, gentleman. Alday was a relatively young, prosperous jurat and member of a substantial landholding family in east Kent, who made his will in the spring of 1532, possibly during his last illness because he died in May, three months before the date of the procession. Unusually, his testament barely mentions his funeral or commemoration. He made no pious bequests beyond sums of money to the high altar and for church repairs (very standard bequests), the remainder of his will being devoted to gifts to his pregnant wife, two daughters, and his overseer. His extensive property was in the hands of his feoffees, including his fellow jurat Richard Butler. Even though such evidence is notoriously difficult to use to assess personal religious convictions, it is conceivable that Alday’s instructions indicate that he, and perhaps also Butler and Yonge, were interested in Humanism or possibly even more radical religious ideas. Alday’s death, therefore, may have robbed Yonge of much needed support and protection in August 1532 and may imply that the churchwardens were not sympathetic to his views.

The mayor and jurats were seemingly equally unsympathetic. Rather they viewed the incident as a serious disruption of their ancient quasi-religious civic ritual. This breach in the town’s customary order seen as damaging their authority, all part of Sandwich’s civic identity that drew on ancient rights and privileges, and responsibilities which included oversight of the town’s charitable institutions. Of these St Bartholomew’s Hospital was of greatest consequence, not least because the saintly saviour of the town was commemorated there, and the refusal of the St Peter’s clergy to fulfil their duty not only meant the mayor and jurats could not fulfil theirs either but meant the whole town risked divine as well as mortal censure. Consequently, as upholders of the king’s royal authority and justice in Sandwich, the mayor and jurats were confronted by a situation that required them to act quickly to regain authority. Their need may have been especially pressing for two reasons. First, the king and a large entourage were due to pass through east Kent in September en route to a meeting with the French king in Calais, and even though this was not due to take place immediately, preparations had already begun. Second, the civic authorities, and particularly certain jurats, were still involved in the dispute over the role of the king’s bailiff in the town.

In 1532 the senior jurats who were particularly implicated in the at times violent clashes with the king’s bailiff, Sir Edward Ringley, were Henry Boll, Roger Manwood, and Vincent Engeham, and it may have been these men (and others), with the mayor John Boys, who took the lead in the imprisoning of the various parties from St Peter’s. Notwithstanding that for all four self-interest may have played a part in some of their dealings, Manwood and Engeham also seem to have seen themselves as staunch supporters of the town’s interests in the preceding decades, and Boys, as a local gentleman who purchased the freedom in 1528 and became a jurat the same year, may similarly have been concerned about civic authority and identity. Moreover, it was the priests as individuals rather than the clergy as a whole who were seen as having broken the divinely sanctioned, ancient agreement between civic and clergy, and it was, therefore, the town officers’ duty to punish them. Furthermore, the testaments of all four men contain pious bequests that indicate strongly held orthodox Catholic beliefs. For example, Boll and Manwood left bequests to numerous lights in their respective parish churches, and Engeham wanted an orthodox Catholic funeral, which is especially revealing because he made his will in May 1547. Yet probably equally informative is Manwood’s instruction concerning his tomb. He wanted to be buried next to his late wife in St Laurence’s chancel in St Mary’s church, the grave covered by a stone on which there was to be a brass showing himself, his two wives and six children; at the corners were to be four shields, two having the arms of the Cinque Ports, one showing the cross of St George, and the fourth having “a token of deth on it.” Age may have been a critical factor: Boll, Boys (in 1533), and Manwood (in 1534) were elderly men when they died, and even though they, like others in Sandwich, would have been well aware of the parliamentary and royal decisions emanating from Westminster, there is nothing to indicate that they would have taken a lead from them beyond their traditional stance on lay–clerical matters.

So did this change in 1533 and 1534 when first Philipp and then Ussher were replaced by Grene and Lawney respectively? In 1532/3 the mayor was John Pyham, whose will, made eight years after his mayoralty, does not reveal deep religious convictions of any form, and perhaps more indicative of his stance is an order in the town book made during his mayoralty to revive certain annual payments due to the town that were recalled as being part of its ancient customs. As mayor he may, therefore, have been perfectly at ease with the idea of upholding the civic dignity of Sandwich against those seen as malefactors, and may even have initiated later that year the similar recalling of the Elys chantry charter and the subsequent injunctions against the serving chantry priests. Consequently, the decision to replace Philipp and the process involved appear to have been in keeping with the ideas and concerns expressed the previous year.

What happened in 1534 is more problematic because it is not clear exactly what process was used to remove Ussher, or what happened with respect to Lawney and Newman. As a result the role of the mayor and jurats in the events of 1534 is difficult to assess, especially the degree to which the deaths of several senior jurats and Alexander Alday had affected the town’s governing body, but in broad terms the magistracy remained conservative in outlook. Yet the appointments of Grene in 1533 and of Lawney the following year, may indicate an important (if unintentional) ideological shift, that influenced the course of the history of the Reformation at Sandwich. The town book does not record who nominated the Oxford graduate and reformist cleric Sir Edmund Grene to the mayor and jurats, but the most likely member of the magistracy is Richard Butler (see above). Yet it is also possible that the proposal was endorsed by John Master because Master was mayor in 1528 when the Guldefords received the right to nominate the new rector at St Peter’s. As a wealthy merchant Master had overseas contacts that may have influenced his religious affiliations, and his involvement in the provisioning of Calais may also have contributed to his support of the regime’s standpoint. Familial rather than overseas connections may have been the main contributory factor regarding Richard Butler’s reformist views, and he seems to have been an early convert. His later activities in the reformist cause included aiding Sir John Crofte at St Mary’s church to pull down the images there, and among the witnesses of his will made in 1545 was the locally very active reformer William Norris.

However, when Grene arrived to take up his office, such destruction was almost ten years in the future and the mayor and jurats may have believed they had just appointed a cleric “of good conversation.” How outspoken he was initially is unknown, and similarly unrecorded are the activities in Sandwich of Thomas Lawney, another Oxford man who arrived in 1534 at Grene’s invitation, but Lawney’s almost immediate replacement by John Newman is suggestive. It may reflect a local desire to remove at least one reformist priest from the town, though equally it may indicate a move by the reformists to provide greater preaching opportunities for him in east Kent. Nonetheless, for the probably tiny number of townspeople interested in reform, Grene’s arrival was important, offering support for the only other known clerical reformist in Sandwich, Sir John Crofte the curate at St Mary’s.

Thus, the nomination of Sir Edmund Grene to be a chaplain at Elys’ chantry may mark a shift in civic–clerical relations, though how far this was ideologically motivated rather than personal remains unclear. Yet if it was a criticism of the clergy it is important because not only did it mean that there were at least two reformist priests in the town, perhaps acting as a catalyst for the Reformation there, but also the appointment of such a cleric (whether unwittingly or not) had been made for the benefit of the town by those representing the town, not by an outsider. In contrast, and even though it occurred only in the previous year, the violent censure of the clergy and others by the mayor and jurats after 24 August 1532 seems to reflect disapproval of specific individuals, not of the clergy per se. This difference is important with respect to the ways the people of Sandwich experienced the Reformation, but also because it opens up ideas about why civic ritual was valued and by whom, how “competing constituencies” were prepared to negotiate their places/roles in it and society more broadly, and what happened when conflict occurred. So I hope I have shown that the events of 1532, although apologies for the length of this piece, can provide valuable and fascinating insights on the complex relationships that individuals and groups engaged in as they sought to negotiate political and religious dynamics during a crucial period in the 16th century.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1337

1337