Good news, firstly Craig Dadds at the CCCU Bookshop tells me that the ‘virtual bookshelf’ for the Tudors and Stuarts Weekend is now up, please see: https://bookshop.canterbury.ac.uk/tudors-and-stuarts-weekend-2025 and secondly, I have heard from both Professor Rachel Koopmans and Victoria Stevens which means that this week I can provide details about the Becket Lecture and the Nightingale Lecture respectively.

Furthermore, and in consultation with Craig, we now have a date for the Becket Lecture because it is envisaged that this will also be a book launch for Rachel Koopman’s new book (see below). Thus, the Becket Lecture will be on Tuesday 27 May at 7pm, wine reception from 6.30pm, in the Michael Berry Lecture Theatre, Old Sessions House and is a free public lecture – all welcome. The lecture is entitled ‘Murder, Miracles, Liturgy, and Stained Glass: Thomas Becket and Benedict of Peterborough’. For as Rachel says: “This lecture will present the argument that the Benedictine monk and later abbot Benedict of Peterborough (d.1193) was the single most pivotal figure in the creation of Thomas Becket’s saintly reputation. Before any other Becket hagiographer put pen to parchment, Benedict began collecting stories about the new saint’s miracles. His collection of some 275 stories became by far the most widely circulated miracle collection composed in England, with manuscript copies making their way to Portugal, Poland, Denmark, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and Iceland as well as many locations in Britain and France. Present in Canterbury on the day of the archbishop’s murder, Benedict wrote one of the earliest and most gripping accounts of his brutal death. It was Benedict who composed the music and text of the liturgical Office utilized throughout Latin Christendom to celebrate Becket’s feast day, a text that draws heavily on his earlier compositions and survives in hundreds of medieval manuscripts.

In addition to all of this, it was Benedict’s writings that served as the principal source texts for the glaziers of Canterbury Cathedral as they created the famous Miracle Windows series. There are very good reasons to think that Benedict was the brain behind the overall glazing programme for the newly rebuilt eastern end of Canterbury Cathedral, with its closely interconnected sequences of Ancestor Windows in the clerestory, Bible Windows in the choir, and Miracle Windows in the Becket chapel. Benedict was the prior of Canterbury at exactly the right time for the planning of these windows, and his fingerprints look to be all over them.

Nevertheless, Benedict of Peterborough is the most important figure in the Becket cult that you’ve probably never heard of. Consequently, this lecture will serve as a launch of The Passion and Miracles of St Thomas Becket by Benedict of Peterborough, published by Boydell Press in May 2025. This is the first English translation of Benedict’s remarkable (and very readable) works.” It is therefore brilliant that Rachel’s translation of this pivotal work will be launched in Canterbury within yards of Benedict’s great cathedral and within the site of St Augustine’s abbey, the city’s other premier Benedictine house and the location of St Augustine’s shrine – seen as Canterbury’s two saintly protectors.

Similarly exciting, Victoria Stevens has sent details of her Michael Nightingale Memorial Lecture, which as reported last week is a joint undertaking between Brook Rural Museum and CKHH. This will be on Tuesday 23 September at 7pm, again with a wine reception from 6.30pm and is an open public lecture. The title of her lecture is ‘Conserving Intangibility: the significance of change in heritage collections’ which is a highly pertinent topic today as museums and other heritage establishments seek to make their exhibits understandable, relevant and approachable for 21st-century audiences, whether they are Victorian or older farm tools or manuscripts and books from the same era. For as Victoria says “This talk will seek to identify where significance in heritage lies and demonstrate the opportunities for this to be explored and maintained through conservation and preservation interventions. Using a series of case studies, based specifically on the speaker’s specialist area of written heritage, this presentation will demonstrate that meaning can lie beyond the overt or apparent object and be held in evidence of human interaction, including what we have previously seen as damage. It will investigate the way that the changes an object has undergone in production, use or subsequent storage can impact the way heritage objects are interpreted and understood, and the added value and holistic view this can provide. Finally, it will seek to highlight some of the analytical techniques that are available to conservators to gain this information without invasive treatment.”

Keeping with the subject of objects from the past and the idea of ‘heritage collections’, I want to take this sideways slightly because the proofs for my article on the ‘Becket mazer’ arrived this week. I mentioned this back in 2020/1 in relation to my online paper at the conference which took place to mark the commemoration of Becket’s 1220 Translation. Due to the problems of the times and changes in terms of publication stemming from the conference, this article will now be coming out in the summer of 2025. Even though the article charts the ‘biography’ of this mazer from the 14th to the 21st centuries from ‘everyday object’ to relic in both senses, drawing on the ideas of Daniel Miller, Igor Kopytoff and David Lowenthal, for the purposes here I’m just going to mention a little about its life after the arrival of the railways. For it was the railways that opened Canterbury and the surrounding area to day trippers from London and to those staying at the county’s new seaside resorts. Many of these visitors were keen to see the renovations taking place at Canterbury Cathedral, as well as attend afternoon Sunday sermons there, and even though donations from such people did not make a marked contribution to the cathedral’s fabric fund, it all helped.

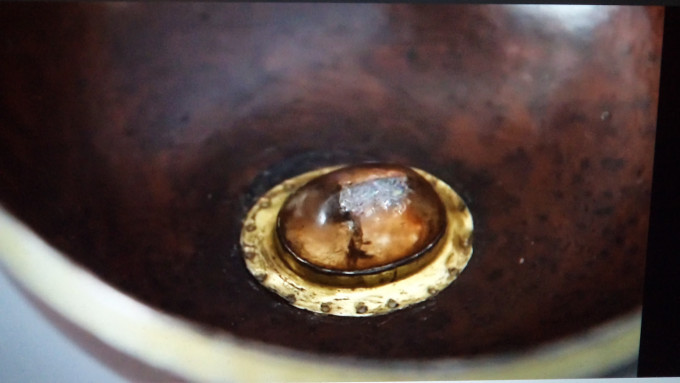

It seems likely the authorities at St Nicholas’ hospital, as at other historic establishments, watched these innovations with interest, especially because the houses for the hospital residents were in poor repair. Consequently, the idea of attracting genteel Victorian and later Edwardian tourists to Harbledown to view the hospital, its Norman chapel and its ‘Black Prince’s Well’ after a gentle river-side stroll from Canterbury was promoted. Another aspect seen as attractive was the hospital’s collection of historic artefacts including the ‘Becket mazer’ which was said to have the jewel from Becket’s shoe buckle at its centre. Indeed, as late as 1908 there is evidence that the authorities were still claiming that they had Becket’s shoe and having such relics had the potential to illicit donations in return for being able to view these curios.

Presumably, the hospital’s collections of mazers and other artefacts continued to attract interest and those who wished to see them could freely make an appointment into the 1960s. Yet in 1968 the Becket mazer alongside the hospital’s other early 14th-century mazers was transferred to the Victoria & Albert Museum, not because of its devotional value but rather it like the others were rare survivals which required protection. Nevertheless, the timing is interesting being two years before the 800th anniversary of Becket’s murder and even though the Dean and Chapter at Canterbury were intending to have a small exhibition to mark this event, nobody seems to have given any thought to the Becket mazer in London.

Indeed, it was in 1978 that the mazers returned ‘home’, even though they had been on indefinite loan, and the impetus for this seemingly came from London not Canterbury. It seems that the hospital trustees were unsure what to do with them and they were open to them going on loan to the cathedral. However, the cathedral community was seemingly caught up in other matters and did not take up this offer. The trustees decided to look elsewhere to provide security for their collection, and they found that the city council was more amenable to take most of the mazers on loan, firstly as part of the heritage collection at the Beaney and then from 1987 until its closure at the Canterbury Heritage Museum, after which they went into storage.

The ‘Becket mazer’ was detached from its fellows, which it had perhaps been with since 1546, and instead joined other diocesan artefacts in the cathedral Treasury Exhibition in the western crypt. It remained there until the exhibition also closed and it too went into storage, the catalogue entry on the cathedral’s website calling it ‘a curious object that gives us a glimpse into medieval pilgrimage and the history of Becket’. Currently, this is the end of the story, but in thinking about things from the past, I think it is worth bearing in mind that we cannot see objects as they were seen by our ancestors because we cannot unknow what we know and secondly any attempt to give meaning in the present to objects from the past needs to recognise that ‘they do things differently there’. Therefore, I hope the biography continues, taking account of the point from David Lowenthal that ‘the past informs the present [and] that its relics [such as the mazer] are crucial to our identity’.

Next week I’ll be reporting on Maureen’s presentation to the Kent History Postgraduates, which will be our first meeting of 2025.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1393

1393