Yesterday I joined about a hundred people in Old Sessions House at Canterbury Christ Church for the conference organised by Professor Louise Wilkinson, in conjunction with Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, entitled ‘Magna Carta, King John and the Civil War in Kent’. Proceedings were opened by the Revd Christopher Irvine, who is Canon Librarian at Canterbury Cathedral. He reminded the audience just how many Magna Carta events are and will be happening in and around Canterbury and just how important the city, its cathedral and archbishop had been in 1215. This set the scene for the opening session on ‘The Church’ in which the first speaker was Dr Sophie Ambler from the University of East Anglia. Her paper on ‘Pope Innocent III and the Interdict’ highlighted the effect the interdict would have had on the lay people of England. She conjured up a world where parish priests had shut the church doors, no longer celebrated Mass and on Sundays and feast days summoned their parishioners to hear a sermon at these same locked doors. However, perhaps even more stark was the vision of laypeople being buried anywhere but in consecrated ground, while the clergy were ‘buried’ in trees above consecrated ground, the bodies of lay and cleric alike exhumed or whatever you did from a tree when six years later the interdict was lifted. As she also noted the absence of church bells would have totally altered the soundscape, an exceedingly disconcerting change that would have affected rural and urban dwellers equally hard because amongst other things it was the bells that indicated the time of day. In this context it is worth noting that even after the introduction of clocks in Kent, especially in parish churches, time was recorded in contemporary documents as ‘six of the bell’ rather than six o’clock as became common thereafter.

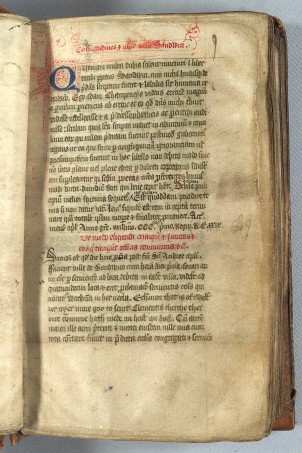

KHLC: Sa/LC1 first page of the earliest surviving copy of Sandwich custumal

copyright: Sandwich Town Council, held at the Kent History Library Centre

Dr Ambler was followed by Professor Nicholas Vincent, also from UEA, who spoke on ‘Stephen and Simon Langton: Magna Carta’s True Authors?’. He drew attention to Stephen Langton’s educational background, including his time at the University of Paris and his several decades as a teacher, when amongst other activities he was writing copious biblical commentaries, but not on the Book of Psalms. As Professor Vincent noted, the Bible was seen as a political text, it was a theatre of moral examples covering topics such as inadequate ‘modern’ kingship and the importance of the law. Taking this as his background about the new archbishop, he went on to consider two interesting aspects of Stephen Langton’s character, his understanding and use of numerical spiritual symbolism and his likely input with regard to particular clauses in Magna Carta. Just to give you a flavour of this, I’ll give one example of each. Taking the symbolic numbers first, he noted that the figure of twenty-five barons who were to act as Magna Carta’s ‘policemen’ to ensure John kept to its terms can be seen as the square of five, the number of the laws of Moses. Regarding the clauses, obviously there is the importance of the first, but I want to mention a more prosaic example that covered the removal of fish weirs from the Thames and Medway. Now their removal from the Thames was for the benefit of the London citizens, but the Medway presumably related in large part to Archbishop Langton’s own interests in the area, for as a major landholder there such weirs would have disrupted river traffic and thus archiepiscopal concerns at Maidstone. And with this link it is worth mentioning that Sir Robert Worcester concluded this session before coffee by alerting his audience to, amongst other things, the issue this year of a set of Magna Carta commemorative stamps.

After coffee the audience was suitably refreshed and were eager to hear Professor Louise Wilkinson’s lecture on ‘Canterbury in the Age of King John’. She drew attention to what can be gleaned from the royal Pipe and Fine Rolls, now held at The National Archives at Kew, as well as the monumental work of William Urry, the former cathedral archivist, whose Canterbury under the Angevin Kings with its maps are a treasure trove of detailed analysis of rentals, charters and other documents from the local archives. Among the examples Professor Wilkinson gave were the likelihood that Isabella of Gloucester was buried in Canterbury Cathedral in 1217. Isabella had a chequered married life, because having in effect been cast off by King John she was later married to Hubert de Burgh, who would be mentioned on several occasions later in the programme. Another local person from King John’s Canterbury was Terric the Goldsmith who was exceedingly wealthy, although perhaps not on the scale of Jacob the Jew whose property lies under the Abode Hotel on the corner of the High Street and Stour Street. But to return to Terric, he was involved in the several royal exchanges, not just Canterbury but also including Canterbury’s great archiepiscopal ‘rival’: York. So even though for some John’s reign was not good news, for others it offered commercial and other opportunities.

The audience was next treated to Professor David Carpenter’s narrative regarding the identifying of ‘Canterbury’s Magna Carta’. This piece of detective work rests largely on a close reading of the text, comparing a nineteenth-century copy of the original charter, which is now sadly in a very poor state at the British Library, with a late thirteenth-century copy of the charter in a Christ Church Priory Register. You can read more about the uncovering of its identity on the Magna Carta Project website and I will confine my remarks here to the point that its early dissemination, particularly in the south of the country away from the territories controlled by the rebel barons was through churchmen, the bishops rather than John’s sheriffs, and thus it is perhaps hardly surprising that of the four survivors, three are linked to the cathedral communities of Salisbury, Lincoln and now Canterbury. After this satisfying session where we also learnt that even distinguished professors can get on to the wrong train and thus see more of Woking than they would ever wish, the audience headed out of the lecture theatre for lunch.

The first afternoon session saw a change of focus to consider examples of rebellion. Dr Hugh Doherty, the final member of UEA’s triumvirate, spoke under the intriguing title of ‘The Lady, the Bear, and the Politics of Baronial London’. This paper explored the real and symbolic value placed on tournaments and, in particular, the monastic chronicler Roger of Wendover’s likely use of correspondence provided by William de Aubigny, Earl of Arundel. Again I am going to just pick out a couple of points that especially interested me, firstly after 1194 it was decreed that certain areas could be used to hold tournaments, including Stamford and a site near Hounslow, but nowhere else, and secondly that tournaments were held on Mondays or Tuesdays. The letter involving the bear stated that the tournament venue had been moved from Stamford to this place just outside London and the prize would be a bear given by a lady. However neither the identity of the lady nor the fate of the bear were recorded, but, as Dr Doherty noted, the rebel barons’ greater interest in such sports was at odds with what should have been their greater duty to their fellow rebel lords (and to God), that is those besieged in Rochester Castle under William’s leadership. The rescue force from the rebel stronghold of London to Rochester was ‘put off by a southern wind’ and so turned back soon after leaving the capital, thus leaving William and his men to their fate as they were besieged by King John and his forces, a sad indictment of the absence of baronial vigour as Roger of Wendover saw it.

Keeping with the theme of baronial activity, or inactivity, in the county, Sean McGlynn examined several episodes from ‘The Magna Carta Civil War in Kent’. In particular he discussed the successful sieges from John’s view at Rochester, which eventually after several weeks produced the rebel garrison’s surrender, and at Dover, where John’s commander Hubert de Burgh held out against Prince Louis and his French forces camped outside the castle’s northern walls, the castle remaining in royalist hands throughout the war. This was interesting but I want to draw your attention to another part of his talk where he explored the activities of Willekin of the Weald. Willekin’s band of archers was an important guerrilla force on the side of the young King Henry III in what is sometimes known as the ‘Sussex Campaign’ against Prince Louis and his forces holed up in Winchelsea in early 1217. Not that these Wealden bowmen were the only royalists involved, both William Marshal and Philip of Aubigny led forces in and around Rye blockading Louis’ escape, but their activities are especially interesting in terms of their social status. The documented involvement of Willekin’s band highlights those below the elite in the civil war, as well as offering a possible southern addition to what would become the legends of Robin Hood in later medieval England.

Prince Louis, too, had what might be described as a colourful character among his men, and Eustace the Monk was well to the fore in my talk on the Battle of Sandwich, a sea battle that has been described as ‘worthy of the first place in the list of British naval successes’. Even though Eustace swapped sides and operated on his own account when it suited him, terrorising shipping in the Channel and plundering ships from the Cinque Ports when he could, in 1217 he was working for Louis and the rebel barons. In the summer of 1217 he was engaged as the naval commander to bring a relieving force of knights to join Louis in London. Having left Calais, the French ships sailed northwards around the Kent coast where they were met by a smaller fleet from Sandwich and the other Cinque Ports. However the English did had a larger proportion of big ships among their out-numbered force, including William Marshal’s cog. Without going into details, it is perhaps interesting to note that the French were the victims of chemical warfare – the use of quick lime hurled down from great pots which then turned to slaked lime when it reacted violently with the water. Eustace, aboard the French flagship, fought ferociously but was captured and executed, his death demoralising the French. Thereafter, even though the other great French ships escaped, the English took the majority of the smaller vessels, killing most aboard and gathering the booty. Some of the booty is documented as having been used to found a hospital – St Bartholomew’s to accommodate the town’s poor. Furthermore, and moving on in time it is feasible that the town’s copy of the reissued Magna Carta by Edward I, recently discovered by Dr Mark Bateson at the Kent History Library Centre, can be linked to the construction of the Sandwich custumal of 1301, which included the hospital’s custumal. Thus the battle, hospital, custumal and Magna Carta are in many ways inseparably connected – part of the negotiating process for greater civic autonomy between town and Crown and important in the construction of civic identity.

The final lecture in the second session on rebellion was given by Richard Eales. His topic, the baronial conflict of the 1260s, drew on his expertise regarding the political circumstances of Henry III’s reign, and more particularly his considerable research on Kent’s royal castles. As he noted, this year is also a significant anniversary for Simon de Montfort’s activities regarding parliament and thus is an appropriate topic at a conference on Magna Carta and Kent. Moreover, events in the county need to be seen both in terms of its location vis-à-vis continental Europe, but equally with respect to people and politics further inland. For the Church’s dominance in terms of landholding in the county meant that its lords were deeply involved in national politics and of the lay lords only the Clare family of Tonbridge were great magnates, yet whose main power base was beyond the county boundary. Thus, what happened in Kent mattered to those in other parts of the kingdom, and what happened in other parts of the kingdom mattered to those in Kent. Among the events he discussed was the second siege of Rochester, about which we know far less than the first except in terms of what the garrison ate daily; and the de Montforts’ ‘last stand’ at Dover Castle, a far stronger and impressive fortress on which the Angevin kings had lavished vast funds. This provided a fitting conclusion to a fascinating day, and to round off proceedings Professor Wilkinson thanked her postgraduate helpers who had worked tirelessly throughout the day, Cressida Williams from Canterbury Cathedral Archives who had worked with her on the Magna Carta exhibition at the city’s Beaney Library, and her colleagues at Canterbury Christ Church, Dr Leonie Hicks and Diane Heath who had chaired sessions and also helped in other ways. Now I appreciate this is quite a bit longer than normal, but it seemed a good idea to offer a snap shot of each of the lectures given yesterday because the conference was a major event in the Centre’s calendar.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1822

1822