Firstly, thanks very much to those who came to the Canterbury Historical Association Lyle Lecture last night (Thursday), which honours Marjorie and Lawrence Lyle, absolute stalwarts of so many organisations in Canterbury and east Kent, and who were historians and authors in their own right.

It was great to see the Clagett auditorium almost at capacity on a cold February evening and it is a credit to the Canterbury branch that they have such a keen membership. Furthermore, as Julian Waltho said, who was chairing the meeting, Marjorie and Lawrence are so well known and respected and a talk on a Canterbury topic is similarly a tremendous draw that an audience of this size might indeed be expected. Also, migration is a ‘hot’ topic, indeed hotter than I had expected when I suggested it several months ago bearing in mind recent events and pronouncements both in the country and the States. Now I have talked about certain aspects of the subject regarding Kent and Canterbury in the blog in the past which means I’ll aim to bring in different examples here, as well as start by mentioning some of the broader issues and why economic migrants in 15th-century Canterbury were apparently not viewed antagonistically, except to a limited degree in the last decades of the century. Even then this seems to have been minor, especially compared to actions by some Londoners on specific occasions concerning Flemings, or Hanseatic merchants at the Steelyard.

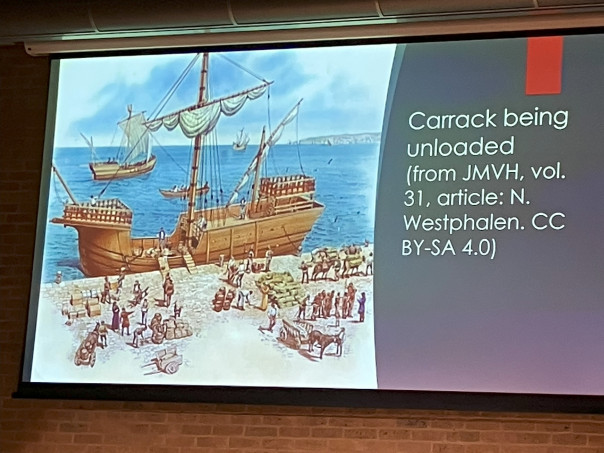

To provide a context, I thought it was important to note that although the numbers of aliens arriving and residing in Canterbury was not constant over the century, there are several underlying factors in operation including the city’s position in relation to the Channel ports and London, the Narrow Seas seen as a highway not a barrier, Canterbury’s location within the rich agrarian hinterland of east Kent, its status as a major ecclesiastical centre and its role as an international pilgrimage destination. Other potential ‘pull’ factors, although potentially being ‘push’ issues too was the incidence of plague and that the city like other places throughout the century was continuing to experience devastating outbreaks of plague about once per decade. And it is a simple equation, urban communities need people – as producers certainly but equally as consumers – aliens, like migrants from other parts of Kent and further afield to a degree at least replenished the city’s population. Indeed, Canterbury from the late 14th-century poll tax returns and the early 16th-century lay subsidy records was seemingly able to maintain its size between these two dates, something some other English towns were unable to achieve.

This is not to say everything was plain sailing because while the century’s third and fourth decades were especially buoyant concerning aliens settling in Canterbury, the 1440s and 1450s saw a downturn. Presumably this reflects the economic problems of the mid-century depression, the increasingly volatile political situation and the devastating outbreak of plague in 1457. There was a return to higher figures in the 1460s and 1480s, reflecting perhaps the more stable political situation and the relative buoyancy of the city’s economy in contrast to the intervening decade. The marked fall in the 1490s may in part have been due to local problems affecting cloth making, which prompted the city authorities to engage in several protectionist policies, including their involvement in the issuing of various craft guild ordinances. For example, even though these guilds do not appear to have been especially powerful or numerous in Canterbury, or incidentally in other Kentish towns either, probably due to the relatively small size of these urban centres, at Canterbury the chief men of the smiths’ guild, for example, were keen to ensure aliens and strangers could only trade in the liberty if they paid a set fee to the city chamberlains and similarly to the guild. Of course, a prime reason for the problems of the city’s broadcloth industry was the increasing production taking place in the small Wealden towns in place of Canterbury where producers could take advantage of the area’s natural resources, industrial expertise provided by Flemish immigrants and the presence of a local labour. Interestingly, this pattern would be repeated in the 16th century regarding those engaged in the Wealden iron industry.

Another aspect that might be said to have modern resonances concerns the social status of the Canterbury immigrants because from the national records 67 of the entries describe the person as a servant which is 12% of the total, and service as a category was used by the royal clerks in 1440, 1441, 1456, 1465 and especially 1488. Now do not think of service in terms of ‘Upstairs, Downstairs’ but more as a right of passage that is life-cycle servanthood where a young person would have the chance to earn a wage working often in the household of a relative, neighbour of friend of that person’s parents. They would have the chance to gain valuable skills while working – household and craft – thereby helping them in terms of marriage and as independent or employed artisans. From the national records there were mostly one or two servants in a specific household but interestingly Gerard Jonson in the 1488 listings is shown as having six male servants. He had apparently recruited his fellow countrymen, and it seems likely that they were engaged in his business. Cornelius Jonson is similarly recorded in the royal records for that year, and while it cannot be proved that they were closely related, it seems feasible. Cornelius had two servants and the clerk only recorded their forenames, but he gave the surnames of 5 of Gerard’s servants, including Herman Jonson who is likely to have been a relative sent to his kinsman to learn a trade. Although the occupations of neither Cornelius nor Gerard are noted by the royal official, the former appears to have been a shoemaker who was first fined by the Canterbury city chamberlains as an intrant in 1474 and he continued to trade in Burgate ward, although not always as a shoemaker, until 1487 before becoming a freeman by redemption in February 1489. Gerard may have been an even more successful shoemaker, also in the Burgate ward, during the same period. Moreover, albeit the surname ‘Jonson’ and its variant spellings is relatively common in the Canterbury records, as I explain by matching the central and local sources the presence of what might be a sizeable kinship group appears likely in Canterbury from the mid-century onwards. Most were shoemakers or cobblers, but a few made clothes, and Henry Jonesson was a bladesmith. They resided in several wards, but favoured Westgate and Burgate, although whether in specific neighbourhoods within these wards is unknown from the available documentary sources.

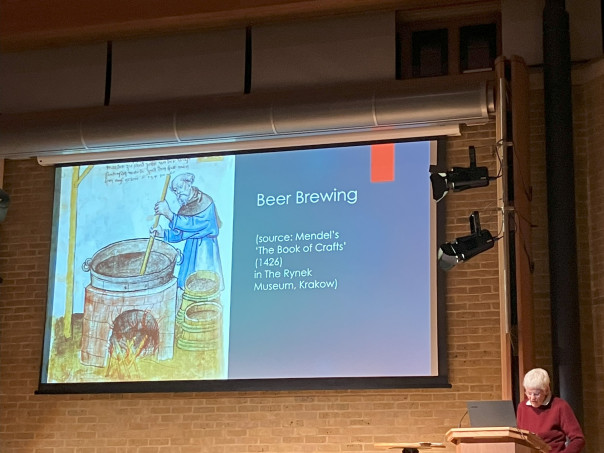

Hopefully these few examples will have given a flavour of some of the points I discussed, and it drew a wide range of very interesting questions from the audience. Among these we explored further was the growing incidence of beer brewing compared to traditional ale production, and whether hops were imported because the county’s hop gardens were a later 16th-century innovation. In a similar vein, the innovations associated with the type of cloth made and that the ‘new draperies’ were also a later development, albeit cloth mixtures do seem to have featured at some towns in Kent during the 15th century. Equally ideas about status were discussed and the importance and role of denizen status as well as the incidence of letters of safe conduct, which I hope also gives you an idea about the level of interest in the topic seen last night. So thanks very much, too, to Professor Kenneth Fincham who gave the vote of thanks, and he is right, aspects of the history of medieval Canterbury still have much to offer.

Changing the subject, albeit the importance and role of the cross-fertilization of ideas (and probably the associated movement of craftsmen) were part of the discussions today when I met up with Dr Nikolaos Karydis (School of Architecture, University of Kent), Professor Paul Bennett (former Director of CAT) and Joel Hopkinson (Head of Estates and Fabric, Canterbury Cathedral) to discuss the work Nikos has been doing concerning exploring the phasing of the construction of the infirmary building (chapel and hall) at Christ Church Priory during the High Middle Ages. He presented us with some comparable examples that he is drawing on in conjunction with detailed surveying work and Wibert’s detailed waterworks plan to produce as closely as possible the building sequence and how this might be represented to help visitors understand what they can see today. All agreed this pilot project has great potential and we are now considering the next steps.

Finally, returning to the city itself and the idea of change – innovation, fashion, copying from elsewhere – the devastating loss of much of the front wall of ‘Canterbury Pottery’ revealed recently to passers-by the presence of mathematical tiles on this timber-framed buildings as you can see here.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1592

1592

Thank you for this marvellous report

What a pity I could not come to the lecture.well done

Thank you Philippa, I’m glad you enjoyed the report.

Sheila,

I’d like to add my thanks, as, like Philppa, I was unable to attend.

Will you be giving a similar talk to another group in the future?

PS I’ve added a some pictures of the Canterbury Pottery facade to the CHAS website. See https://www.canterbury-archaeology.org.uk/mathematical-tiles