As we are now in November, I thought I would start off this week with news of the Centre’s three evening lectures this month and next, two of which are joint events with the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust, as well as mentioning the Medieval Canterbury Weekend on 6-8 April 2018 for which tickets are already selling well. To see what is available the website is at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury and as before we hope to raise funds for the Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award.

Thus, in addition to Clive Bowley’s talk on Canterbury’s timber-framed buildings on Thursday 16 November at 7pm in Newton, Ng07, where he will reveal some hidden surprises, we have Dr John Williams MBE, the new chairman of FCAT, speaking on ‘Circular Arguments: Encounters with Roman and Early Medieval Technology’. John was for many years the County Archaeologist for KCC and during his lifetime in archaeology he has travelled in this country and abroad where he has come across the remains of a variety of early mills and other “machines”. In his talk he will look at the evidence for and the interpretation of some particularly interesting examples. This lecture will take place on Thursday 30 November at 7pm in Laud, Lg16.

Early modern belt fittings (Canterbury Heritage Museum)

Finally, for 2017, Professor Paul Bennett MBE (Director of Canterbury Archaeological Trust) will give the second part of his lecture entitled ‘From Benghazi to Canterbury: an Archaeologist’s Tale’. This lecture is in honour of Lawrence and Marjorie Lyle, friends of the Centre for Kent History and Heritage and long-time supporters of Canterbury Archaeological Trust. It will take place on Tuesday 12 December, Old Sessions House, Og46 at 7pm. Those of you who attended the first part will remember what a fascinating talk it was about Paul’s early life growing up close to the east Kent coalfields, his early forays into archaeology both in the British Isles and especially north Africa, and how his initial passion for archaeology, in some senses, led him back to Canterbury. For in joining Canterbury Archaeological Trust when Tim Tatton-Brown was the Trust’s first director, Paul had met a fellow Roman specialist and someone as equally committed to Canterbury’s archaeological heritage as a way of telling the story of the city’s past. Consequently, if any (or all) sound interesting do please come along, we at the Centre will be delighted to see you.

Early communion table in what had been the Roper chantry chapel, St Dunstan’s church.

Now I want to turn to the latest meeting of the Kent History postgraduates because we had two interesting but very different presentations, one about three polemicists who were active in Canterbury in the mid 16th century, and secondly a summary of the different forms food history has taken in recent decades. I’ll leave aside this latter piece by Jacie Cole, who is looking at how people in the Kentish countryside managed to source their food during WWII (ie ration coupons were just the beginning), for this time. However next time, following her investigation of the Canterbury City Museum archive, I shall give a report – watch this space. Instead, I concentrate on Joe O’Riordan’s MA topic, where he is looking at religious changes in Canterbury society during the decade 1555 to 1565. For his presentation he explored the lives of one ‘Catholic’, the archdeacon of Canterbury Nicholas Harpsfield and two ‘Protestant’ churchmen, John Bale and Thomas Becon. These men offer interesting case studies of the interaction between cathedral community/higher diocesan clergy and the city (and diocese) during Joe’s chosen period of study, although in some ways this needs to take into account, especially in Bale’s case, his earlier connections to Canterbury because they seem to have informed how he was viewed locally in 1560.

Canterbury’s Marian Martyrs monument.

In some ways these men also throw into sharp relief the differences between the leanings of Oxford and Cambridge universities because Harpsfield had been a graduate of Oxford, which, as Joe said, brought him into the circle surrounding Sir Thomas More and more particularly for the Canterbury connection, William Roper, More’s son-in-law, the family having the great brick house in St Dunstan’s just outside the city’s limits. The Roper gateway still survives, as does the chapel at St Dunstan’s parish church where the Roper’s had their chantry chapel. Being a sensible individual, Harpsfield left England when things got too hot during Edward VI’s reign. He returned following Mary’s accession and served as archdeacon under Reginald Pole, Mary’s Archbishop of Canterbury. As Joe noted, like so many at this time on both sides of the religious divide he was a prolific writer and among his works is Treatise on the Pretended Divorce Between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. Yet he is probably best remembered for his zeal in bringing those he saw as heretics to trial, and, where they did not recant, to execution. Indeed, the location of where the ‘Marian Martyrs’ met their fate is commemorated in Canterbury through the road name: Martyrs’ Field Road, and a memorial in a small garden on which are inscribed the names of those burned at the stake.

Harpsfield outlived his superior Cardinal Pole and his queen, and at Elizabeth’s accession he fiercely held to his views, refusing to subscribe to the use of The Book of Common Prayer, refusing to take the Oath of Succession and vigorously opposing the new archbishop, Mathew Parker. This obviously brought him on a collision course with the new Church authorities and he found himself in the Fleet prison with his brother. Over a decade later he was finally released due his seriously declining health and he died just over a year later, a fate that Joe contrasted to that given to those he had seen executed.

From Canterbury Heritage Museum – Elizabethan artefacts.

Taking one of Joe’s ‘Protestant’ polemicists, the career of John Bale is extremely interesting, although Joe is only looking at Bale’s later life, that is when he returned from exile and was given one of the prebendal stalls in Canterbury Cathedral in 1560 (he died soon after). Yet the response he received in Canterbury on his return to England at Elizabeth’s accession would seem to have its roots in his previous time in Canterbury in the late 1530s. Moreover, to take his career back even further, this ex-friar from Norwich and later Ipswich (he was the prior for a short time) had also been to Cambridge University where he presumably came into contact with those holding reformist views. Thus by 1534, a time of growing political and religious tension at Westminster and London, which was increasingly mirrored in the provinces, Bale was an ardent reformer and a writer of miracle plays that attacked the established (late medieval) Church. Such activities brought him to the attention of Thomas Cromwell, whose circle he joined not least because Cromwell understood the value of plays as a ‘propaganda’ tool. And it is this that brought Bale, or at the very least his most famous play, to Canterbury. We know from depositions (witness statements) that ‘Kynge Johan’ was performed in the locality in the late 1530s, including probably at the archdeacon’s house at St Stephen’s Hackington, that is just to the north of the city. This work is a vicious satire that attacks a wide range of Catholic doctrinal issues, as well as institutions and practices, and is known to have stirred up contrasting opinions locally.

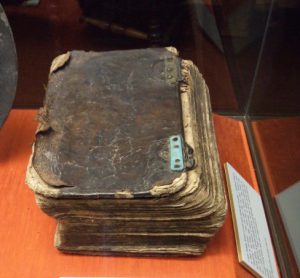

From Canterbury Heritage Museum – the La Rochelle Bible (printed in French 1588).

These seem to have resurfaced regarding attitudes towards Bale on his return to Canterbury after his second period in exile. Again, the evidence comes from depositions concerning an intriguing case involving the making of a friar’s coat that was to be used in ‘Mr Bale’s’ play. Now we know that Bale had continued to work on ‘Kynge Johan’ after its performances in the 1530s and his final revisions post-date Elizabeth’s accession because she is introduced as the character Imperial Majesty. As before a friar also features in the play, thus, even though it is conceivable Bale’s play in 1560 was another of his, it seems even more likely that the exceedingly heated argument between Hugh Pylkington and Richard Okenden that took place in John Poole’s workshop inside the cathedral precincts was about Bale’s ‘Kynge Johan’. This case, and the argument at its centre, offer a microcosm of the ideas and responses to religion and socioeconomic issues more generally in the early years of Elizabeth’s reign. For as well as the young men present, the older Pylkington and Okenden may easily have known people who had seen the performance two decades earlier and the memory of that time was seemingly still present, the play’s revival being deeply offensive to Okenden, whereas for Pylkington it offered a commercial opportunity.

Joe’s presentation sparked a considerable discussion about the role and responses to religion in the past, and the session ended by everyone wishing him all the best as he finishes writing his MA before the end of this year. Next time it will be Andrew Leach and Peter Joyce, which will take us from the 13th to the 18th centuries.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2163

2163