One lot of exciting news is that Canterbury Archaeological Trust archaeologists have uncovered the burial of Abbot John of Wheathampstead at St Alban’s Cathedral (one of the most important monasteries in the Middle Ages). For a report, see http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-beds-bucks-herts-42255514

Whether Professor Paul Bennett will mention this find in his lecture on Tuesday at Canterbury Christ Church in Old Sessions House, I am not sure, but either way I’m sure it will be a fascinating talk on his more recent times as Director of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [CAT]. If you would like to hear Paul, please come along for a 7pm start on ‘‘From Benghazi to Canterbury: an Archaeologist’s tale’ Part Two’. The lecture is in honour of Lawrence and Marjorie Lyle who over the years have done so much to make accessible the history of the city to schoolchildren, residents and visitors alike. The lecture is free and open to all, no booking required.

Another piece of news concerns the advent calendar compiled by Dr Diane Heath from previous items in the ‘Picture this …’ series which is now a three-way partnership among Canterbury Christ Church, the University of Kent and Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library. Some of you may have seen the blog Diane produced after a recent workshop held at the archives, which brought together postgraduates from both universities – a valuable exercise in itself. For those of you interested in the advent calendar, the picture for today can be found at: https://www.canterbury-cathedral.org/heritage/archives/picture-this/the-humble-potato-or-an-exotic-christmas/

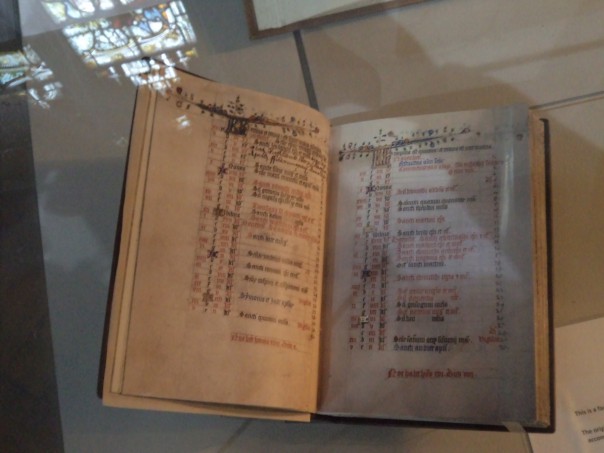

King Richard III’s Book of Hours at Leicester Cathedral – another pious prince.

This week also saw the return of Dr Michael Jones to Canterbury to give a paper to the staff-postgraduate history seminar at CCCU on the Black Prince. Michael concentrated on the Chandos Herald’s eulogistic verse history of Prince Edward of Woodstock that primarily covers the period when he was with the Prince in Aquitaine. This ‘eye-witness’ account at the heart of the narrative shows the Prince, as Michael noted, as demonstrating great prowess, a necessary attribute for a chivalric prince; his ‘love of holy Church’ that went beyond conventional piety; a man who showed personal bravery, as well as administering justice, and whose displays of largesse also went well beyond that expected of a prince of his status.

Having analysed the Herald’s particular stance and why he may have seen the Prince in this way, bearing in mind the form and outcome of the Spanish expedition as well as the Prince’s earlier exploits in France – the battles of Crecy and Poitiers, and his rule in Aquitaine, Michael then briefly turned his attention to other contemporary history writers. He also considered the Prince’s reputation among the French nobility, especially King Charles V’s response to the death of Edward, before exploring the relationship between the Prince and his father Edward III, who as king of England may be said to have adopted a more pragmatic approach to the chivalric ideals which seemingly governed the Prince’s conduct. Again, if this sounds interesting and you would like to hear more, please consult the Centre’s Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2018 website at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury where you will find Michael’s talk and lots of other exciting talks and events.

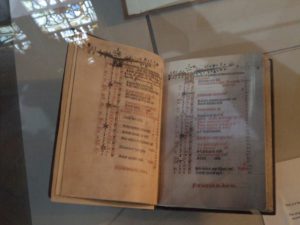

Lyminge – great case study in Kent.

Turning to other matters, yesterday I was at the University of Leicester for the AGM and winter seminar of the Medieval Settlement Research Group. Dr Andy Seaman, Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at CCCU, is the treasurer of the Research Group and he will be organising the Group’s next seminar in late April 2018 that will be held in Kent, primarily at CCCU. The theme in April will be ‘woodland and settlement’ and will have a particularly Kentish slant, and it was also interesting that the two of the papers yesterday similarly focused on research topics from Kent. The theme in Leicester was ‘animals and settlement’, the animals ranging from dogs to chickens to pigs, with one paper on sheep-related place names in Gloucestershire. However, for the purposes of this report I’ll keep to the two Kentish projects and concentrate primarily on Zoe Knapp’s assessment of what the animal bone assemblages at Lyminge can tell us about the people who lived and worked there from about the 5th to about the 8th century.

For those unfamiliar with this site, the archaeological work of Dr Gabor Thomas and his team from the University of Reading, assisted by CAT, has unearthed an exceedingly important early Anglo-Saxon set of large timber halls that demonstrate the place was one of the royal estate centres of the kings of Kent. In a society that placed great store on livestock as status symbols, in addition to the value of the hunt, Zoe’s doctoral study is revealing significant results regarding the types of animals this warrior society consumed at Lyminge, probably especially during feasts and at other celebrations. She is also looking comparatively, including West Stow, and this has highlighted the special nature of Lyminge. For unlike these other sites, the predominant animal bones found for the 5th century are pig, although whether this is a consequence of frequent, successful wild boar hunts in this woodland region or the consuming of semi-domesticated swine, I’m not sure. However, either way this is interesting and is also in marked contrast to the period after the site became the location of a religious house.

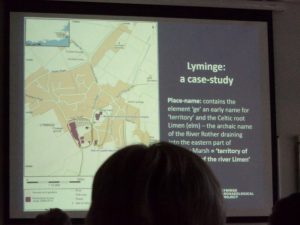

Bone assemblages from Lyminge – note spike for chickens in the monastic context [on far right]

As generally enthusiastic supporters of the Roman form of Christianity brought by Augustine and his followers in 597, the kings of Kent and later their Mercian and Wessex successors liberally endowed a series of monastic houses in Kent, of which Lyminge was one. Although some of its later history is unclear, what is apparent from the bone analysis is that the religious men and women were not consuming pig in anything like the same amount as their royal predecessors on the site. Instead, as is seen more broadly in eastern England it is sheep that were on the rise, being kept for their milk (cheese) and meat, but also for their wool. As you might expect, fish bones equally are far more abundant, but what is perhaps less expected is the significance of cod over herring. For anyone who has looked at the renders of fish in Kent according to Domesday, the sheer number of herring required by the monks of Canterbury Cathedral from their men of Sandwich appears staggering, thus the earlier preference? for cod is noteworthy. Yet even more fascinating is the sheer number of chicken bones within the bone assemblage for this later period, the pathology suggesting that the birds had generally lived in damp conditions which were over-crowded. Zoe wondered whether this can be used to assess Anglo-Saxon monastic attitudes towards animals – a rendering of Genesis that talks of dominion over all creatures, but during questions Professor Christopher Dyer posed the possibility that many of these hens were actually rent in kind provided by the house’s tenants, and thus may say more about peasant husbandry (or perhaps even attempts by tenants to render their dues as the poorest birds from their flocks).

Ashord, Kent, misericord

The audience found Zoe’s research project very exciting from the number of questions it generated, and like the rest of the Lyminge project this study has the potential to change our understanding of how early-mid Anglo-Saxon society thought and functioned. My paper had a more modest aim because I was looking at how we might explore seasonal settlement in relation to transhumance with special regard to pannage – the autumn pasturing of swine on acorns and beech mast in woodlands. The reason for examining this in Kent is the particular nature of the county – geology and geomorphology, vegetation, and post-Roman colonization and land use, which seems to have resulted in a distinctive system.

Chester Cathedral misericord, c.1380 [photo Imogen Corrigan]

However, rather than discussing the reasons for such differences, see Alan Everitt, Kenneth Witney and Stuart Brookes if you are interested, I concentrated on the swineherds as temporary settlers, looking first at the early-mid Anglo-Saxon period and then from the Norman Conquest to about 1200. The first period corresponds to the time when it was the men of the lathes who took their pigs from the ‘home’ arable lands in north, north-east and east Kent along drove ways to the Wealden forest in the south-west of the county. The latter to the time when extensive pig farming was under pressure from population growth, from the infiltration of squatters settling in the woods, from the formation of manors within the lathes that received discrete areas of swine-pasture from within the great Wealden commons, and the ever-increasing pressure on the woodland to be employed for other uses. Although I mentioned the overnight shelters that the swineherds presumably used as they moved their charges across the county, perhaps taking several days, my focus was the shelters for man and beast required once the swineherds had reached their destination, such as what they may have comprised and whether we are looking at herders (and their families?) living individually or collectively. Like Zoe’s talk, this too sparked several questions, and I intend to explore the subject further because it would seem to offer considerable scope for an investigation of the 3-way relationship among animals, humans and settlement.

Next week I hope to bring you a report on Paul Bennett’s lecture and a further advent ‘Picture this …’ link for you to explore.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1013

1013