The report this week is on Kieron Hoyle’s presentation at the Community Cinema as part of Dover Museum to a public audience that took place last night (Thursday). The report and photos has been provided by Jason Mazzocchi – many thanks Kieron and Jason.

Kieron Hoyle presented, on a balmy summer’s evening to an enthusiastic audience, a fascinating and turbulent history of the Maison Dieu. She examined the significance of this historic place as a building with its multifaceted forms from a medieval hospital (from the Latin ‘hospes’ – hospitality) to a victualling yard for the Royal Navy and significant connections between the harbour and the Crown.

The evening began with a warm welcome from Martin Crowther who introduced Kieron and chaired questions at the end of the presentation. Kieron introduced the research challenges of the Maison Dieu, particularly piecing together a vast array of documents, from national and local archives, that she has discovered on her journey and noting the challenge of bringing the history together. As a result, she is hoping that her strategy of inputting all the information into a relational database will give her access to networks and relationships that otherwise would be difficult to spot.

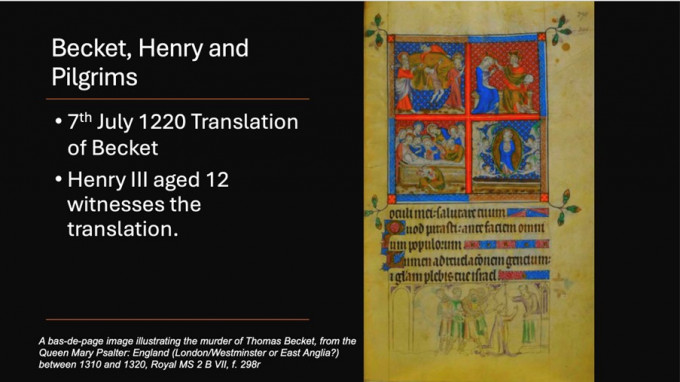

She them introduced a timeline of the foundations of the Mason Dieu which dated back to Hubert de Burgh in 1203 as a hospital for the poor pilgrims who were on pilgrimage from overseas to Becket’s tomb-shrine in Canterbury. Those who arrived in Dover with money could stay at the town’s inns, but these would not have been available to poor pilgrims. Consequently, as an act of charity Hubert’s new hospital offered accommodation for these poor pilgrims. The boy king Henry III was present at the Feast of the Translation of Becket to the new shrine in 1220 and later that decade he may have been at Dover for the dedication of the hospital’s chapel when he confirmed Hubert’s gifts to the hospital. Henry III would become well known for his piety and this included his dedication to St Thomas of Canterbury, and consequently he appropriated the role of patron of the Maison Dieu from Hubert. This might be read as a bittersweet moment – for as well as continuing to provide hospitality as a hospital for poor pilgrims throughout the rest of its medieval history, the crown also used the hospital as accommodation for the royal chancellor and his household when they were staying in Dover before travelling overseas, and as a place of retirement for aged royal retainers. Yet, as an important religious institution in the town, the master of the hospital, like the prior at St Martin’s priory, received gifts of wine from the corporation each year.

Kieron then introduced John Clarke, appointed as a Master of Maison Dieu, who first developed the ties with the development of Dover Harbour. What is revealed is a tangled web of intricate relations (which was unravelled through the meticulous evidence in the presentation), such as the Patent Rolls and money raised from renting land, such as Archers Courte in the parish of Ryver, near to the lands of the hospital, which brought in annually 26s 8d. John Clark is the first on record who, with the assistance of Henry VII, and the town’s mariners created a sea wall and haven in the shallow waters called ‘Paradise Pent’. Dover’s shallow harbour suffered from what we now call longshore drift, the prevailing movement of sands and silts being from west to east along Kent’s shoreline. This is an the very early example of the stages of developing the harbour at Dover – why? Because Dover had always been and continues to be important symbolically (and in reality) – for as Kieron stated it is the gateway to Calais and Europe.

It was the Henrician desire for a navy to protect England that mattered to the Crown and this required a good harbour at Dover. This ‘navy’, as Kieron explained, initially comprised ships used for trading and for supplying Calais, much of which took place through Dover, that could be converted for war. Consequently, the development of Dover harbour was central to the status of Dover as a key port and John Thompson (as the Maison Dieu’s final master as a pilgrim hospital), raised £500 from Crown revenues to construct two promontories and piers, but this failed to be the solution. Still the king wanted to ensure that there were ‘two eyes’ on the English Channel: Dover and Calais, which as Cardinal Worsley identified could be envisaged as a short commute between two outposts and remained the case until the loss of Calais to the French monarchy in 1558.

Kieron then explained that servicing a navy for Henry VIII was a priority and in 1544 the Maison Dieu became a victualling yard to help supply the growing navy. Dover was part of a national network of victualling yards, Dover being the fifth and smallest one (Plymouth and Portsmouth being the largest). Many of the buildings at the Maison Dieu were suitable or could be easily converted to feed the navy and offer shelter, such as the stables, chambers, kitchen, infirmary, brewhouse and bakehouse– the institution continuing as a place of hospitality and remaining important in the culture and economy of Dover.

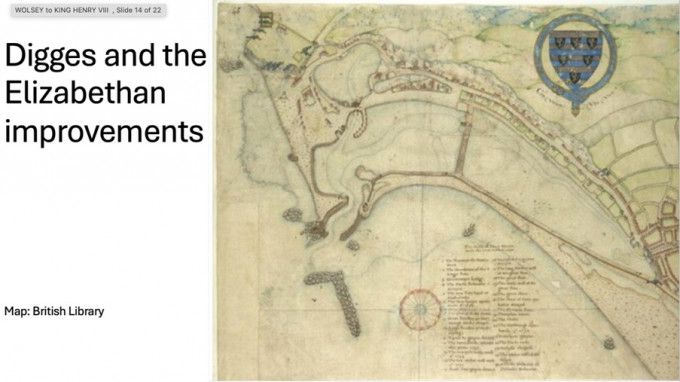

The presentation then focused on Elizabeth’s desire to maintain a strong navy – and the readiness for war, but as under previous monarchs, finding the money to sustain Dover as a harbour, was hard to source from the Crown who offered only £100 pounds, when the estimated cost was £30,000. Finding solutions to the development and security of the port almost proved a bridge too far. There were several failures, as well as ‘scandalous behaviour’. For example, John Trew in 1581 had claimed a daily rate for work on the harbour, without even a single stone having been laid, while Ferando Poyntz simply lacked any financial accountability of the money spent on the harbour’s development – claiming he never knew he had to keep accounts! It was Sir Thomas Digges, whose observations of Dutch engineers and their understanding of the principles of hydraulic engineering on Dutch maritime defences, who remedied the situation. With his expertise Digges as a master surveyor found a readied solution with a local connection – the men of Romney Marsh who constructed solid sea walls from earth and chalk, and by 1583 the development of the Harbour and its sea defences were a success.

Kieron’s presentation demonstrated how the history of the Maison Dieu is layered with multiple connections between the Crown and Dover. She eruditely examined these relationships and their importance to English and French history, and moreover provided an understanding that the development of the Maison Dieu and Dover went hand in hand – a symbiotic relationship. Kieron also signposted that this is ‘work in progress’ and she is still discovering key players in the history of the Mason Dieu, such as Edward Baeshe of Worcester, the general surveyor of the victuals for the navy and maritime affairs within the realms of England and Ireland, who may have had a significant input into the victualling yard.

The presentation was well received and plenty of questions were raised on the Maison Dieu and its architectural design, its functionality, its geographical position and wider significance to English Society and Dover in relation to the harbour and the sea. Kieron has posted this address for anyone wanting to ask further questions: maisondieuphdreserach@outlook.com

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2024

2024