I thought I would start this week by saying that the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2024 is continuing to take a good number of bookings each week and it all looks very promising. For those who haven’t seen it yet, please use either: https://ckhh.org.uk/mcw or https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury as both will get you to the MCW24 website. I’m also expanding the advertising and flyers are getting around the county, and even the country, largely due to Imogen Corrigan.

So many thanks Imogen and I shall also be looking forward to your presentation on the ‘Green Man’ at MCW24. These, ‘foliate heads’ as you rightly call them are fascinating, and I like those depicting animals too, which means the photo of the ‘Green Pig’ at Wye is back in the blog this week!

The ‘Green Dragon’ in the Franciscan Gardens is similarly looking good and is certainly green due to being covered in sedum. Drs Diane Heath and Pip Gregory were off watering the sedum today (Wednesday) and the remainder of the clay was arriving today, too. This is for the head and associated features, and like the other ‘Green Dragons’ on the CCCU campus, oyster shells will be used for claws. I’m awaiting a photo.

I am also starting to take bookings for the ‘Migrants, Merchants and Mariners in the Kentish Cinque Ports, c.1400-c.1600’ study day at Dover Museum on Saturday 23 March. This is free but booking required and for the programme and booking, please go to the Centre for Kent History and Heritage’s events page at: https://ckhh.org.uk/events where you will also find the two events linked to the Aphra Behn project in early March.

Although not until later in 2024, I did have a meeting late last week with Professor Peter Vujakovic and Dr Hadrian Cook about the Society of Landscape Studies weekend on the 28th and 29th September which will be held at Canterbury. Preparations are coming along quite well and hopefully most of the details will be in place in the next month. The theme for the weekend is ‘Sacred and Profane: the landscapes of (east) Kent’ and if this is something you might be interested in, please do save the dates. Our speakers will be geographers, archaeologists and historians, and we have some well-known Kent experts among those involved.

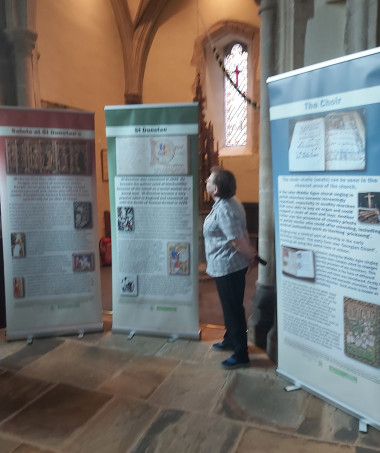

Last year it was Diane Heath who had a couple of students working with her on her NHLF-funded ‘Medieval Animals Heritage’ project as part of the second-year BA ‘Applied Humanities’ module convened by Dr John Bulaitis. The students had a great time, and the placement was highly successful. Hopefully the two students I’ll be supervising for CKHH this year will have an equally valuable and enjoyable experience as they work on the St Andrew’s church virtual exhibition. In previous years we have had students working to research and provide texts and images for actual pop-up information banners for St Mildred’s and St Dunstan’s churches, which have been very well received by the respective churches – parishioners and visitors. However, because both incarnations of St Andrew’s parish church have been demolished, it seems appropriate to have a virtual exhibition for a virtual church. What would have been good would have been if the city council had outlined the church in middle of the street, as they have done for Newingate and Ridingate – yes these are still there, and as used to be for the medieval All Saints’ church – by the Chaucer statute near Eastbridge Hospital, but I cannot see that happening. Nevertheless, if you want to know and for those who know Canterbury, it was between Pret a Manger (old Boots) and Hotel Chocolat in The Parade.

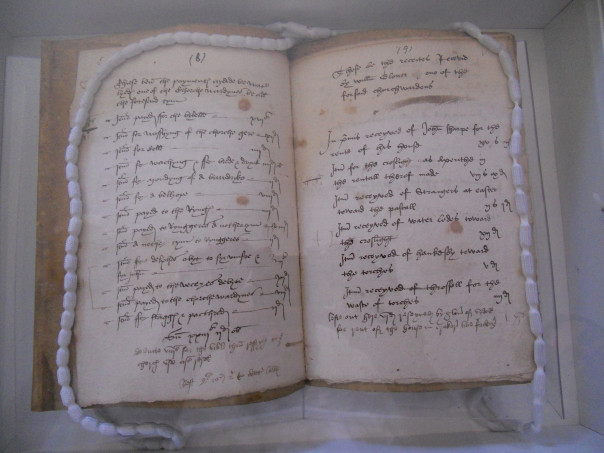

The reason I picked St Andrew’s out of the plethora of Canterbury’s medieval churches is that as well as wills for local parishioners, there is a very good set of churchwardens’ accounts, and a few visitation records for the later 15th and 16th centuries. Or to put this another way, for the late medieval and Tudor church to give you before, during and after the Reformations in terms of the reigns from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I. This provides considerable scope for compiling a ‘story’ of one parish through these turbulent times, both in terms of the particularities of St Andrew’s parish and the generalities of English society. For the two students who take it on, it also offers a chance to explore original documents in Canterbury Cathedral Archives or even the Kent History and Library Centre at Maidstone if they feel especially adventurous. Not that they won’t be working on printed primary sources much of the time because the churchwardens’ accounts and some visitation materials are available that way but seeing the ‘real’ thing is a bit special! I’ll let you know what happens with this project as things progress.

Even though the CKHH has one or two other irons in the fire, I want to hold off on them for the time being and instead stay with the Reformation period because this week I started teaching a MEMS MA module here entitled ‘Different Voices’. These ‘voices’ are primarily to be found in the archival sources for Canterbury and Kent more widely in the 16th century, many of which are to be found coming from the ecclesiastical courts. Nevertheless, I started with something a bit different because I want us throughout the term to examine the ‘different voices’ of those below the elite – commonly labelled the ‘ordinary people’, certainly me and I’m presuming most of you.

My sources this week came from the examinations conducted on behalf of Archbishop Cranmer that were conducted across the diocese of Canterbury to take evidence concerning what became known as the Prebendaries’ Plot. Following the dissolving of Christ Church Priory, the New Foundation of Canterbury Cathedral in 1541 comprised the Dean and Chapter requiring the installation of 12 prebendaries and six preachers, and among the duties of the latter, in particular, was to preach across the diocese the crown’s official position on matters of religion. Yet interestingly this group of clerics comprised evangelicals/reformers and conservatives rather than moderates, and the conservatives, moreover, saw this as an opportunity to bring down Cranmer because they believed the aged Henry VIII was more sympathetic to their doctrinal standpoint. In this they were mistaken regarding Henry’s opposition to Cranmer and instead the archbishop was given the task of investigating those plotting against him. As well as the conspiracy itself, the evidence uncovered a preaching war between the two groups from the cathedral, aided by incumbents in the parishes, but it was not solely the clergy and a significant number of laypeople were similarly involved. For this was seen as not merely a battle for preference, but a fight to the death, and beyond, for salvation – the saving of souls not only in this world, but crucially for the next.

Having published on how this unfolded generally and as a case study in the parish of Lenham, as well as talking about Canterbury, especially the parish of St Mary Northgate, in an earlier blog, I thought I would instead look very briefly at a couple of incidents reported to have taken place at St Mary’s church in Faversham. For even though the actors might be said to be clergymen – the conservative vicar there and two reformist clerics (one from the cathedral, the other from Adisham), as witnesses to such incidents and as the target of clerical wrath, it becomes clear certain parishioners were supporters of the two sides, albeit probably most parishioners to a greater or lesser degree kept quiet and watched these acrimonious exchanges unfold. Starting with Norton the vicar, although the names of the reformers who witnessed against him are not named, they were presumably local townsmen who were prepared to testify that he was failing to “declare … upon Candlemas day the true [reformist] use of bearing candles as that day, neither of Palm Sunday or Good Friday the true use of those days’ ceremonies, in bearing of palms and creeping [to] the cross”, all devotional activities that would in the past have been undertaken by the whole parish as confirmation of their community’s righteousness. Whether the witnesses against the vicar included John Tacknal is uncertain, but he was singled out by the vicar and told at confession “to use his paternoster in English no more”, while two women, Deacon’s wife and Lambe’s wife, were similarly chastised. He had also condemned others in the parish for eating white meat in Lent, while Newman, a local tanner, and his wife were rebuked for their behaviour during the same period.

For these reformists among the Faversham congregation, seeing John Scory, the cathedral evangelical, in their pulpit, especially on the parish’s feast day in 1542 must have been exceedingly welcome and they presumably would have applauded his sermon where he preached that “the dedications of material churches were instituted for the Bishops’ profits”. Keeping in the same vein, he similarly condemned the “sumptuous adorning of churches” seeing it as an anathema to the “primitive church” which “had no such copes or chalices nor other jewels, nor gildings, nor paintings of images as we have now” and his answer to such popish pomp, as he saw it, was to “sell all such things, or lay them to pledge to help the poor.” Yet others within the parish were far from happy to be treated to such a sermon, and 15 named men were quite ready to tell Cranmer’s investigation about what they saw as scandalous. Furthermore, after having heard perhaps an even more sacrilegious sermon from their standpoint, these same people were equally prepared to report the Adisham vicar to Cranmer.

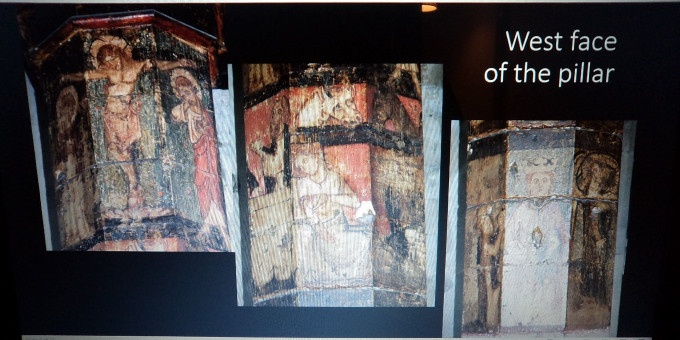

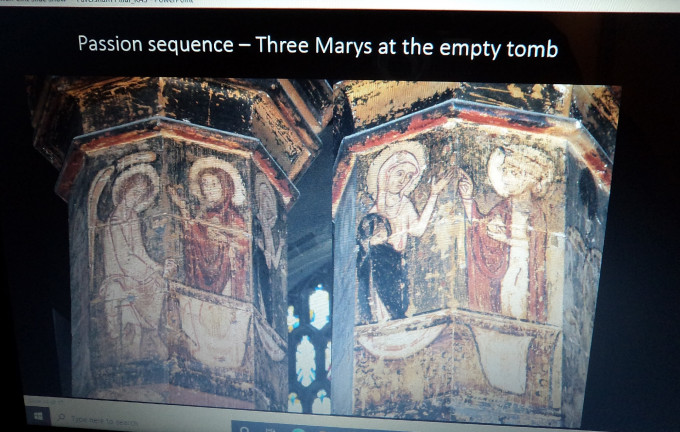

While this might be seen as no more than a glimpse of the state of affairs at St Mary’s church, Faversham, when taken with what was happening elsewhere across the diocese and the testamentary evidence over several decades both at Faversham and more widely, as well as the remarkable painted pillar in the same church, the richness and the value of Cranmer’s investigation becomes more apparent. Consequently, it was a worthwhile introduction to ‘Different Voices’ and over subsequent weeks we’ll get to hear more and other ‘voices’ from 16th-century Canterbury and Kent.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1794

1794