For this week, although the lion’s share will be Jason’s report and photos covering Kaye Sowden’s presentation at the Kent History and Library Centre on Monday of this week, I thought in the spirit of solidarity between the postgraduate history and MEMS communities at CCCU and Kent that I would mention the joint winners of the Kent Archaeological Society’s Thirsk Prize, while next week we will have the monthly presentation by Peter Joyce to the Kent History Postgraduates. However, before I come to the Thirsk Prize winners here is Jason’s report on Kaye’s talk at Maidstone.

Drawing on research for her doctoral thesis, Kaye introduced her subject to a willing and receptive audience of over 40 attendees with an interest in local and Kent history. She began her presentation on Sir Edward Dering 1st Baronet 1598–1644 by highlighting how he can be seen as a quintessential early modern gentleman who represented the community of Pluckley viz the representation of people, place and belonging. Kaye explained that there are plenty of documented records concerning the Dering family, and that Dering himself was a collector of manuscripts, books and household furnishings including portraits. The ‘numerous records he left allow great insight into everyday life in sixteenth-century Pluckley and detail his less than harmonious relationship with some of his neighbours’ – especially with members of the Bettenham family who held one of the other manors in the parish. He is also considered to have been the first person to write a records-based genealogical history of his own family, ‘and his antiquarian exploits have resulted in a love hate relationship with archivists the world over’. Consequently, he was an early modern gentleman, premised on his estate – his wealth conspicuously displayed through his superior house, his diet, his manners and his clothing.

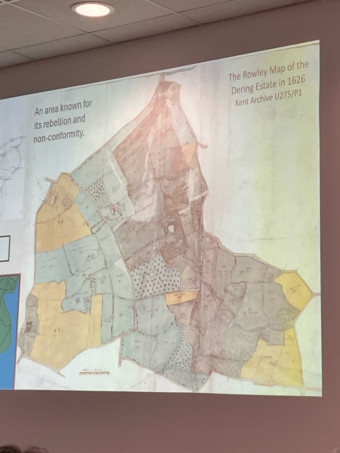

Kaye went on to explore kinship and the extended relations of the Dering family and illustrated the scale and reach of the family by displaying a map of the Dering estate, and a matrix of family ties. The Dering family held a third of the land at Pluckley. The ancestral line was explored through Richard Dering of Surrenden in Pluckley who had married Margaret Twisden, a member of a comparable Kentish family, and Richard was Edward’s grandfather. Thus, Edward Dering came from a ‘smart’ family background that was rich in cultural capital, and he was the eldest son of Sir Anthony Dering and Frances Lady Dering, daughter of Robert Bell, sometime chief baron of the exchequer. Edward was born in the Tower of London in 1598. His mother, Frances Dering had many pregnancies to live through and the births of their many children. Indeed, she was pregnant for much of her married life.

Edward Dering attended Magdalene College, Cambridge, but his primary cultural and literary interests were antiquarian studies and the theatre. He was a frequent visitor to London to see the latest plays and he bought a considerable number of playbooks. As a theatre aficionado, he was the earliest person known to have staged Shakespeare at home. This meant London culture was very much alive and well in Kent and such literary and artistic patronage was an important aspect of the networks across the county.

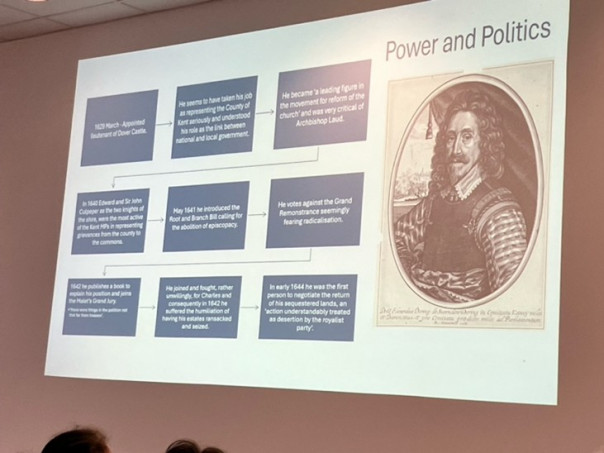

Kaye then illustrated through a series of estate maps the extent that Edward, as a landowner, established status symbols such as deer parks, for example at Eastwell. Knighted in 1619, he inherited the family property on the death of his father (the house and park of Surrenden Dering, now known as Surrenden House) in 1636. He paid punctilious attention to managing the estate and the deer population, as well as establishing the first hop garden at Little Chart, thereby highlighting his extensive interest in horticulture and the agricultural community. As already noted, Dering was also an antiquarian and spent a sum of £25 pounds on heraldry, and £27 pounds on playbooks. He took a keen interest in heraldry and the design of coats of arms. He even took to repairing the family brasses in the local parish church. He also used other ways to promote his family’s pedigree and in 1626 he commissioned new portraits of the family, spending £6 a piece on portraits of himself and his wife. Edward Dering married three times, firstly in the year he was knighted to Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Nicholas Tufton, his 2nd wife had connections to George Villers, the Duke of Buckingham, a favourite of James I and through her and even more his new mother-in-law, he sought favour at court which culminated in his purchase of a barony for the sum of £84 16s. However, Buckingham’s fall and the death of Edward’s wife curtailed his courtly ambitions, although he married again in 1629 soon after his appointment as lieutenant of Dover Castle. This appointment provided access to the castle’s muniments which seems to have been of more interest to him than the post itself and when the chance came, he gave it up to spend more time at the family home.

Nevertheless, in the years before the Civil War, Dering was also a ‘darling’ of Parliament, including negotiating petitions, but he was a believer in peace and switched allegiance – he controversially joined the Kings side in 1642. In 1644 he escaped Cromwell’s roundheads by escaping through a round window in the house. Dering is known to civil war historians as the man who changed sides, while his attempts to reform the Church and appease others resulted in his dramatic fall.

Kaye’s fascinating presentation of Sir Edward Dering, gentleman raised many questions from the audience and enquires into the Dering family and Pluckley, as well as the network of Kent’s gentry families more broadly.

Moving on to the KAS Thirsk Prize winners, it is great to be able to report that there are two joint winners who successfully completed the MEMS MA at the University of Kent last academic year. The Prize is for the top MA dissertation(s) on a Kent topic and is awarded every two years. The judges felt that Rebecca Gaylord’s and John Manley’s MA dissertations were both of a similarly very high standard and consequently it was wholly appropriate to award them the First Prize jointly. They have been invited to produce an article from their respective dissertations for KAS’s annual academic journal Archaeologia Cantiana which is edited by Jason Mazzocchi, one of the Kent History Postgraduates at CCCU, who as many of you will know is researching late Elizabethan/early Stuart Faversham for his doctorate. A second Kent History Postgraduate at CCCU is the webmaster at KAS. Jacob Scott is working on a digital history project concerning Rochester Cathedral for his doctorate and until her new post at MOLA Grace Conium, another Kent History Postgraduate and doctoral researcher (now submitted) was a KAS student ambassador.

John’s dissertation is entitled ‘Piety, Performance, and Propaganda: Situating Boxley Abbey’s Rood of Grace in Late Medieval Devotional Culture’. As he says, “The Rood of Grace was an animated crucifix attracting pilgrims from the middle of the fourteenth century to Boxley Abbey, a small Cistercian house north of Maidstone in Kent. At the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538, the Boxley Rood became notorious among Protestant reformers as evidence of monastic corruption. The reformers’ often fantastical accounts of the Rood’s mechanical capabilities have filtered down through the centuries and are still repeated uncritically in some modern English historical scholarship. Such unexamined repetition not only distorts modern conceptions of the Rood’s abilities and purpose, and colours wider perceptions of the role and practices of monastic institutions; but it also has the potential to warp the modern understanding of late-medieval religious culture so that it aligns with the allegations of superstition and idolatry that were spread by the reformers.

This dissertation will seek to present an alternative argument about the nature and purpose of the Rood. With evidence from Boxley Abbey’s own fragmentary records, from contemporary religious and secular writings, including literature and dramas, and from modern scholarship, the Rood will be situated within the context of late-medieval devotion and performance culture, both ecclesiastical and secular, examining the relationship between performer and audience, both on the dramatic scaffold and in church. The dissertation will also look at the period’s understanding of and familiarity with automata, animated statues, and machinery in both religious and secular settings. This dissertation will seek to unpick the propaganda and situate the Boxley Rood in its contemporary devotional and performance context to ascertain how devotees might have regarded the Rood and interacted with it.”

Entitled ‘Summers of Discontent: Fomenting Rebellions in Later Medieval Kent’, Rebecca explores several nationally important revolts. As she says, “On several occasions in the later Middle Ages, large numbers of Kentish people organized and rose in revolt against what they saw as endemic corruption and governmental overreach at both the local and national levels. As increased economic demands by the Crown, the encroachment on centuries-old land-holding practices and political turmoil threatened to destroy the upward social mobility unique to the Kentish commons, feelings of discontent festered and finally erupted in large-scale violence. The purpose of this essay is to examine the factors and circumstances—from geography and topography to the use of charters and other documents—that set Kent and its common people apart from the rest of England and provided the perfect conditions for fomenting rebellions. This essay examines the complex and varied reasons behind the major revolts in 1381, 1450 and 1471.

The dissertation also presents case studies of disaffected common people involved in each. The intent of these case studies is to illuminate the lives of the marginalized and little-known people who made up the core of Kentish society and to provide evidence of their possible motivations for rebellion. Through close examination and cross-referencing of extant records and documents, this essay seeks to establish heretofore unexplored social and military connections between rural and urban rebels as well as their ties to the people who became the targets of their wrath. These connections are also examined through the lens of contemporary chronicles to make the case that the rebels chose their targets carefully and strategically with their attacks being calculated and coordinated rather than random acts of indiscriminate violence. The evidence gathered in this essay will show that the common people of Kent—both rural and urban—were smart, clever, resourceful and capable of organizing resistance in the face of attempts to repress their long-held rights and their drive toward economic and social prosperity.”

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1711

1711