This week is a mix of past, present and future in that I’m mainly going to report on the ‘Church, Saints and Seals, 1150-1300’ conference that took place last weekend, but will offer a very short up-date on Lossenham Project meetings, draw you attention again to the ‘Three Days in January’ end of project conference, note that Dr Lily Hawker-Yates’ MOLA exhibition opens this week, mention that last Thursday, Jason Mazzocchi and I, on behalf of CKHH, attended a meeting at Faversham where representatives from a wide range of history and heritage groups in the town discussed possible ideas for events in August 2023 under the umbrella heading of ‘Open Faversham’, and just say that Drs Diane Heath and Pip Gregory were again working with their student volunteers on the small Green Dragon.

Regarding events coming up shortly, indeed imminently in the case of the exhibition in London which Lily, a founder member of the Kent History Postgraduates, has been working on as part of her post of Communications Officer at MOLA, this is the link: https://molaheadland.com/free-exhibition-stories-of-st-jamess-burial-ground and it is open until 23 April.

Secondly, some of you may remember the NHLF-funded ‘Finding Eanswythe’ project that was run by people from History and Archaeology at CCCU with Dr Andrew Richardson: https://blogs.canterbury.ac.uk/kenthistory/st-eanswythe-found-folkestones-anglo-saxon-saint/ Well the same team of Drs Lesley Hardy, Ellie Williams and Andrew are now coming to the end of their follow-up funded project: ‘Three Days in January’. To mark this, they are holding a 1-day conference on Saturday 25 February at Canterbury Cathedral Lodge entitled ‘Translation: encounters with the sacred in objects and spaces’.

The idea is to talk further about the relationship with ancient sacred objects and to consider, in particular, how they are seen through the work of archaeology and history, so an exciting opportunity. The conference is free and for details and the booking link, please use: https://translation.eventbrite.com or contact Anna Drew: adrew@diocant.org / 07753454586.

Briefly on the Lossenham Project meetings, last week the wills group held its monthly meeting in person at Lossenham and all bar four of the eighteen strong group were there. Moreover, it was good to be able to report that we will have a further two volunteers soon because they have both done my series of palaeography workshops and are keen to join. On other matters, Sophie and Sue M led our discussion concerning whether there have been any issues about the database, while Sue M and Rebecca began the fruitful and wide-ranging discussion regarding the group’s exploration of other archival sources beyond the core Kent probate materials. A similarly fruitful discussion involving all present concerned the group’s next activities beyond the core work on the probate materials. Thus, there is progress on the writing of a series of reports/blogs for the project website and people are continuing to support Sue H and the Tenterden Museum projects for 2023 and 2024. Having had an enjoyable and productive meeting, the group greatly enjoyed the lunch provided, so thanks Bridget.

The other Lossenham Project meeting involved archaeologists and historians, and from my perspective it was great to hear from Andrew and Paul how the excavations and other archaeological work have been progressing over the winter on the two main sites. Other matters discussed included volunteer recruitment, led by Annie, as well as the type of maps that might be most useful, how the project’s website might be enhanced and how best to integrate the project’s historical and archaeological research questions. All topics generated considerable and productive discussion.

Now to the main report, it was exciting to be part of Cressida Williams’, and therefore Canterbury Cathedral’s, ‘Church, Saints and Seals’ conference which was held in conjunction with CKHH at Canterbury Christ Church and MEMS at the University of Kent. Having met the other speakers on Friday for a meal, it was excellent to meet everyone again on Saturday morning at the Cathedral Lodge with an enthusiastic audience of staff and postgraduates from both universities, and members of the public for what would be a great day.

Having welcomed all, Cressida noted that this conference had begun life back in 2018, having been scheduled to be part of Becket 2020, and she wanted to pay tribute to the speakers who had shown such resilience in that it was now finally taking place. In the same vein, she thanked the Association of Manuscripts and Archives in Research Collections for their support. She then introduced Professor Markus Späth, who is Professor of Medieval Art History at the Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, and who has just completed a Visiting Scholar fellowship at Corpus Christi College Oxford.

Professor Späth’s presentation was fascinating as he took his audience on a journey to uncover, in many ways literally, how the Christ Church monks had come to perceive and deploy their martyred archbishop – Becket as seal. Yet, even if they may have been seen to be pretty quick off the mark in terms of the dispensing of ‘Becket Water’ and depicting the miracles in the new stained-glass windows, the monastery continued to use its old seal matrix. Thus, while other religious institutions by about 1210, including St Thomas’ Hospital in Bolton, had started employing the iconic image of Becket’s martyrdom on their seals, Christ Church did not.

Yet, as Markus was keen to point out, the monks were aware and sort to make use of visual representations of Becket’s bloody martyrdom in various ways, including a casket to hold the phials of ‘Becket Water’, the lid’s central glass ornament with red foil below mirroring what was inside the box. Furthermore, the concept of Becket as bulla, as sacrifice, as a sealed charter, as well as the link to Christ were not lost on Gervase and his contemporaries, and yet it seemingly was not until further power struggles concerning the relationship between the monks and the archbishop as their titular head that the impetus to produce a third seal matrix came to fruition around 1230. Quite how the Christ Church community conceived of the innovative idea to create a double-sided seal with the cords through the middle and an inscription on the actual rim such that either side could be displayed, provoked considerable discussion after his paper. One suggestion was that it might have come from the monastic community at Sens, and St Augustine’s in Canterbury also introduced a new double-sided seal at much the same time. However, what is clear is that the cathedral monks greatly approved of their new design, and they retained this seal until the priory’s dissolution.

For the final part of his presentation, Markus analysed the various pictorial features on both sides of the seal, especially the use of the architecture of the cathedral – Christ’s house – and the placement of figures, including Becket’s martyrdom (bottom, centre), before explaining how this seal could have been made. Even though these Canterbury seal matrices for their two cakes of wax have not survived, the Southwick matrices do, and Markus showed a short video of the process. Furthermore, for their third seal the Christ Church monks seeming always used a shade of red wax, yet again referencing Becket’s blood, as well as the holy blood of Christ, for by 1230 this juxtaposition of Becket and Christ had been in place for sixty years.

As already noted, Markus’ paper generated considerable discussion before we moved to another Canterbury seal for a joint presentation by Dr Lloyd de Beer, a curator at the British Museum who was heavily involved in the Becket 2020 exhibition there, and who is an expert on English alabaster sculptures, and Professor Sandy Heslop (University of East Anglia). Their focus was the seal on a charter dated 1278/79 from the Benedictine nunnery dedicated to the Holy Sepulchre and what they have been keen to explore is when this seal matrix design may have been first produced. The seal depicts an angel holding a palm branch in the fingers of his left hand and pointing with a finger of his right hand to the sarcophagus on which he is sitting. No other figures are shown and above the angel is part of a dome with a cross above at the top, also acting as the marker for the start of the inscription around the rim.

Taking their audience through the Gospels as seen in the Vulgate Bible, they noted the differences regarding who was present at the empty tomb, and how the tomb and other figures, including the angel are described. Such differences would seem to have given the creator of the seal matrix, just like the artists who depicted this scene in other material contexts, a choice albeit by about 900 this had become standardised as an angel and the three Marys. Nevertheless, even within this the potential to utilise different symbolic elements remained and of special significance for this seal would have been the linkage of domed canopy and ciborium, sarcophagus and altar, Christ’s body and the living presence.

Turning to the nunnery’s early history, it was founded around 1100 on land belonging to St Augustine’s Abbey and it is said to have been established by Archbishop Anselm probably with William de Cauvel, the city’s portreeve, who had married Matilda, a noblewoman and daughter of Vitalis (see the Bayeux Tapestry). Thus, the nunnery had powerful Norman patrons, which may have had a bearing on the church’s dedication and the composition of the seal. Briefly, Canterbury was one of three places with such churches from this period all located outside their respective city walls. The Easter Sunday procession and liturgy with its Quem Quaeritis that had started life as a trope – an expansive insertion into the text of the Mass, but by the late 10th century had become a more substantial dramatic piece to be enacted at the end of Matins at Benedictine churches, would have been wholly appropriate at St Sepulchre’s, perhaps also involving laypeople because the nunnery church had parochial responsibilities. In this later version, to be found in the Regularis Concordia (c. 970), the directions say the ‘angel’ at the tomb holds a palm branch, echoing the nunnery seal.

Among the places Anselm is likely to have visited, as part of his itinerary in the late 1090s as inspiration for his new crypt and stained glass at Canterbury, is the ‘home’ of Benedictine monasticism, Monte Cassino, and this may have extended to the design for the nunnery seal. Additionally, the ‘success’ of the First Crusade might be said to have brought home (to western Europe) in all senses the importance and immediacy of the holy locations in Jerusalem. From older (undated) documents an earlier version of the nunnery seal is known and the elements are the same. Thus, this may mean in terms of design that what we have takes us back to the beginnings of this Benedictine nunnery. Furthermore, it is equally feasible that there were craftsmen in Canterbury at the time who were capable of undertaking such fine work – artistically and spiritually, an exciting proposition.

After an excellent lunch, we reconvened for something different, moving to the use of seals by laypeople. Dr Philippa Hoskin, who had been the Principal Investigator of the AHRC-funded Imprint project that had examined hand marks on medieval seals, and who is the Director of the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College Cambridge, took us on a journey to explore the process of (mis-)using seals in practice and how this affects personal identity. She started with a fascinating case from the York church courts about an accusation concerning the forgery of a seal, thereby highlighting the relationship between seals and personal integrity and honour, and the concept of authentication of a person’s identity. She then went on to consider Bracton’s statement that ‘a wife and a seal may be deemed equals’ when considered in legal terms because just as a wife was integral to her husband’s assets and thus part of his responsibility, requiring him to guard her against ‘misuse’, so was his seal, for in each case if misuse occurred that was the husband’s fault, and the transaction or other event was still legally binding.

With this as the context, Philippa offered another fascinating case that shows such misuse was not only to be found in lay society but was equally of concern and an issue in the Church, taking the famous misuse of seals which occurred in the household of the bishop of Exeter in 1257. For as he lay dying his chaplain and others were busy drafting charters and sealing them with the bishop’s seal, thereby benefitting themselves, such charters deemed valid in law provided they had been sealed before the bishop actually died even though he knew nothing about them. Nonetheless, the increasing administrative pressure on bishops meant that there was a growing reliance on others, bishops needing to delegate such responsibilities as issuing and sealing documents made in their name. Indeed, a mark of St Hugh of Lincoln’s sanctity was that he actually read and was physically present when his episcopal documents were sealed! As a way of further highlighting such issues about absence and presence when documents were sealed, Philippa offered a final comparative case study from the Imprints project to demonstrate that there were regional differences between Hereford and Exeter regarding the perceived necessity or otherwise to seal physically, as seen by hand palm prints on the back of seals.

Moving from ideas about process, the next presentation by Dr Paul Dryburgh (The National Archives) provided an excellent introduction to the vast collection of seal impressions at TNA (they don’t hold any seal matrices, they are at the British Museum). Even though they hold some great royal seals, it is, of course, sealed documents received by the crown that form by far the greatest part of these governmental archives, and a large part of these are ecclesiastical. Moreover, another part of this section of the TNA collection comes from seals of religious houses caught up in the changes wrought by the Reformation that found their way into the Court of Augmentations.

Having given his audience a good insight into the scope of the TNA’s holdings, Paul offered a clear description of the various catalogues and other finding aids available. These go from the different card catalogues that have now been digitised and can be downloaded, to printed catalogues, to seals on the ancient deeds from A to P up to 1603, to the Duchy of Lancaster seals, the subject of a pilot project, and finally another digital project covering a database and images of 8000 seal moulds. Paul finished his presentation by going through a few examples to demonstrate how these resources might be accessed by researchers.

For the final presentation, we moved back to Canterbury and the second seal of St Gregory’s Priory because I wanted to explore with the audience how and why the Augustinian priory, founded in 1133, had employed various devices to (re-)create the house’s identity a century later at a time of difficulty, the priory having suffered a second damaging fire. To do this, I borrowed Amy Remensnyder’s concept of ‘imaginative memory’ (where monastic communities ‘constructing these images [of their foundation] believed in them at some level’) to examine the canons’ creative use of their claim to the relics of St Mildred, an Anglo-Saxon royal Kentish virgin saint also claimed by St Augustine’s Abbey, which included the ‘elevation’ of her relics and those of significant others at the priory in 1224.

Having given a brief summary of the priory’s predecessor, a guild of priests and clerks established by Archbishop Lanfranc, and the priory’s early history, I discussed the elements within the ‘foundation’ charter inherited from the guild: Lanfranc had established St Gregory’s for his soul and that of King William, the house receiving the relics of the virgin saints St Eadburg and St Mildred, and the body of Ethelburg, queen of Northumbria, who was said to be St Eadburg’s sister, the relics having been in the church of Lyminge from ancient times, its inclusion in the priory’s cartulary before describing the design of the second seal. This depicts the central figure of Lanfranc flanked by St Eadburg and St Mildred, all under a trefoiled arch supported on slender columns with a small cross above. Together the archbishop and saints highlighted the community’s ‘glorious past’, through Lanfranc’s agency they could bridge the divide between Norman archbishop and Anglo-Saxon saint. which took St Gregory’s into the seventh century through Lyminge and to the time of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent, thereby providing authority for those living at St Gregory’s c. 1230. Thus, the canons were able to demonstrate textually and visually their house’s longevity, prestige, wealth and authenticity, it was what it claimed to be, the canons believing that ‘their’ saints and archbishop would continue to protect them and those who patronised their house – in the present and future as they had in the past.

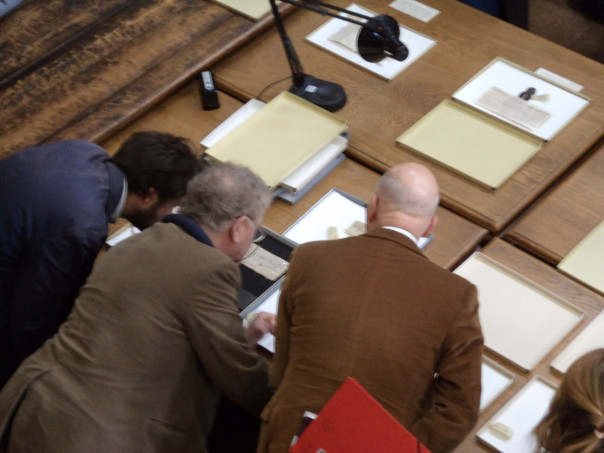

To conclude this part of the proceedings, Cressida chaired a final discussion where Diane Heath said she thought she spoke for all, saying it had been a fascinating set of presentations and a great occasion. Thereafter, everyone headed over to the cathedral archives where Cressida and her team had set up an exciting exhibition of a range of seals from the archives, including the Canterbury seals discussed earlier in the day. In addition, people had the chance to visit the conservation studio to see how the cathedral’s conservator and her team have been improving the storage of the archives’ seals collection. As you can imagine, this led to numerous discussions in the search room and studio, as well as over tea in the archives’ staff tearoom, and when Diane and I left with some delegates who wanted to see Anselm’s crypt capitals, there were still lots of conversations taking place around the archives – a measure of a highly successful day!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2388

2388