Next week will be more meetings than events, but it is great to know that preparations for Becket 2020 are continuing to develop on a wide range of fronts. Among these will be the conference at Canterbury Cathedral in November 2020, for which the plenary speakers are already in place and the call for papers will go out fairly soon. Other events planned include an even bigger Medieval Pageant than usual, a light show and events linked to several other medieval saints up and down the country – a truly national celebration of cathedral cities in England and Wales.

This leads me on very nicely to the first of this week’s events because about 150 people, including students and staff from CCCU, and guides and Friends of Canterbury Cathedral, came to hear Dr Rachel Koopmans give a superb Becket Lecture on Tuesday evening. As Professor Louise Wilkinson said in her introduction, we knew we would be in for a treat because this was the second time Rachel had been the Becket lecturer, and we were certainly not disappointed.

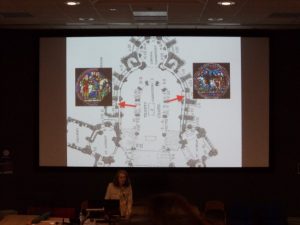

Rachel describes the two panels – to north and south in the Trinity Chapel

Taking as her way in the TV programme ‘Fake or Fortune’, Dr Koopmans set the audience a puzzle concerning which is the genuine late 12th century stained glass panel showing pilgrims on their way to Canterbury, the one on the south side of the Trinity chapel or the one on the north. In the best tradition of such programmes, Rachel put forward each item of evidence as a clever piece of detective work starting with the idea of what we know about comparable pictorial portrayals of pilgrims from this period. The answer is not much, but she did pick out the few features: the presence of the pilgrim’s staff and purse, often with a scallop shell badge denoting St James de Compostella and the staff frequently over the pilgrim’s shoulder with his cloak on it. Yet these ‘pilgrims’ are not pilgrims in the mould of those travelling to Canterbury, but sculpture or paintings of Christ or various saints who are portrayed as pilgrims. This is both good and bad. For the latter it means there is almost nothing comparable, yes, we have diagnostic objects but not the people themselves except for one example, also from the Becket Miracle windows, but he is atypical. For the former, it means this genuine panel is exceedingly important and precious.

A 19th-century photo shows the north panel pilgrims in place

Looking beyond the late 12th and 13th centuries, Rachel took her audience through the various later portrayals of pilgrims, especially those linked to Becket, from those associated with Chaucer and Lydgate to the 19th century Romantic-style of Stothard and the somewhat bizarre engraving of William Blake. Interestingly, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries the fashion for selling postcards was in full swing and the Dean & Chapter seem to have used a variety of these to promote the cathedral, a time coinciding with Samuel Caldwell jnr’s reign as the cathedral’s go-to man regarding the fabric, including the stained glass.

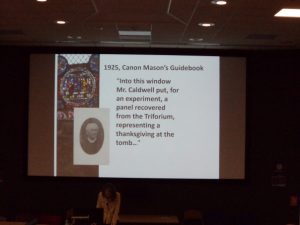

Canon Mason’s 1925 guidebook

Leaving her audience to ponder this situation, Rachel next turned to the provenance of the two pilgrim panels. She began by examining the pilgrim panel on the north side and noted that even though the earliest pictorial and documentary evidence comes from the 19th Century, in both cases it is extremely good news. In particular, Emily Williams’ detailed sketch book of the window labels this particular panel as “old” and “horse” in her notes. This both identifies the panel and tells us that Samuel Caldwell snr, an honest man, had told Emily that it was ancient and thus authentic.

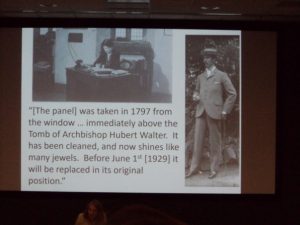

Margaret Babington and Samuel Caldwell jnr

This cannot be said of the one on the south side. Firstly, in early photos of the lower panels behind Hubert Walter’s tomb the glass is clear, whereas this is where the pilgrim panel is today. Secondly, the panel next to it was first mentioned in the cathedral guide book of 1925, where it was described as having been “recovered” from a triforium window. The pilgrims panel itself was first mentioned in the Canterbury Cathedral Chronicle volume published in April 1929. This sudden “appearance” of the panel coincided with a drive by the organisers of the Friends of Canterbury Cathedral to drum up members and greater support. The mostly likely scenario is that Samuel jnr told the Steward of the Friends, Margaret Babington, of this remarkable find, and that she was stimulated to use the panel on merchandise, including postcards, a pattern that has continued to this day.

‘Cloning’ the pilgrim rider’s horse

In her assessment of the panel in the 1981 catalogue of the cathedral’s glass, Madeline Caviness established that the panel had no medieval content. Rachel showed the audience which templates Caldwell used in his creation of the panel, including the figures and the horse itself! Unfortunately, though, the panel is still often found in promotional materials and even in scholarly publications.

Rachel and Leonie with her glass-studio team

So what about the other panel itself? This is where the project this summer funded by the Friends of Canterbury Cathedral comes in because Leonie Seliger and Rachel have been able to look at the panels from the window on the north side in the cathedral’s glass studio. Once they removed them from the window, they subjected them to very careful scrutiny using angled light and a microscope. Consequently, just as pottery experts can date pottery from points of style, wear etc., Leonie and her team have been able to do the same with the glass. Rachel shared their findings with the audience – looking at the different corrosion patterns to decide which is due to age (not acid), paint flakes, medieval shading, and perhaps the most exciting discovery of all, the presence of several distinct letters that would have read “PEREGRINI ST” – ‘pilgrims of the saint’. Thus, it is the panel on the north side which is the one created when the windows were first produced.

The border with the inscription, not a white road

In her final section, Rachel discussed why this is important in terms of the panel’s composition. For as well as having contemporary depictions of pilgrims from just after Becket’s martyrdom, we can now try to unravel how pilgrims were ‘seen’ by those behind the design of the Trinity chapel. Firstly, there are three kinds of pilgrims – riding, walking and a cripple, hardly an accident and this trinity forms a triangle through their lines of sight and actions. For example, the pilgrim on horseback is about to give a ring from his finger in alms to the cripple, while behind the mounted pilgrim one of those walking points up to the rider, thereby binding them all together on their way to Canterbury and the new saint. Finally, and something that has got Rachel and Leonie very excited is the footwear of the walking pilgrims because the decoration on their boots is very fancy, even excessively so. Consequently, they have asked themselves why and what may this denote, and any suggestions would be most welcome.

Louise chairs the Q&A session as Dean Irwin takes the roving mic to questioners

After such a fascinating talk the applause was long from a very appreciative audience and there followed a series of questions from various people. Indeed, even after Louise had closed the session after another rapturous round of applause, it was hard for Rachel to leave because a stream of people came down to the front to ask her further questions. And as a final point, Rachel thanked the Cathedral Friends for their support, and she said she and Leonie are very much hoping to take this project further because if this one panel can reveal so much, how much more is there yet to discover!

Keith discusses the second Buckland excavation

The second report in this blog will be much shorter, albeit Keith Parfitt’s joint lecture organised by the Centre and the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust was similarly extremely interesting. As Dr John Williams said, Keith (Canterbury Archaeological Trust) is so well known he needs no introduction and his knowledge concerning Dover and its hinterland is phenomenal, a statement that was borne out totally by his assessment of the various archaeological excavations that have taken place on the hill sides of the Dour valley during the last 70 years or so.

Finds from Buckland

Having provided some background information about late Roman Dover, Keith turned his attention to reviewing the two major digs that took place at Buckland/Long Hill in 1950 (by Vera Evison) and 1994 (by Keith), which together recovered not far short of 450 Anglo-Saxon graves. Moreover, as Keith mentioned, between these two sites is a railway cutting (made in 1879), which is likely to have taken out several hundred graves, albeit the records are tantalizingly ambiguous. Taking the two sites together, there would seem to be some key findings. The earlier Anglo-Saxon graves were more tightly packed than the later ones, the grave goods pointed to Frankish influence and in some ways were typically Kentish. There were kinship links, Keith remembered the DNA pointed to perhaps two brothers, often these people had died of ‘old age’ (40+-years), not in battle or other war-like activities. The number and age profile pointed to this cemetery representing the people of a village settlement, presumably in the valley bottom, who had buried their dead part way up the hillside in a place that could be seen from the settlement and to a degree re-used Bronze Age burial mounds; that is they had seemingly wanted to link their community to older communities which had similar ‘belonged’ to this landscape.

Starting on the Old Park Hill excavation

This had set Keith thinking that there might be other similar village settlements and associated hill-side cemeteries elsewhere in the Dour valley and he identified at least six potential spurs in the valley. Furthermore, this desire to link to prehistoric burial places had made Keith look at antiquarian studies of the valley, especially Hasted’s description of the barrows he had found in the parish of River close to a lime kiln on the left-hand side of the London Road. Using Hasted’s commentary, the most likely place was Old Park Hill. Not that Keith had had an opportunity immediately, but as a result of an extension to Woodside Mansion, once the home of Sir William Crundall (1847-1934) and now a care home, Keith had his first chance in 2012. This had produced some useful archaeology, including certain finds – now housed in the British Museum and the Dover Museum. However, it was not until 2017 that Keith got another opportunity and this time his team found more graves that were remarkably similar to those from the Buckland area. Listing the main characteristics, the later ones seemed to be associated with circular ring ditches, there were some but not vast amounts of grave goods, the most luxurious being an amethyst and cowrie shell (imported from the Red Sea area – an indicator of long-distance trade) necklace that presumably had been crafted by an Anglo-Saxon Dour valley resident.

The amethyst and cowrie shell necklace

The size and nature of the excavation site meant that Keith’s team found 44 graves, not the hundreds as at Buckland, but he thinks it is highly likely that there are others in the vicinity. Furthermore, looking elsewhere in the valley, with the help of maps and the writings and photographs of earlier antiquarians and archaeologists, Keith would love to investigate places such as Durham Hill, Wolverton, Sibertswell, Lousyberry Wood and Watersend because they display similar landscape features to both Buckland and Old Park Hill. Regarding these early Anglo-Saxon village settlements that would had ‘fed’ these cemeteries, Keith acknowledged that finding traces of these was far more challenging. He showed his audience a reconstruction of what such a settlement might have looked like, but as he said this was really based on one pot sherd and a great deal of imagination using evidence of what classic sunken featured buildings and long houses looked like from elsewhere, including a locally excavated site up on the Downs at Church Whitfield. Moreover, as he pointed out such downland settlements had had nothing to do with the cemeteries he had been discussing.

Potential sites Keith has his eye on

Following his fascinating talk, there were several questions including what he thought had been happening at Dover during the same early Anglo-Saxon period. To this Keith replied that the evidence so far pointed to there having been a small settlement and its most likely site was within the abandoned late Roman fort. Thus, as his audience was keen to acknowledge, Keith had indeed resolved the mystery of a lost Anglo-Saxon cemetery, as well as providing a thoughtful and well-considered examination of the Dour valley’s Anglo-Saxon past, including the potential for further archaeological investigation. So, as you can see, another busy and richly-packed week that we at the Centre hope you have enjoyed.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2073

2073