Due to it being half-term last week, I took the opportunity to visit the Canterbury Heritage Museum because now it is shut again for another month until the Easter holidays. Consequently, several of the photos this week are of the museum and link in some way to the twin themes I want to mention this week: travelling and communities.

Again, these come out of a couple of meetings I attended this week and that on Tuesday I was leading an undergraduate history workshop on early modern tombs, monuments and commemoration. However, I will come back to the tombs later and instead will start with the meeting that I was at this morning. I remember reporting on a visit to Eastbridge Hospital with Rupert Austin (Canterbury Archaeological Trust) some while ago, and it was interesting to visit the place again to see how matters are progressing concerning the renovating of this fabulous medieval and later building.

The purpose of the meeting today, and I want to thank Dr Ben Marsh of the University of Kent for suggesting to the Trustees that I should be there as well, was to think about how the local universities might become involved in the new developments at the hospital. As part of the planned refurbishment, the Trustees are considering having a mix of permanent and temporary exhibition spaces, as well as having the flexibility to use some of these same spaces for meetings, teaching and for social events. Although very much at an early stage in the process, one of the issues discussed as we walked around was what would be the underlying theme(s) running through the narrative on display to visitors in the future. From a personal perspective, the idea of travelling might be a good idea because this inclusive term could most definitely bring in pilgrimage, as well as travelling to/from/through Canterbury more broadly. Thus, in addition to the raison d’être of the hospital’s foundation and primary use in the Middle Ages – the overnight accommodation of poor (and sick) pilgrims, could be added its subsequent, albeit short-term use, to provide shelter for returning wounded soldiers and the itinerant poor – another group of travellers.

Weaving in 17th-century Canterbury, Canterbury Heritage Museum

Furthermore, thinking more of travelling and pilgrimage in terms of the journey through life, Eastbridge’s role as a school for poor boys, following Archbishop Parker’s reformation of the place in 1568 comes to mind. The role of education in society has always been seen as important, and this was certainly the case in later Tudor England, not least to provide an educated clergy, as well as lawyers and those we would now call civil servants. For those poor Eastbridge schoolboys deemed suitable, travelling to Cambridge could turn from aspiration to reality, for they had the chance to be offered a place at Corpus Christi College, a link that remains to this day.

Keeping with the idea of travelling but to a degree heading off in another direction, this meeting also brought into focus the triangle of Eastbridge Hospital, the Franciscan (Greyfriars) chapel (probably the medieval friary guest house) and the Poor Priests’ Hospital (Canterbury Heritage Museum); that is two further fabulous medieval buildings. Moreover, it is hardy accidental that physically they are close together. The poor priests took in the first Franciscan friars when they arrived in England, and Alexander of Gloucester, the master, aided them to set up their friary on the island behind the hospital. As a digression and assuming he was the same man as seems likely, Alexander of Gloucester is an interesting individual because as well as the Poor Priests’ Hospital he was also involved in the early thirteenth-century build-up of the Ospringe Maison Dieu’s lands at Staple and Wingham.

Stunning roof timbers – Canterbury Heritage Museum

Although Eastbridge was not connected to the medieval Franciscans to the same degree, today such links have been forged because the Anglican Franciscans came to Canterbury in 2003, and they live in Eastbridge’s Master’s Lodge, worshipping in the chapel and undertaking pastoral work at the hospital and in the locality. Thus for visitors and residents of Canterbury alike, through the theme of travelling these complementary and connected buildings and communities together can provide a fascinating window on to Canterbury’s past, all within a few yards of each other. Furthermore, during the summer, at least, all could be visited and enjoyed, and if (hopefully) the Canterbury Heritage Museum does survive as the Museum of Canterbury in the future, this triangle can offer a holistic history of this remarkable city.

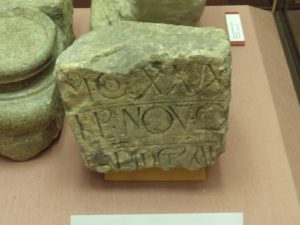

Stone commemorating the foundation of St Lawrence’s Hospital, Canterbury Heritage Museum

Turning more briefly to the second meeting, this brings me to communities, which you may have spotted had also crept into the hospitals and friary above. Timetabled under the Sustainability Research Network, it was extremely interesting to see that just about every presentation invoked the theme communities in one way or another. For universities Sustainability is a valued concept, and, for the Centre for Kent History and Heritage, perhaps this can be best interpreted through activities such as community engagement and issues related to celebrating a sense of place and heritage – thus looking backwards, but also forwards into the future. For this Centre, I decided to focus on four things. It organises events: history weekends, conferences, public lectures, and workshops; and, allied to this it encourages partnerships (including Kent Archaeological Society, Canterbury Archaeological Trust, Historical Association, Canterbury Cathedral, National Trust, Kent Archives Service, Canterbury Museums Service) with those outside the university in the study and dissemination of Kent history. Thirdly, it also encourages postgraduates inside the university in their research of Kent history topics, and finally it provides a platform, through the Centre’s website, to reach out to the world.

Thinking about the extremely interesting presentations given by people from other Research Centres at Canterbury Christ Church, it is probably feasible to find common ground with all but I’ll just mention two I think have the closest links. The most obvious is the Centre for Research on Communities and Cultures, and I was fascinated to hear about their work on the seaside photographic archive and the concept of ‘community repair’, where they are working with communities, especially in Thanet, to create a narrative of what has happened in the last thirty years. Although very different, my second is the Ecology Research Group, and albeit dormice habitat may not seem relevant, if instead that equates to researching the history and topography of a particular landscape – woodland, downland, heaths, meadows, shared foci and agendas begin to emerge. Moreover, just by being in that room yesterday to listen, discuss, network, drink coffee, and find common ground, we became a ‘community’.

The tomb of Richard Stuppeny, New Romney

Finally, I want to return to the tombs and commemoration, looking at the Stuppeny tombs of New Romney and Lydd. Without going into detail, I just want to mention what I find interesting and what we focused on in the workshop: Clement Stuppeny’s actions in the early 17th century. Even though his uncle Lawrence was presumably the lead in terms of Clement Stuppeny senior’s tomb in Lydd, I cannot believe the younger Clement was not consulted or involved in some way as the only other male member of the family still living in the town. However, when it came to Clement junior’s reconstruction of his great-grandfather’s tomb that was all his own work. For as the new (reused piece of brass) inscription states, this was Clement’s initiative. The key features of the inscription, I believe, are: a) the ‘biography’ of Richard Stuppeny, b) the ‘autobiography’ of Clement, c) the pushing back into the Catholic past of Richard by changing the date of death from 1540 to 1526, and, most importantly for the purposes of this blog, d) the ‘placing’ of his Stuppeny ancestor at the ‘centre’ of civic and community life – his tomb was where ‘mayor-making’ in New Romney took place. For Clement duty to community and family mattered, it was tangible, it reached back into the past as well as looking into the future. Moreover, presumably he expected this gift exchange would be reciprocated. Those holding civic office, too, had a responsibility to ensure that what had been ‘given’ to the town, the tomb – a form of heirloom – would be respected and cherished, not cast away, and in New Romney Clement Stuppeny’s faith was justified. Such examples from history are valuable, and in the 21st-century one might say that responsibility to and sustainability of communities comes in many forms.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1115

1115