As I expect you have gathered, June has been a very busy month full of very exciting lectures, conferences and workshops, and last week was no exception.

So while I am also looking forward to the Tithe conference next Saturday on the 17 June: www.canterbury.ac.uk/tithe – there will be tickets available on day if you haven’t already booked, this week I am reporting on events last week. These were Dr Diane Heath’s joint Centre and FCAT lecture on Nigel Wireker, an extremely interesting Canterbury monk, and the public lecture given by Professor Paul Binski on Thomas Becket. This latter event was held at Canterbury Cathedral Lodge as part of a Becket study day organised by Dr Emily Guerry (University of Kent) and colleagues from London and Cambridge, and among the participants was Professor Louise Wilkinson from the Centre at Canterbury Christ Church. These study days are part of a programme leading up to events in 2020 at the British Museum, London, and at Canterbury to mark the 850th anniversary since the murder of Archbishop Becket and the 800th anniversary since the Translation of St Thomas to the shrine in the Trinity Chapel in Canterbury Cathedral.

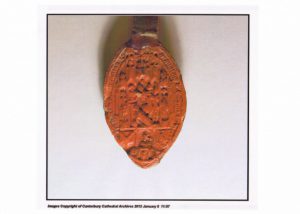

Working chronologically, I’m going to start with the Becket study day and public lecture last Tuesday. Cressida Williams, Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, hosted the study day and delegates from Cambridge, St Andrew’s, London and Canterbury gathered in the seminar room for a round of ‘quickfire’ 5-minute presentations on objects that evoke Becket in some way. This meant that we had presentations on: paintings showing the martyrdom linked to the Counter-Reformation (Lloyd de Beer); marginal manuscript drawings of Becket’s head pierced by a sword that were used in the medieval Exchequer to identify Canterbury archiepiscopal documents (Julian Luxford); a pontifical manuscript that may have belonged to Becket (Helen Gittos); an altar frontal from Spain c.1200 that seems to show the murder (Tom Nickson); part of an ampulla mould found in an archaeological excavation in Canterbury (Paul Bennett); a St Thomas ampulla and pilgrim badges (Amy Jeffs and Gabriel Byng); charters detailing gifts to St Thomas (Louise Wilkinson); Simon Sudbury’s seal showing Christ’s crucifixion and Becket’s martyrdom (me); a finger ring with what looked like a diamond and an engraving of the martyrdom – interesting in that William Chilton of Canterbury seems to have given something similar to the shrine in 1503 (Naomi Speakman); the St Thomas’ chapel on London Bridge (Alixe Bovey); panels from the Canterbury Becket stained glass (Michael Michael); and vestments that may or may not be contact relics from Sens Cathedral (Emily Guerry).

St Thomas pilgrim badges: Canterbury Heritage Museum

This diverse range of topics provoked considerable discussion in the session after coffee about what themes might be used for the London Becket exhibition in 2020, and how the international dimension of the cult might be explored to best effect. Several participants stressed the importance of material culture, and that, even though new digital representations are extremely useful, there is a fundamental value in engaging with the likely audience through the materiality of the actual objects linked to Becket. Although unintentional, such an audience response would have been seen by a casual observer if s/he had witnessed the sessions after lunch. The first of these comprised documents and objects from the Archives and Library displayed in the reading room that had a Becket link. Having experts in the room who were keen to talk about several of these was an added bonus and among the items discussed by the group were seals, of which the cathedral has an excellent collection.

The group was then treated to a visit to the stained glass studio where amongst other fascinating topics Leonie Seliger discussed the composite nature of the Becket windows in terms of medieval and modern glass, and that she has recently identified another two Becket heads as being original, making a grand total of three. I’m sure you will be interested to know that this is down to the shape of Becket’s ears. She also discussed medieval techniques for the making of particular forms of coloured glass, as well as the problems of conservation, and her audience would have stayed far longer if time had permitted. However it didn’t, which meant that after another swift cup of tea or coffee we headed into the cathedral to look at several archiepiscopal tombs, the glass of the Corona chapel and the site of the shrine. Thereafter the group dispersed, some went to Evensong, others to get further refreshment and continue the discussion before Professor Binski’s lecture.

Archbishop Sudbury’s seal – showing Becket’s martyrdom: Canterbury Cathedral Archives.

The Clagett lecture theatre at the Lodge was almost full when Emily Guerry introduced Paul Binski to the audience. As she said, he is Professor of the History of Medieval Art at Cambridge University and a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, and the Becket 2020 group is very fortunate to have his expertise. On Tuesday, the subject of his talk was ‘Thomas Becket and the medieval cult of personality’. He began by discussing how medieval culture did not envisage personality as we do today, rather there was the concept of persona – the outer – that might be closer to the idea of character in terms of a type, which might form an exemplar or its opposite – characteristics to be avoided. Such ideas were commonly deployed in what we now call morality plays such as ‘Everyman’ and ‘Mankind’, but were also present in biblical and saints’ plays where the audience was encouraged to look for types and anti- or ante-types, which employed the idea of imitation. For example, Isaac of Old Testament Abraham and Isaac fame was a type for Christ in that he too was a sacrifice, as well as showing all the characteristics of innocence, humility, obedience; and, in addition, he was a forerunner – the Old Testament fulfilled in the New.

Taking this concept of imitation and applying it to Thomas Becket, Professor Binski considered it in the light of the political situation in late 12th and early 13th century Europe that had witnessed the growth in papal power and authority, which was part of national and supranational power struggles involving the heads of many countries and proto-countries including the kings of England. Papal canonization was, in a sense, one of the weapons in the pope’s armoury. Becket’s martyrdom might have been viewed as a God-given opportunity, especially when coupled with St Thomas’ newly perceived persona of suffering, humility, even perhaps aestheticism through the louse-ridden hair shirt, which mattered for his fellow and succeeding clerics, and, also, for the ordinary people.

Thereafter, Professor Binski looked at how such ideas were harnessed by the authorities, what might be called Becket’s cult from above, as well as his cult ‘from below’ – the popular response and perpetuation of St Thomas, and how in many ways these two drivers of Thomas as international saint came together in the creation and building of the Trinity Chapel, and, indeed in many ways the whole of Canterbury Cathedral. Among the aspects Paul Binski discussed, were the multiplicity of cult centres within the cathedral linked to Becket. However, he noted that in many ways the place of the tomb in the crypt was matched, and then surpassed by the shrine in the upper chapel architecturally, topographically, and perhaps symbolically, albeit the vast majority of the recorded miracles concern the tomb in the crypt not the shrine. He also drew attention to the use of colour of the columns and the floor tiles, and how these were intended through the language of colour to signify ideas about persona, including, for example, the martyr’s close relationship to Christ.

Thought to come from St Thomas’s shrine: Canterbury Heritage Museum

Having explored several other examples, Professor Binski finished his lecture by briefly considering the relationship, as seen through such types, between sainthood and kingship. He noted that even though there are kings as martyrs, St Edmund springs to mind and, obviously from a much later date, we have the still controversial figure of Charles king and martyr, yet nonetheless kings as confessor saints might, as a type, be far closer to Henry III and his piety. Nonetheless, for the king this presented certain problems regarding popularity because whatever Henry III might have hoped for St Edward the Confessor at Westminster, he never achieved the popular following of St Thomas at Canterbury. This fascinating lecture was enjoyed by the audience from the number and breadth of the questions, and from the excited buzz afterwards – or perhaps that was the wine!

Keeping with the same period, I now want to offer a short report on Dr Diane Heath’s joint Centre and FCAT lecture on Nigel Wireker’s Speculum Stultorum or The Mirror of Fools. For those of you unfamiliar with the adventures of Burnellus the wild ass or onager, I’ll just give a quick summary. The first thing to notice about Burnellus is that he is really a hybrid creature – an onocentaur or ass-centaur because he has hands not hooves, he walks upright on his hind legs and he talks. The joke of the tale is just that poor Burnellus wants a long tail to match his long ears and he asks the foremost medical expert of the time, Galen, for advice. Galen being wise tells him he should not want to change his God-given nature but Burnellus will have none of this, so Galen gives him a mock list of the items he will need. Being an ass Burnellus sets off for Salerno to acquire the ingredients but once there is tricked into buying empty jars.

Diane highlights the importance of the Bestiary.

On his return via Lyon, Burnellus is accused of trespass by Fromundus, a Cistercian, whose fierce dogs attack Burnellus. As a result, Burnellus loses half his tail and his jars, broken in the assault. He angrily seeks recompense, which the monk promises but really is secretly intending to murder Burnellus. The ass suspects the monk of double-dealing and kicks him into the river. He is so delighted by his cleverness that he heads off to study at the Schools of Paris, Oxford not being an option at the time, and on the way meets a Sicilian pilgrim called Arnold, who tells of the rooster’s revenge (used by Chaucer). Even though Burnellus studies hard for seven years with his friends among the English students, it is all pretty fruitless because all he can say is ‘hee-haw’. Feeling that he has misspent his youth, he thinks about becoming a bishop, or a member of a religious order – no false modesty here, but decides it would be better to set up his own. Having met Galen again, the ass pours scorn on the papal curia, king’s court, bishops and abbots but then backs off somewhat and asks Galen to join his order. However, his old master catches up with him, trims his ears to match his tail and puts him back to work. The epilogue on over-ambition, ingratitude, and the wisdom of learning from the fates of others can be seen as linking to the prologue in which Nigel address William, bishop of Ely for whom he had very little time! Just as an aside, it is worth saying that almost 400 years later William Lambarde totally shared Nigel’s views on the bishop, seeing him as the oppressor of the nobility, clergy and common people through his misuse of power as Chancellor of England and Papal Legate. Yet even more tellingly Lambarde recounts the bishop’s cowardice and shame when he tried to escape disguised as a woman at Dover but was found out and ‘by certaine rude fellowes openly uncased’, although Lambarde prefers to refer to the bishop’s ‘Pecocks feathers pulled’ rather than comparing him to Nigel’s ass.

Hopefully you can see from this that it is a very engaging tale (sorry, I’ll stop the punning), but more than this Diane believes there is sufficient evidence to read the text as Nigel’s critical commentary on the events he and his fellow monks at Christ Church Priory were enduring in the decades after Becket’s martyrdom. These were the fire of 1174, but even more importantly Archbishop Baldwin and Hubert Walter’s attempts (almost successfully) to set up an archiepiscopal college at neighbouring Hackington that was to be funded, at least in part, by the priory’s almonry properties and which would include, if they got their way, St Thomas relics. Moreover, the priory community’s troubles were not over after Hubert Walter was ‘defeated’ in 1201 when Pope Innocent III decided in their favour, because there were problems over the appointment of Archbishop Langton, which led to the papal interdict on England and the monks’ exile. Nor was the Christ Church community’s difficulties over yet, instead the barons’ struggle against the king drew in the priory. Thus, the Translation in 1220, which came three years after Nigel’s death, was a fitting reconciliatory event between monarchy and Church, as well as more specifically among priory, archbishop and king.

Diane explains Becket’s legacy for the Canterbury monks.

Using the poem as text and setting it in its context, Diane then took her audience through what she believes are the telling points – Nigel’s ideas about masculinity and monks, in other words how masculine should a monk be? How should links between honour and outward show be understood? What was the relationship between long tails on asses and Englishmen, and the showiness and length of bishops’ retinues? How should masculinity and rage be understood, especially when it might be seen to be unmanly because it was tyrannical? This was a fascinating close reading of a text that appears to have been popular in the Middle Ages but has received little critical study in modern times. Consequently, it was very exciting to hear Dr Heath’s analysis and I believe she intends to publish her findings soon. Thus, as I said at the start, last week was packed with fascinating events.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1799

1799