I thought I would first bring news of the next and hopefully last online events the Centre will be running as we inch towards getting back to physical rather than virtual events. Again, please come and join us for Professor Paul Bennett’s Becket Lecture next Wednesday 16 December starting at 7pm.

Paul will be highlighting what the archaeological investigations can tell us about ‘Canterbury at the Time of Thomas Becket’. Many of these Paul has been involved with personally over the last 40 years, giving him an unparalleled knowledge of the city’s medieval past. This online lecture using Teams is free and please save the joining url: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup-join/19%3ameeting_MjkzNTM5NDItMWQ1NC00MGM3LThiZWMtMWQwYTAyODUyMmRh%40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%220320b2da-22dd-4dab-8c21-6e644ba14f13%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%225438ffb7-ff66-44f6-9ccf-cf504309571b%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d

Please either click or copy into your web browser about 5 minutes before the start time.

Then next March on Saturday 27th and Sunday 28th we will be holding our Tudors and Stuarts History Weekend, also on Teams Live Events. Matthew and Kellie are putting together the final touches to the Centre’s History Weekend web pages and to the booking pages. I am extremely excited about the terrific array of leading scholars we have for you and this time you will not need to make choices because you will be able to hear all 11 lectures, as well as the 2 free films, for the excellent price of £60. It will also be possible to book individual lectures at £7.50 each. After costs, this will help us to raise money for the Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award fund – more details I hope very shortly.

Keeping with the idea of lectures and postgraduates, I’m delighted to announce that working with the Friends of Canterbury Cathedral and the Canterbury Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (CAMEMS), the Centre is hosting six talks by CCCU Humanities and Kent MEMS former and current postgraduates. These Lunch Time Lectures will take place on Teams Live Events on Wednesdays between 1pm and 2pm, starting on Wednesday 13 January and going through to Wednesday 17 February (Ash Wednesday). These will be free and the joining url will be given out in the preceding week. We will be bringing you a diverse programme with our three CCCU talks featuring Dean Irwin discussing two Jews from medieval London, Dr Lily Hawker-Yates examining the invention of St Amphibalus and Jacqueline Stamp investigating perceptions of the Arctic in Victorian literature.

The Centre is also involved in two further collaborative initiatives. I have already mentioned Paul Carney’s and James Cook’s ‘Walkie Talkies’ and we now have the full version of ‘Walking the City Walls’. Hopefully, this will be available on the Centre’s web pages shortly, as soon as it is, I’ll let you know.

The other collaborative event is one under the leadership of Professor Carolyn Oulton as part of the International Centre for Victorian Women Writers at CCCU. Some of you may remember the Digital Kent Map project from previous blogs and the next event Carolyn is planning is a symposium on 5 May 2021 to explore the making of new connections across the county and across time. For the project is now well placed to think about ‘shared and inherited spaces’ as generations of writers and artists visit or inhabit the same locations, sequentially or at the same time. There is now a call of papers on any aspect of Kent’s cultural and literary history and topography. These might include: the curation and reinterpretation of literary heritage; literary and publishing networks; the circulation of books and manuscripts, and reinterpreting landscapes. If you are interested in contributing or finding out more, please contact Carolyn at: carolyn.oulton@canterbury.ac.uk .

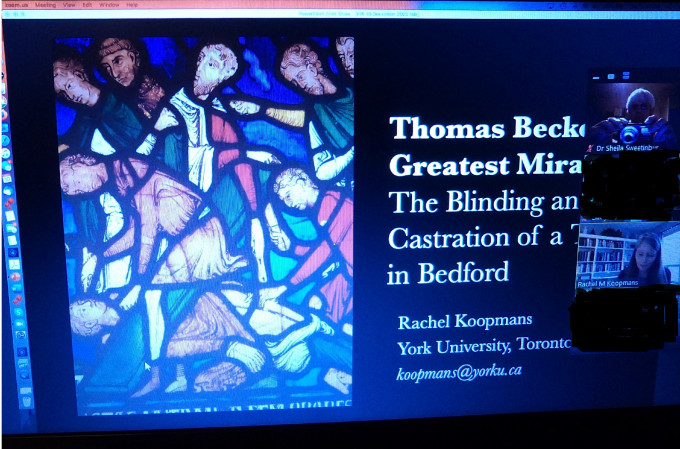

For the remainder this week, I’ll be bringing you a short report on Dr Rachel Koopmans paper for the IHR on the ‘most important’ Becket miracle, while keeping with the Becket theme, Dr Diane Heath will provide a similar report on Dr Rowan Williams’ lecture on Thomas Becket.

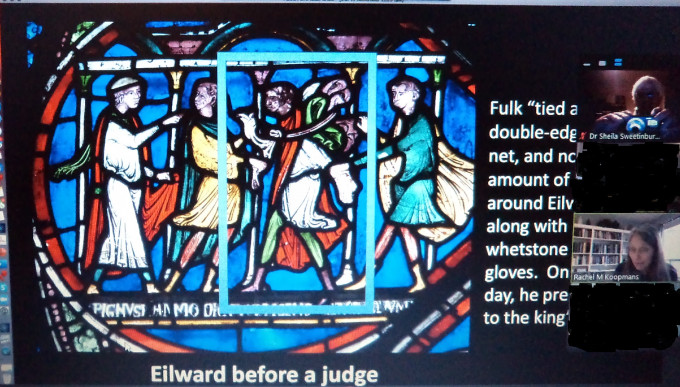

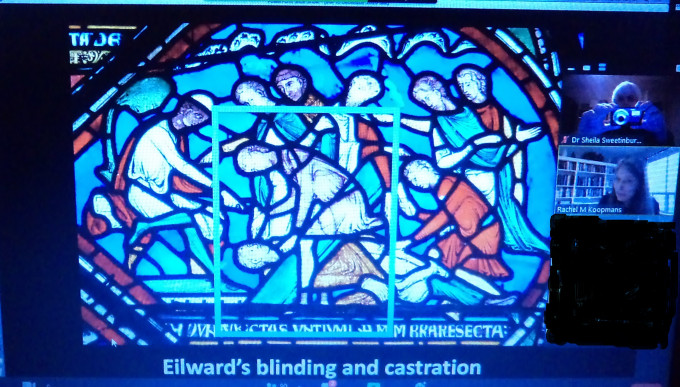

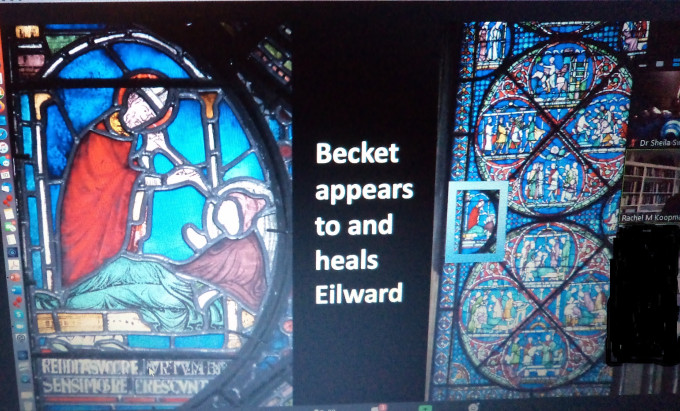

So which miracle was that special? Looking at both the documentary evidence and the stained glass in the Becket Miracle Windows at Canterbury Cathedral, Rachel believes it was Becket’s miracles for Eilward from Bedford who gained new eyes and new testicles. Eilward might be said to have been the victim of a miscarriage of (the king’s) justice because he was apparently framed in a case of theft, failed the ordeal by water because he had been baptised at Whitsun – thus could not drown, and was punished by being blinded and castrated. A local priest had told him to appeal to the recently martyred archbishop and in response Becket gave him back his sight through the gift of new eyes – they were a different colour, and he also regained his testicles. Naturally he made his pilgrimage to Canterbury to give thanks, meeting the recently restored Bishop Hugh of Durham on the way while the bishop was staying in London, a meeting that seems to have led Hugh to endorse Eilward’s miraculous recovery and publicly to set great store (politically) on the meaning of his occurrence. Indeed, Rachel thinks that Eilward’s miracle narrative may have been the catalyst for Henry II’s change of heart and his willingness to make his own pilgrimage, accept public chastisement and ritual humiliation, and endorse Thomas’ sanctity.

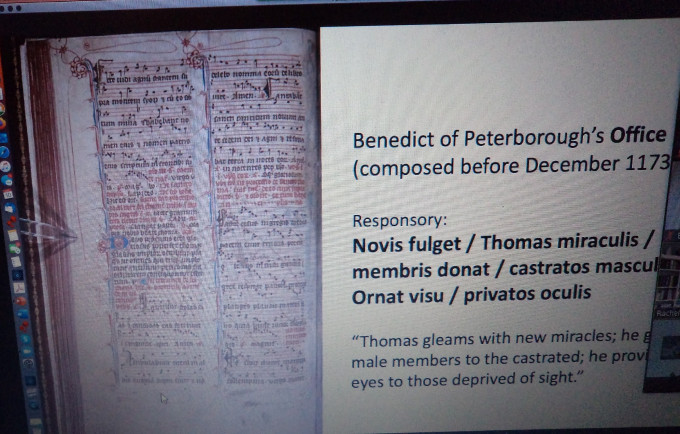

Turning to the sources, as Rachel outlined, these are both numerous and early concerning the written texts, from the testimonial letter by certain burgesses of Bedford (1171), the miracle narratives of first Benedict of Peterborough (early 1172) and then his fellow Christ Church monk William of Canterbury (late summer 1172), to the accounts in Master Robert Cricklade’s ‘Life and Miracles of Thomas’, written by 1174, and those of others including Gervase of Canterbury’s Chronicle and Gerald of Wales’ ‘Conquest of Ireland’.

Nor was this all because there were what might be called almost contemporary copycat miracles relating to castration on behalf of William of York and Wulstan of Worcester, as well as similar results for two clerics, one in England and another in France. Moreover, the reports of tail docking Becket’s horse in the run-up to the archbishop’s murder would have been similarly understood symbolically, and such actions were repeated during disputes involving late archbishops.

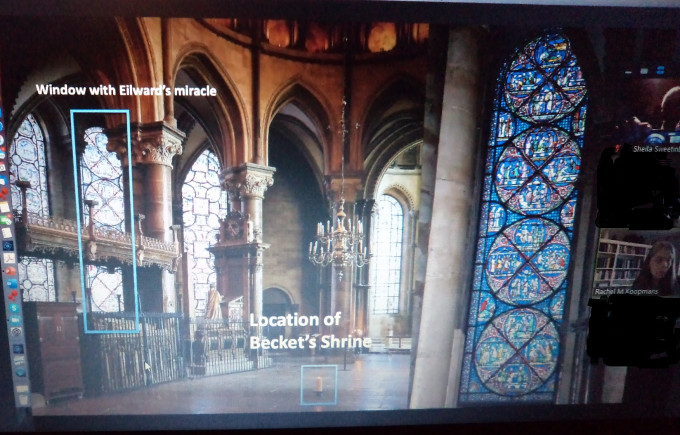

This evidence is extremely interesting, but the glass offers perhaps an even more fascinating take on Eilward’s miraculous deliverance because of the amount of time and effort that the Canterbury glaziers devoted to this miracle. Set in one of the north ambulatory windows, and incidentally the window that will feature in the British Museum Becket 2020/21 exhibition from next April to August, the arrangement and sheer number of panels devoted to these miracles for Eilward demonstrate their importance to contemporaries as a mark of Becket’s spiritual and political power in the dispute between king and Church. Furthermore, because the window is being prepared for the exhibition, Leonie Seliger at Canterbury Cathedral Glass Studio and Rachel have been able to work together again and among their discoveries is that the top panel of the series relating to Eilward does not belong there. It would seem that probably in the 19th century the top panel of this miracle narrative and that relating to the leper at the top of the window were reversed. This is significant for both narratives but just keeping to Eilward, it means Becket is shown directly intervening to help our man.

Now Rachel went into far more detail than I have here, but I just want to finish by reiterating the importance of this specific miracle narrative, including its political value for Becket’s supporters in their bid for his canonisation and his opposition to royal interference in ecclesiastical judicial matters. Additionally, this miracle seemingly continued to thrill audiences well into the 13th century, and these cultural aspects are fascinating in terms of the ideas they give regarding contemporary responses to social hierarchy, including how a ‘rustic’ with an Anglo-Saxon name (and parentage?) had the potential to bring down, metaphorically, one of the greatest medieval rulers of the age. And even more by placing this pictorial narrative in stained glass next to Becket’s intervention on a leper’s behalf, we have Becket’s Christ-like care for the lowest in society, where the last are first and the first last, as well as being ‘one in the eye’ against Henry II (and even to a degree certain of his successors).

Rachel’s fascinating paper brought a host of questions and comments, and it will be very exciting to hear more about their discoveries as she and Leonie spend more time next year examining the glass before it is put on display in London.

As promised, here is Diane’s summary of Dr Rowan Williams’ lecture: this lecture was held by The Ecclesiastical Law Society, in association with Villanova University, the University of Notre Dame, and the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral. Over four hundred people attended, including Professor Mark Hill QC, Chairman of the ELS, who welcomed the Rt Revd and Rt Hon The Lord Rowan Williams of Oystermouth, to speak on ‘Saving our Order: Thomas Becket, Henry II and the Law of Church and State.’ I confess I missed the very first three minutes due to wifi problems, so I entered the Zoom room to hear immediately that evocative phrase ‘criminous clerks.’

‘Criminous clerks’ were either priests or men in minor orders (such as deacons or acolytes) who committed serious crimes, such as rape, robbery, or murder, offences that would be punished in lay courts by execution or mutilation. However, these clerks were tried in church courts where they received much more lenient sentencing, ranging from penance, pilgrimage, to confinement. This was because the Church would not deform any man as he was made in the image of God.

Lord Williams examined the arguments on whether criminous clerks should be subject to universal civil identity. He questioned whether Becket was on the wrong side of Magna Carta and habeas corpus. Does restricting punishment only affect the criminals? Many would say it does not, as letting the guilty off lightly can destroy innocent lives. Yet Lord Williams argued that the legal wrangling on criminous clerks was not merely a binary struggle between the rational universal civil law and an alien body (the Church) that claimed special privileges. Indeed, he praised John Guy for rejecting the simple ‘textbook’ analysis of this confrontation; medieval law was a site of multiple contestations. Nevertheless, the Constitutions of Clarendon of 1164 sought to gain more authority for the king over the Church, by formulating articles on the customs of the realm. Clerks convicted of criminal activity should be handed to ecclesiastical courts and then handed back to lay courts. Yet was that not trying the man twice for the same crime? However, Lord Williams described the idea of ecclesiastical immunity, pursued by Becket and his coterie of lay clerics hot from the Schools of Paris, as ‘shaky ground.’ Codification of canon law and practice was important at this time, for Gratian’s Decretals and the investiture controversy had led to self-contained canon law, a system that did not work with ‘custom’. Anxiety by secular rulers remained concerning appeals over the head of the king. Therefore, the Church courts were perceived as a threat to sovereignty. The holding of land required swearing duty to an overlord, but what happened when it was churchmen swearing fealty to a lay lord – in disputes, should they appeal to Church law? Anselm, Alphege – and Becket – said they should.

In conclusion, the complex issues surrounding power and authority should not demote the ‘holy blisful martyr’ to a mere traitor to his prince. It was more, Lord Williams thought, that we can see the ambivalence used by Becket to consolidate resistance to his king. Henry’s bid for control was problematic but Becket’s response was difficult too – in ecclesiology resistance should use conversion not confrontation.

I hope you enjoy these reports and next week it will be Paul Bennett’s Becket Lecture and hopefully more news regarding the Tudors and Stuarts History Weekend 2021.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1882

1882

I read with some dismay the words “hopefully last online events the Centre will be running as we inch towards getting back to physical rather than virtual event” as while I totally physical events are preferable, making these events available online as well would be of great benefit to those people who for various reasons are unable to attend in person.

I “attended” the recent Pitt Rivers lecture at my former University (Bournemouth) recently and it was noted that there were more delegates viewing online than could have been accommodated in even the largest of the universities lecture theatres and there were delegates from as far afield as Argentina.

It was therefore decided that next year the lecture, as well as (hopefully) taking place with a live audience at the university, will also be made available to view live on Zoom. It would be great if, when normality returns and people can attend your events in person, they could remain available to view online for those people unable to be present in person.

Kind regards

Keith

Dear Keith

Thanks for your comment and I can understand your response, However, as you say yourself, physical events are preferable, and essential if it is a workshop which involves a much more interactive experience. One of the main issues involving keeping events as online as well as physical is the level of institutional support, which varies considerably. Thanks again, and I have noted your comments.

Best wishes

Sheila