As promised, I’ll come to the ‘Inspirational Kent Women Writers’ conference from last Saturday in a minute, but as a final reminder it will be the second part this coming Saturday when Dr Catriona Cooper will be leading the ‘Inspirational Women of Kent Co-creation Workshop’ at The Beaney. This too is FREE, and the workshop is a co-creative process where we’ll identify inspiring Kent women, collect information about them and write their biographies. The result will be a brand new interactive digital exhibition, mapping their lives and work, to share their stories and the places they happened.

As Dr Cooper say, “starting with Canterbury’s literary daughter, Aphra Behn, we want to share other women’s stories. Consequently, do you want to help spread the word about Kent’s Inspiring Women? Participants do not need digital skills, and support and refreshments will be provided.” So if this is for you, please do book at: https://ckhh.org.uk/events/details/inspirational-women-of-kent-co-creation-workshop

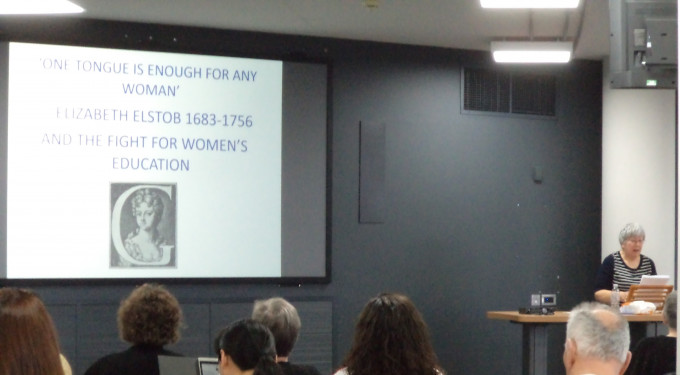

Now to the conference, by way of introduction, Dr Astrid Stilma drew attention to the idea that this event was a consequence of the AHRC-funded project on Aphra Behn involving the universities of Loughborough, Kent and Canterbury Christ Church and was taking place in Women’s History Month, thereby making it doubly appropriate and she welcomed everyone to the day and the first session, which was chaired by Councillor Connie Nolan who introduced her former colleague at CCCU, Professor Jackie Eales. The inspirational woman writer who was the subject of Jackie’s presentation was Elizabeth Elstob, a first-class Old English scholar who was passionate about the importance of education for women and a major supporter of women as writers. Born in Newcastle in 1683, her father died when she was five and her mother when she was eight, but even at this young age her mother had encouraged her education and she had already started to learn Latin before joining her aunt and uncle in Canterbury when she became an orphan. Not that her uncle Charles Elstob, a canon at the cathedral approved of such matters but her aunt was more sympathetic and ensured that she did have the opportunity to learn French. Moreover, the cathedral precincts may have been a good place for the young Elizabeth in that, as Jackie said, clergy households were more likely to have educated women compared to those of the laity being powerhouses of female education, albeit primarily in terms of biblical knowledge, spiritual commentaries and sermon notes.

Thus, she had a good start regarding her education, but things greatly improved when she joined her brother, first at Oxford and then in London, William having entered the church and become rector at St Swithin’s parish church. He, too, was a scholar and taking on the role as her tutor she learnt Old English, Latin and Greek, the siblings sharing a passion for such scholarship. William also introduced her to a group of like-minded scholars, including female intellectuals, who especially valued Old English texts. Such an interest might be seen as a revival of these works that had begun in Elizabeth I’s reign by men like Archbishop Parker and William Lambarde and continued under the Stuarts with Canterbury’s William Somner. For Elizabeth, her mentors and supporters included George Hickes, Dean of Worcester and Robert Harley, the First Earl of Oxford and Earl of Mortimer. Yet this time of opportunity did not last and the death of William in 1715 left her in a predicament and a couple of years later she seems to have fled to Evesham where she ran a small school. This difficult period came to an end when she became the governess of the Duchess of Portland’s children in 1738, and she remained in this post until her death in 1756.

She had the confidence to aim high concerning matters of patronage, dedicating both her translation of Madeleine de Scudery’s Essay upon Glory (1708) and an English-Saxon Homily on the Nativity of St Gregory (1709) to Queen Anne. Among her other publications, she used the method of collecting a formidable group of subscribers to help her publish Rudiments of Grammar for the English-Saxon Tongue and her facsimile of the Textus Roffensis is today in the British Library.

Thus she was recognised during her lifetime as one of a formidable band of female scholars in the early 18th century, and even though she might be said to have disappeared from (popular) view until the new wave of feminist studies in the 1960s, she is with others back again and Canterbury will in the near future be honouring both her and Astra Behn through the setting up of two blue plaques.

The next speaker on Saturday was Dr James Metcalf from the University of Manchester who took us into the world of Elizabeth Carter’s ‘church-yard’ poetry. Like Elstob, she was an accomplished linguist, and also like her she benefitted from being part of a clerical household, her father being perpetual curate at Deal. However, it was her poetry that James concentrated on, taking the audience through the complexities and emotions of her works through the linking of private piety and social activity through duty, as well as how she sought to contemplate, seeing the churchyard as the centre of rural society. Moreover, as he said, there are fascinating juxtapositions of the natural and the cultural in her work from the wood and the sun to the burial of bodies, set against ideas about organic decay.

Her letters are another source for scholars and provided her with a reflective space for her walks in the east Kent countryside around Deal, a marked contrast to her time in London or in the country houses of her various friends. Like others from this intellectual 18th-century world, she was interested in gardens as somewhat of a middle space between churchyard and salon, rural and urban, a place for self-cultivation and the linking of the past to the present.

This was a fascinating exploration of another ‘bluestocking’ and as well as her poetry she is perhaps best remembered for her works as a linguist, including an English translation of the known works of the Greek philosopher Epictetus.

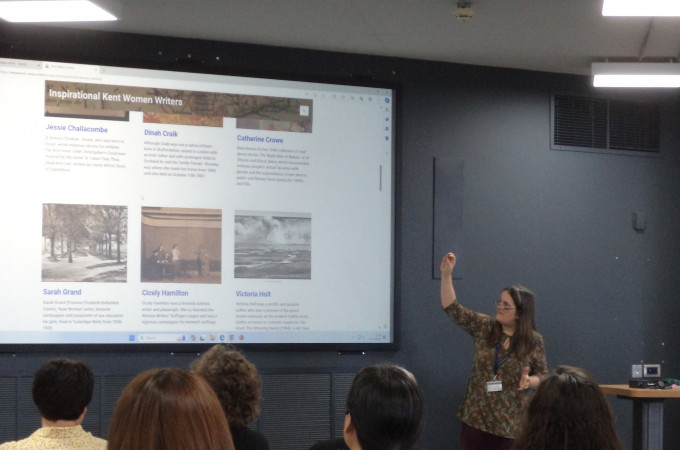

Then in the final session before lunch, Professor Carolyn Oulton and Michelle Crowther provided a preview of their exhibition on the papers and books in the ICVWW Special Collections exhibition on female writers (people visited over the lunch break), including Mary Braddon, amongst others, and Michelle showed us the range of Kentish women writers featuring on the Kent Maps Online website. One that especially interested me was Susie Colyer Nethersole for the late 19th century because of her use of Kentish dialect in her stories: https://www.kent-maps.online/20c/20c-nethersole-biography/

After lunch Dr David Shaw offered an interesting insight into the some of the people on the subscription list of Sarah Dixon’s Poems on Several Occasions (Canterbury, 1740). Dixon had been born in Rochester but spent much of her life in St Stephen’s Hackington just to the north-east of Canterbury and is buried there. Although the poems were written when she was a young woman, they were not published until much later and the 26 pages of subscribers include almost 500 names. As David said, this was one way of getting published as well as assuring the book of an audience, although why some people ‘bought’ multiple copies is less clear. The list offers information about social status, as well as the role of women as subscribers and matters such as occupation and geographical spread. This information and her biography itself, David feels would be a good topic for an MA by Research, there being material in Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library.

David was followed by Dr Laura Allen who provided an assessment of the life of Kent’s Bessie Marchant who lived in Petham and was the author of children’s fiction, drawing on her rural upbringing. Later her heroines were placed within the context of the Great War, their efforts contributing to the nation’s war effort. Laura is also interested in how we can recover the lives and works of such women writers through the archive, thinking about what, who and how such resources are curated, as well as ideas about girls’ fiction and how her voice can be heard.

Following what had been another very interesting session chaired by Dr Claire Bartram, we came to the final presentation of the day which was given by Professor Elaine Hobby. This was chaired by Councillor Charlotte Cornell and in a sense brought us round full circle because Elaine and Charlotte are heavily involved in the Aphra Behn project, and the subject of Elaine’s talk was Vita Sackville-West’s biography of her illustrious Kentish literary predecessor. Elaine provided a very useful handout including several quotations from Sackville-West’s biography, from Virginia Woolf and Aphra Behn herself, as well as details that Sackville-West had got wrong. Taking this as her backdrop Elaine explained that the biography emphasises that Aphra Behn had been able to earn her living as a writer. This sense of being on equal terms with men as a professional writer that comes through the biography, written by Sackville-West when Virginia Woolf was her lover and soon to publish A Room of One’s Own is valuable because it draws all three women together. For it highlights the idea that yes, Aphra Behn was exceptional as a prolific writer, and in order of importance playwright, novelist and poet, earning her living for 20 years, but she was not alone. The Civil War and the early Restoration period had provided the space for female published authors, including Quakers and Baptists thereby normalising the idea. Consequently, Elaine feels that modern critics have missed this when they discuss the ‘progress’ women have made in recent times and that the Victorian period has overshadowed how Behn and her contemporaries were seen and accepted as independent women who were ‘at home’ in the professional world of early modern England.

Like the other presentations, this generated several questions from members of the audience and in drawing the conference to a close, it was felt that this had been an extremely useful day with ideas that hopefully can feed into the workshop next Saturday.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2071

2071