I have been asked to pass on news of an archaeology lecture that is being given at Canterbury Christ Church on Thursday 19 October in Newton Nf03-04 at 5pm. It is entitled ‘Not Just the Bare Bones: Bioarchaeology of Roman Canterbury and the American Southwest’.

The lecture will be given by Lisa Duffy of the University of Nevada Las Vegas and her subject is the incorporation of a bioarchaeological perspective in the study of past human societies. This idea has emerged as a useful way to integrate archaeological data sets and create nuanced reconstructions of history and lifeways across time and space. Focusing on research from a late Roman cemetery in Canterbury and an Ancient Pueblo community in the American Southwest, she will discuss how contextualized analyses of human skeletal remains provide an opportunity to explore the various environmental, biological and cultural factors that have shaped the human experience as well as offer new avenues for multidisciplinary and collaborative research.

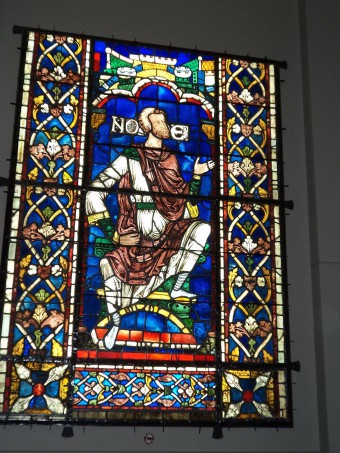

Noah – one of Christ’s Ancestors in the Chaper House exhibition.

This week I attended a meeting about the ‘Finding Eanswythe’ project that has recently received HLF funding and is being run by a team from Canterbury Christ Church, headed by Dr Lesley Hardy, and Canterbury Archaeological Trust [CAT] led by Dr Andrew Richardson, with others from several different organisations. Christ Church’s archaeologists are very much leading this but Dr Mike Bintley, an Old English literature specialist at CCCU, is also heavily involved because of his interest in Anglo-Saxon landscapes and the project’s focus on the miracle narratives associated with St Eanswythe. In addition to looking for archaeological evidence of the site of the Anglo-Saxon minster at Folkestone, that is the minster church and associated nunnery, the project will be looking at the water courses, natural and man-made that are seemingly linked to this Anglo-Saxon religious house. In addition, the team hopes to be able to reconstruct digitally what the landscape would have looked like in say the 7th century, and this will be one of the features on the project’s website.

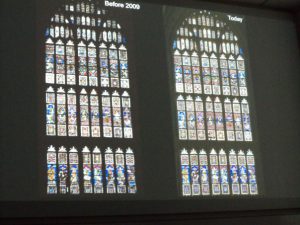

The Great South Window – before and after restoration.

On Tuesday, much of the time was spent going through the timetable covering the archaeological work which will include a whole range of non-invasive archaeological techniques, as well as some targeted excavations. These different phases will involve volunteers in addition to the professional archaeologists from CAT and CCCU. Although a little bit of this work has taken place already and a small amount more may happen before Christmas, most of the work will begin in 2018 once the new project co-ordinator is in post – interviews will be held fairly soon. All of this is very exciting for a whole range of different reasons and it will be fascinating to see how this project develops and what the team is able to find out about this important part of Folkestone’s history, and one mostly lost under the modern housing developments and other buildings associated with the town’s recent history following the coming of the railway in the 19th century.

Keeping with what may be called the Middle Ages, this week I also attended a lecture given by Leonie Seliger who is the leader of the team of stained glass specialists at Canterbury Cathedral. This talk was organised by the Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society [CHAS] and took place at Christ Church. A packed lecture theatre was delighted to welcome Leonie for what is called the William Urry Memorial Lecture, an annual talk that remembers the contribution William Urry provided for Canterbury both as the cathedral archivist and as the author of Canterbury under the Angevin Kings and other articles about Canterbury’s past, especially its medieval history.

‘Enthusiastic’ destruction in the 17th century.

Leonie took as her subject the tale of the restoration of the great south window in Canterbury Cathedral that began almost a decade ago in 2009 when a large piece of masonry fell from one of the principal mullions of the window. For when the structural engineers went up to look at the stonework immediately after this unfortunate incident they found the damage was far worse than they had imagined with splits in the stonework everywhere both on the inside of the window as well as the outside. Thus, began a very major project and one that the Dean & Chapter had not envisaged and therefore certainly hadn’t planned for! Because it became clear that the whole window would have to be restored, with large amounts of the stone actually replaced with newly carved French limestone blocks, albeit as much as possible would be saved, and, in the end, this amounted to about 50% of the tracery.

Of course, to do such a major project on an ancient monument and part of a World Heritage Site required permissions from a wide variety of bodies and this took about two years. Moreover, such an undertaking required the work of the cathedral’s expanded masonry team as well as Leonie’s team of glaziers because rebuilding the window required the removal of the precious medieval stained glass, although the protective glazing, put up in 1970, remained in place. Yet in some ways for Leonie, as well as being a very major challenge, the project did open up amazing possibilities to look again at the history of the window; to introduce people to Christ’s ‘Ancestors’ close-up and personal; to examine this fantastic set of medieval panels from a glazier’s perspective using new scientific techniques; to put right some of the interventions done on the window over the centuries, particularly those relating to ventilation of the glass; and to gain an understanding of how the window might have ‘worked’ when it was originally constructed – the interplay between glass and stone where each enhanced the other as medieval theologians such as Abbot Suger understood and which would be employed in some of the greatest medieval cathedrals in France, as in England.

Evidence to suggest archiepiscopal patronage of the great South Window.

To return to what was in the window by way of stained glass, due to iconoclastic destruction in the 16th and 17th centuries, in 1660 a great deal of plain glass was fitted in large parts of the cathedral. Just over a century later in the 1790s, those in charge decided on an ambitious plan to reglaze the great south window by moving panels around within the cathedral. There were three targets which seemed to fit the bill: the great Ancestor windows from the clerestory, albeit some of these were no longer the originals, especially on the south side due to erosion and other damage over the centuries. The second target was heraldic glass from the nave and the third were borders and other assorted medieval glass dating from the 12th to 15th centuries from elsewhere in the cathedral. What, of course, had been there originally remains a moot point, but using ideas about the similarity of the west window, Leonie thinks there is a good chance the first patrons of the glazing scheme were archiepiscopal.

Skipping over much of Leonie’s fascinating talk, she and her team looked at comparable work that had taken place at York Minster regarding issues such as ventilation of the window and concerns relating to how do you store 179 precious beyond measure medieval stained-glass panels. However, perhaps of even greater interest to the audience was the work Leonie had undertaken with the Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum in New York regarding exhibiting six of the Ancestor figures. Furthermore, the exhibition in Los Angeles also involved folios from the St Alban’s Psalter, a wonderful bringing together of stained glass and illuminated manuscript. These exhibitions were extremely nerve-wracking – just the detailed requirement regarding shipping and that Los Angeles is in an earthquake zone were enough to give Leonie sleepless nights, but all went well and the number of visitors was staggering. Not to be outdone, the Chapter House at Canterbury Cathedral was similarly converted to an awe-inspiring exhibition space and, of course, all the Ancestors were at Canterbury. Having attended the purpose-built exhibition, including a talk by Leonie where she discussed such matters as how Jews were depicted, the techniques used by the Methuselah master and other fascinating topics, I can vouch for the magnificence of the display in the Chapter House.

Leonie showing the effect of light through the ‘new’ border glass.

Finally, there was the matter of putting the panels back in the ‘new’ window, an amazing feat and the result that can now be appreciated because all the scaffolding has now been removed. Yet before I finish, I just want to comment on what Leonie said about a small piece of replica border glass that her team constructed to see the difference between it and the corroded glass. Leonie’s team created it just as it would have been done in the Middle Ages using early techniques and tools. Now, as she said, it did look new, perhaps in some ways ‘flat’ but the real revelation was just how much light it let through compared to the corroded glass – turning it almost into a spotlight.

When she finished, the audience gave a rapturous round of applause and after answering several questions for eager listeners, the lecture was drawn to a close with a vote of thanks and another great round of applause. If this sounds interesting, Leonie will be giving the opening lecture on the Friday evening of the Medieval Canterbury Weekend, and I’m sure she will be as equally well received there as she was this week. For details of the Weekend, please do consult the website at: www.canterbury.ac.uk/medieval-canterbury or email artsandculture@canterbury.ac.uk or phone 01227 782994.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1210

1210

Hello. I’m a temporary member of staff and I’d be interested to find out more about Finding Eanswythe. I previously volunteered in Brighton Museum (when I studied at University of Brighton) and my research area is around community art and digital spaces. I’d really like to get involved with the digital reconstruction. In my volunteer role, my team commissioned a Minecraft map for a Stone Age session.

Hello, good to hear that you are interested in the project. I would suggest that you contact Dr Lesley Hardy who is in the School of Humanities. I am sure she would be delighted to speak to you.

Best wishes, Sheila