Even though it is a couple of weeks away, I thought I would draw your attention to the Centre’s next joint evening lecture with the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust (FCAT) on Thursday 16 November at 7.00pm in Newton, Ng07 when Clive Bowley, who was for a long time Canterbury City Council’s conservation officer, will be discussing a selection of Canterbury’s many timber-framed buildings. I am sure this will be a fascinating talk, so do please come along if this interests you.

This week has brought a feast of lectures about Canterbury’s history and its place within the wider world at two crucial periods in its and England’s history: the Norman Conquest and the Reformation. Even though I will focus exclusively on the former because of the Canterbury Christ Church connection, as the audience discovered on Thursday, Dr Stuart Palmer and Dr Silke Muylaert’s discoveries concerning the impact of the Reformation and its consequences in the city are fascinating, whether we are considering the activities of the most successful printer outside London in the 1530s and 1540s or the role of the Walloon Church in Canterbury and beyond.

Late Anglo-Saxon portable sundial, previously displayed in the Canterbury Heritage Museum.

To turn to the event last night, as one of the students who benefitted from Professor Alfred Smyth’s lectures and seminars on ‘Medieval Christendom’ in the late 1980s, it was great to be part of the large audience (comprising his former colleagues from Kent and Canterbury Christ Church, former and current students, his family, friends and neighbours, and members of the public) that trooped into the Grimond lecture theatre at the University of Kent to honour his memory. As Richard Eales recounted in his introduction, he and Alf Smyth had lectured at Kent for several decades in the late 20th century, Alf having arrived at the university by way of Dublin, Oxford and a short spell of teaching at the University of Birmingham. Moreover, Alf Smyth had not only taught early medieval history, especially ‘The Dark Ages’ at Kent, but had been master of Keynes College for part of his time at the university and had instituted ‘The Dark Age Lecture’ that brought a whole host of well-known historians down to Canterbury.

During his time at UKC, as it was then known, he was a prolific writer and his many books included works on medieval Scotland, the ‘Viking’ settlements in Ireland and Alfred the Great. He was still publishing when he left Kent to manage St George’s House at Windsor Castle, and when he returned to Canterbury at the end of the 1990s to become Director of Research, Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and a Pro Vice-Chancellor at what was then Canterbury Christ Church College. Retiring in 2005, he remained actively engaged in the study of history, including exploring more locally in east Kent almost up until his death in October 2016.

Paul Bennett in a deep excavation of the bailey ditch.

To a degree taking this as his cue and Alf’s expertise on Anglo-Saxon England, Richard introduced the speaker for the evening. I have reported on Tim Tatton-Brown before when he came to Canterbury to give a lecture, in conjunction with the Centre, at Canterbury Christ Church as part of the 40th anniversary celebrations of Canterbury Archaeological Trust, but for those who haven’t seen this blog I’ll say a little about Tim before getting to his lecture. As Tim said, he arrived in Canterbury in 1975 as a Roman archaeology specialist but immediately found himself having to organise archaeological excavations in the city and surrounding areas that were largely investigating the post-Roman world. Among the people he talked to and gained much from were Alfred Smyth, Nicholas Brooks and Stuart Rigold, all experts in different aspects of Canterbury’s history either side of the Norman Conquest. The late 1970s and early 1980s were exciting times for Canterbury archaeology and, as well as Tim, Paul Bennett was deeply involved in many of these excavations – note the depth of the hole! Among the sites Paul worked on were those linked to the Norman castles, i.e. both the first and second, and it is worth noting that there have been and will be more exciting discoveries regarding the first – the motte and bailey castle, as the Trust continues its excavations between Canterbury Police Station and the road to Canterbury East station.

Tim showing Archbishop Anselm’s seal on the ‘new castle’ charter.

However, to return to Tim’s talk last night, he took as his subject ‘Canterbury in Domesday Book’. He pointed out to the audience that the paragraphs about Canterbury in Domesday are very oddly arranged. They begin on page 2 but after an initial paragraph the scribe then moved to consider Dover and then the principal landowners in Kent. Yet what Tim wanted to draw attention to is the entry about the main (straight) roads out of the city where the king was to have any fines for misdemeanours committed up to a distance of 1 league, 3 perches and 3 feet. As he said, this distance corresponds closely to the city boundary beyond the walls regarding the roads to Dover and Sandwich, but he said the Trust had not found the Roman road that links to Roman Stone Street which goes due south towards Lympne (Stutfall Castle). Nevertheless, if you look at the footpaths between the city walls and Stone Street (and Iffin Lane) there would seem to be a prime candidate for the line of this road that comes over the hill from Stuppington and conceivably joins Lime Kiln Road (and then not only passes Martyrs Field but also seems to pick up the ward boundary between Worthgate and Ridingate (from the city’s 1790s map). To the west of the city in a large arc beyond the wall it was the archbishop not the king who collected the fines because the land on either side of the ‘straight’ road belonged to the archbishop. This main road leading out of the Westgate heading towards Seasalter (and London) was within the great archiepiscopal hundred and manor of Westgate, an extremely large area that extended beyond the Blean forest to the coast.

So much for the land holding and road system beyond the surviving Roman city walls, because Tim then turned his attention to other markers of late Anglo-Saxon Canterbury such as finds like a portable sundial found in the cathedral precincts, an early 10th century knife, the quoins at the south-west corner of St Mildred’s church of probably a similar date, the dedication of St Alphage church in the archbishop’s part of the city, the nave of the Anglo-Saxon cathedral uncovered by the Trust when the Dean and Chapter were repaving the nave, much earlier excavations at St Augustine’s Abbey that discovered the massive rotunda as part of the great abbey church, the system of chapels at or above the city gates, and the continuing use of St Martin’s church for Christian worship that predates 597 and was mentioned by Bede.

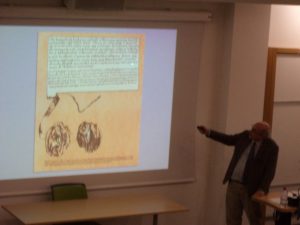

Transcription and drawing of Bishop Odo’s seal, by Christopher Hatton, original charter lost in the Cotton Library fire.

Having set the scene in pre-Conquest Canterbury, Tim then considered what we know about the arrival of William and his army, subsequent royal building projects including the two castles, the equally important major works undertaken by Archbishop Lanfranc and his successor, and the effect Bishop Odo had on land holding and use at Canterbury beyond the walls. Consequently, Tim discussed William’s early motte and bailey castle, including recent excavations that have now conclusively shown this not only had a great bailey within the city walls but perhaps an even larger one beyond the wall. This royal presence would become the Donjon manor of which a tiny fragment survives in terms of doorway but little else. He also pointed out that soon after, around 1100, a second royal castle was constructed by William II, as mentioned in Archbishop Anselm’s charter, and still survives in part albeit it has and continues to suffer seriously from neglect. Anselm himself was also building and following on from Lanfranc today we have the fabulous cathedral crypt that he masterminded, an area that featured in the blog a few weeks ago.

Bishop Odo was also busy, one of his major acts being to carve a rather nice hunting park called Trenley Park out of the eastern Canterbury archiepiscopal lands (Colton and Caldecote manors or Little Borough) which became a detached part of Wickhambreaux. Even though Odo’s success was short lived, rebelling against the king was rarely a good idea, the park as an area survived. Notwithstanding such ‘encroachments’ the archiepiscopal lands were extremely extensive even after Lanfranc had subdivided the cathedral lands so that the monastery had its own estates such as the manor of Barton. St Augustine’s too continued to be a major land holder in and around Canterbury with its manor of Longport.

Part of Archbishop Lanfranc’s palace complex.

Nevertheless, longer term it is perhaps Archbishop Lanfranc’s great building projects that were really the most noticeable change to the Canterbury landscape. For not only did he knock down and replace the Anglo-Saxon nave of his cathedral following the fire there, as well as enlarging the dormitory so that it could accommodate up to 150 monks, but he was prepared to alter the road layout, which included the destruction of 27 dwellings (reported in Domesday) so ensure he could have a massive palace. Part of the shell of this complex was uncovered during Tim’s time as the Trust’s first director, thereby providing an idea of just how extensive it had been as well as ideas about expensive. In some ways equally lavish were the two hospitals created by Lanfranc at Harbledown and Northgate, the latter dedicated to St John being especially so with its massive dormitory block using Caen stone, its two lavatory blocks, the kitchen range and the double chapel.

Tim also discussed the activities of the great ecclesiastical landholders in east Kent either side of the Conquest, but I think I will stop here and just conclude by saying that the audience was exceedingly appreciative of Tim’s lecture from the level of applause he received. Furthermore, he was happy to answer several questions before Paul Bennett came forward to give a vote of thanks for such a stimulating and entertaining talk, as well as thanking the university of hosting the occasion. Indeed, I think Alf Smyth would have been delighted with Tim’s lecture, and I’m sure Alf’s wife Margaret and their two children were exceeding pleased on his behalf because it is rare to see a large lecture theatre so packed for an evening lecture!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1939

1939