Before I get to the Lunch Time Lectures – today and next week, I thought I would bring you some exciting news about the Becket 2020 online conference, the Manorial Register for Kent, and the CHAS online conference coming up shortly, as well as just briefly mentioning that there is now a small group working on medieval and early modern wills for Newenden and surrounding parishes as part of the Lossenham project. We had our first online meeting this week and everyone is enthusiastic with work having already started and we are now going up a gear – more on this in future weeks and thanks to everyone involved.

CCCU through the Centre is involved in the revamped Thomas Becket: Life, Death and Legacy conference which will take place online between 28th and 30th April. This collaborative event organised by the Heritage Lottery funded project ‘The Canterbury Journey’ at Canterbury Cathedral, the University of Kent and CCCU will bring a host of exciting ‘live’ speakers including keynote lectures by Dr Rachel Koopmans and Dr Paul Webster. As well as these ‘live’ talks over three days, there will be several pre-recorded presentations to give a flavour of Becket and Canterbury to the proceedings, a sense, the organisers hope, of ‘being there’ in this world of virtual events. Moreover, this will mark the beginning of the British Museum’s exhibition on Becket 2020 that will feature some of the stunning stained glass from the Becket windows. Indeed, Rachel will be revealing at the conference several great discoveries she has been making with Leonie Seliger from the Stained Glass Conservation team at Canterbury. For more details, please go to: https://becket2020.com

Some regular readers of the blog may remember that we at the Centre last March were in the process of organising a workshop at CCCU with the Kent History and Library Centre on the Kent Manorial Register to showcase it as a new, terrific resource for researchers. However, like so much else the workshop fell victim to COVID-19 and the pandemic similarly slowed the final stages of getting the Kent Manorial Register up online. However, the wait is now over, and the Kent section of the national register has now been launched. Please do have a look because this is a very exciting development, much of the work having been done by Elizabeth Finn at KHLC: https://www.kentarchives.org.uk/manorial-document-record-project/. Once things improve and indoor socially distanced events can be held again, we will revitalise the idea of holding this joint workshop with KHLC.

Returning to an online event, the Centre with the Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society will be holding a half-day ‘Canterbury through the Centuries’ conference on Teams Live Events on Saturday 13 February. The conference will start at 10.00 (log in a few minutes beforehand) and will feature four speakers exploring important dates ending in ‘20 to mark the Society’s centenary last year. I’ll add the joining url to the blog next week, so watch out for that and the four speakers on the 13 February will be me (1320 and 1420), Dr Stuart Palmer (1520), Dr Lorraine Flisher (1620) and Dr David Budgen (1920).

The conference is free and if you enjoy it and aren’t a member of CHAS, please do think about checking out the Society’s great website and joining. CHAS always has a great selection of monthly winter lectures, the February 2021 one will be given by Dr Claire Bartram, the Centre’s Co-Director on early modern literary representations of Dover. These are fascinating, and some are quite unexpected.

Returning to the Lunch Time Lectures, firstly, for next week at 1pm on Wednesday it will be Jacqueline Stamp. She will be discussing representations of the Arctic in nineteenth-century literature, the subject of her doctoral research at CCCU in English Literature, and it sounds as though we are going to be in for another treat. If you want to find out more beforehand, please look at: www.c19arcticrepresentations.wordpress.com

As before these are free to attend online and join about 5 to 10 minutes before start time – see joining url below: to join Teams (as you would for Zoom) click on the link or paste in your web browser. Then on the screen click on ‘Open Microsoft Teams’ (centre, top in the little panel, not the buttons in the middle of the screen). Then to get you into the lecture as an attendee click ‘Join now’ (as you would for Zoom). If you have any problems, please contact the CCCU IT Helpdesk on 01227 922626 or email: it-service@canterbury.ac.uk (weekday office hours only).

So to today’s Lunch Time Lecture which was given by Cassandra Harrington (University of Kent) who is in the final stages of writing up her doctoral thesis – due to be submitted at the end of March. As an art historian, Cassie is interested in marginal sculpture, manuscripts and illumination, architecture, and the dialogue between visual and textual modes in medieval Europe. Her chosen period covers c.1200 to c. 1350 and is labelled Gothic by scholars, which means she investigates such architectural gems as the cathedral at Chartres, the buildings of Cluny, and on this side of the Channel amongst others the cathedrals at Canterbury, Lincoln and Norwich.

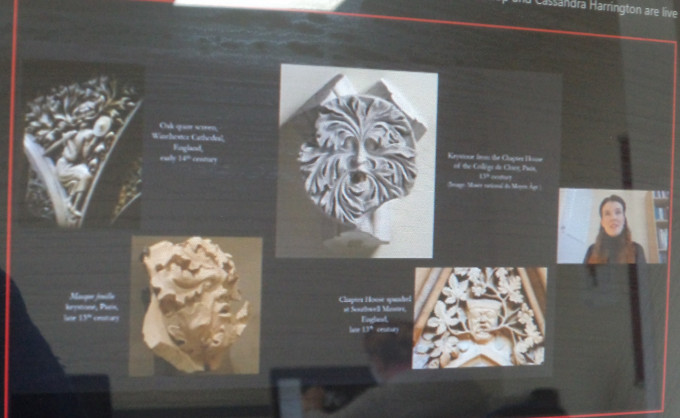

She began by pointing out that foliate faces have a long history, from a few first century Roman examples to their ubiquitous presence in the twelfth century across western Christendom and with a few examples in the eastern Mediterranean. From her studies, she has found that broadly the foliate mask is far more common in France, while English examples from this period are far more likely to be disgorging foliage. Moreover, she was keen to emphasise that these were not solely decorative pieces but need to be understood in terms of language. For their linguistic value was understood by contemporaries allegorically, thereby offering moral, spiritual and theological ideas to be read whether such foliate figures were in stone, wood or in the margins of manuscripts.

Nevertheless, these foliate figures have primarily been the domain of folklorist in more modern works, especially following the intervention of Lady Raglan in her published article in 1939 where she referred to such a figure as a ‘Green Man’. This has brought links to ideas regarding them as symbols of fertility and rebirth. However, as Cassie said they aren’t green and they aren’t only men because there are examples of women, animas and grotesques. So if we discount the use of this modern name, what did medieval people call them, and as Cassie said from a thirteenth-century manuscript by Villard de Honnecourt we see the term ‘head of leaves’, hence the term used by scholars of the foliate head.

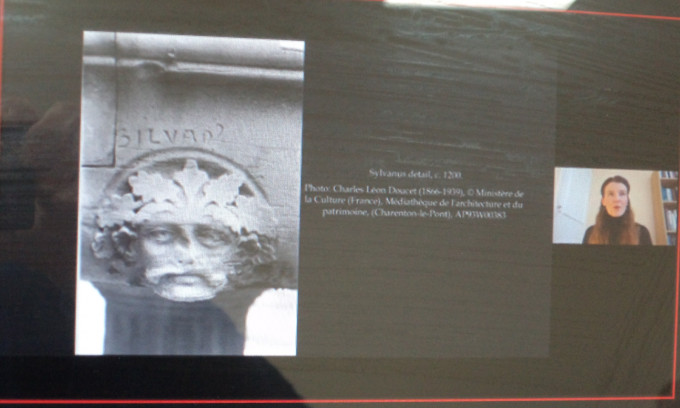

Having provided this background, Cassie turned to two case studies in her thesis. The first is an early example within her time period, a foliate head sculpture on a two-tiered fountain at the basilica of Saint-Denis, the great former abbey church in northern Paris. This Benedictine monastery built on the site of a Gallo-Roman cemetery became the burial place of French kings from the tenth century onwards. It was much rebuilt in the new Gothic style by Abbot Suger in the twelfth century, with further work in the early part of the next century that included the cloister and the fountain. Over the centuries the fountain was moved and suffered significant erosion from pollution which means much of the inscription has been lost. Consequently, Cassie is heavily reliant on later drawings, but these are extremely helpful. First, they show that the fountain could have been used by the monks on all sides which means that it was presumably positioned in the centre of the cloister. Moreover, it is possible to reconstruct the arrangement of the 28 heads – each carved in profile and as portraits, and to see that they represent classical figures such as Greek and Roman deities, virtues and others including Paris and Helen, Dives and Pauper, and Flora and Faunus. Thus, this cohesive programme was designed to work as pairs or as larger groups, and amongst them is Silvanus as a foliate mask. The monks aware of this arrangement as they performed their ablutions before entering the abbey church.

As Cassie said, sixteenth-century scholars believed this was of Roman origin because stylistically the idea of the carved head with an inscription above bears considerable resemblance to the pillar of boatmen, also in Paris and dating to the first century. Moreover, the way the foliage was portrayed was also seen to indicate such borrowing of ideas. And not just in terms of the physical carving, but also from the word of ideas based around the sense of transformation found especially in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Now such classical literature had been assimilated into medieval Christian teaching with these texts equally valued for their instruction in grammar and in allegory. Consequently, such sculpture was good to think with, to meditate on to find God’s hidden truths.

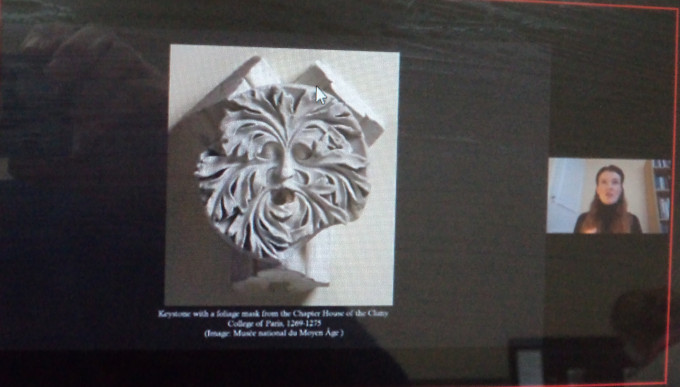

Turning briefly to Cassie’s second case study, this concerns the roof boss from the chapter house of the Cluny College of Paris. Interestingly, the chapter house was beyond the west end of the church and to the south of the chapter house was the refectory, there being entrances to both the church and refectory from the chapter house. This keystone with its foliate mask is no longer in situ but from its Y-shape Cassie has deduced that it was in line with the doorway from the chapter house to the church, that is halfway to the central boss. Thus, as the monks processed from the church, they would have come eye to eye with what would have been a brightly coloured face with its mass of foliage.

Thinking again about influences, Cassie drew her audience’s attention to the importance of Charlemagne as a patron of art and learning from the ninth century. For through the networks of scholars he introduced to his court, he had been able to cultivate a community interested in classical scholarship, seeing it as a means to enhance and develop Christian doctrinal ideas. As you would expect allegory was a central pillar, and for the deployment of ideas linked to foliate heads the multiple meanings attached to the notion of branches is especially pertinent.

Cassie concluded by showing her forty or so audience members a range of foliate heads from beyond France, looking as far east as Greece and west to several from Britain, with her final slide being the foliate head from Canterbury Cathedral. Thus, ended a fascinating lecture that sparked a range of questions, as well as the comment from one questioner that they are looking forward to the publication that will come from this thesis.

We are the Centre would, therefore, like to thank Cassie for her beautifully illustrated and interesting lecture and wish her all the best for the final stage of her thesis. Moreover, I would like to thank Dr Diane Heath once again for acting as the producer, and equally I am very grateful to Toby Charlton-Taylor for providing IT back up. We hope you will join us next week when we head north to the Arctic.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1444

1444