Firstly some news about what will be taking place next week. Next Tuesday Abby Armstrong, who successfully defended her doctoral thesis just before Christmas, will be giving a paper on the daughters of Henry III, the first in the History seminar series at CCCU for this term. I expect to see lots of staff and postgraduates there, and if this sounds interesting, please do come along and join us in Newton, Ng01 at 5pm. Then two days later, the Centre with the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust [FCAT] will be holding their January lecture in Newton, Ng07 at 7pm, when Dr Steve Willis (University of Kent) will speak on ‘Roman Lympne: context, new research and new questions’. Again, all welcome and we would be delighted to see you.

Today I want to bring you a short report on the Canterbury Historical Association’s January lecture because it was an excellent presentation and secondly because it was chaired by Professor Louise Wilkinson, one of the Centre’s directors and a member of the local HA committee. The lecture was hosted by Cressida Williams and her team at Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, and the packed reading room was treated to a fascinating analysis by Professor Katy Cubitt (University of East Anglia) of concerns about the Apocalypse and how much they coloured ideas at King Æthelred’s court, especially in Anglo-Saxon England around the year 1000. This is an area of research she has been working on for several years, consequently it was great to hear her assessment of Archbishop Wulfstan of York’s sermons which draw on such notions as the ‘Endtime’ from the gospels (see Matthew 24. 7-9; 24. 12) and the Book of Revelation.

Louise Wilkinson introduces Katy Cubitt [sorry Louise – you moved at the ‘wrong time’]

She began with Wulfstan’s ‘Sermon of the Wolf to the English’ which includes ‘… this world is in haste and the end approaches; and therefore in the world things go from bad to worse, and so it must of necessity deteriorate greatly on account of the people’s sins before the coming of Antichrist …’, which she sees as significant because of his stress on the sinful nature of the Anglo-Saxons. However, before looking at this and a couple of his other sermons in more detail, she provided a contextual overview of ideas in mainland Europe, as well as what was happening in England. For, as she said, scholars working on continental 10th-century sources believe there was a strong feeling, with a popular dimension, that the millennium did indeed mark the beginning of the end. Even though the actual number of texts espousing such views is tiny, yet it does seem those in power, including Otto III, were able to tap into such deep concerns.

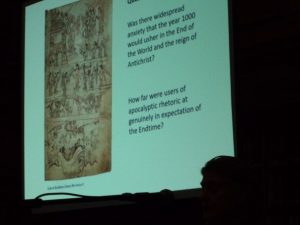

In contrast, scholars studying late Anglo-Saxon England have generally not followed this line, seeing instead the Viking raids and later invasions as the primary preoccupation of the English, that is solely in earthly terms. However in the 2010s, there has been a growing appreciation among academics that fear of the impending Apocalyptic may have had a place in Anglo-Saxon thought, although whether that is because it was truly believed or more because of its use as a rhetorical device was one of the questions Professor Cubitt posed. Certainly, things were not going well for the English, Viking attacks in the 980s had escalated in the following decade and the catastrophic defeat of the Battle of Maldon (991) seems, as Katy said, to have ushered in a period of penitential kingship by Æthledred. For example, he issued several charters over the next decade to expiate the sins of family members by making good earlier land grants to religious houses that hadn’t actually been fulfilled, in order to seek to safeguard their souls and his own.

Note the rather splendid Hell mouth at the bottom of the illustration

Yet things in England did not improve, the dreadful famine of 1005 merely putting off the Viking armies for a year as they attacked mainland Europe instead before coming back to England the following year. For Canterbury, of course, the year 1011 was catastrophic, the 3-week siege and subsequent destruction a startling reminder of Viking power. In 1014 Æthelred fled, the kingdom in the hands of Swein Folkbeard until his death, before passing to Cnut in 1016 on the death of Æthelred.

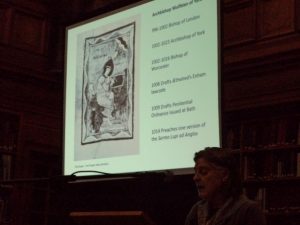

Returning to Archbishop Wulfstan’s sermons, Professor Cubitt noted that within the almost 50 sermons of his that we have there are these 5, dated c.1006–1012, that employ Apocalyptic ideas in various forms. Such a 6-year period, she believes, shows that they should not be seen as simply from one phase of his life, especially because he used these sermons over an extended period. For example, there are 3 versions of the Wolf sermon in 5 manuscripts, he is known to have preached it in 1014 and on other occasions, and we know that he drew on current examples to give greater impact for his probably courtly audience. Thus Katy sees Wulfstan developing and exploring ideas, as well as responding to events, which meant he drew on themes such as the time of the Antichrist had yet to come, but that because it might be imminent – one never knew, nor should one speculate following Augustinian thought as Church orthodoxy – the English should be ready at all times by turning away from sin, and that they should be helped by churchmen to do so. To drive home such points, he provided a catalogue of their sins, and highlighted that just as God had punished the sinful British by aiding the Anglo-Saxons, now the Vikings were similarly God’s weapon, alongside famine, against the sinful English.

Professor Cubitt discusses events around 1000

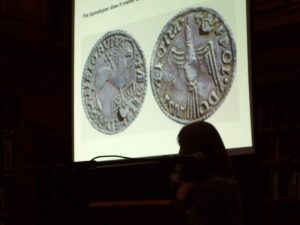

In terms of the dissemination of such ideas beyond the court, she believes this was achieved through the issuing of law codes, probably written by Wulfstan for the king, which would have been propagated through the shire and hundredal systems in place across England, as well as a 3-day national penitential scheme of fasting and pilgrimage in 1009, including the issue of an Agnus Dei penny. Yet, it is interesting to speculate just how far peasants and townsmen generally would have equated these disasters in Apocalyptic terms, even though the idea of God’s wrath might have had credence. Professor Cubitt is still exploring such ideas, and she left her audience with 3 thoughts to take way: was there a popular anxiety? Are we looking at an apocalyptic mentality within religious and political thought? And what else was going on, that is the need to really understand the context if we are going to gain ideas about this past age.

The Agnus Dei penny – note also the reference to Alpha and Omega

The applause was long, and her appreciative audience was delighted to be invited to ask questions. Katy fielded several of these, including one on Wulstan’s response to Archbishop Ælfheah’s murder at Easter 1012. She said she thought Ælfheah, although a Benedictine like Wulfstan and keen to support the contemporary reform movement instigated by that order, was in other ways very different. She feels he had a special interest in the lives of saints and may have been looking for martyrdom, and, if so, there may be more similarities to Becket than previously thought. However, she did acknowledge we know little about him, and she will give this relationship between the two archbishops further thought.

Just as a final point for this week, I thought I would mention that CCCU had its winter graduation ceremonies in Canterbury Cathedral yesterday. Among those receiving her doctorate was Harriet Kersey, and regular readers of the blog will have heard about Harriet before, whether it is her doctoral studies on aristocratic women in 13th-century England or her work on the ‘Medieval Faversham’ exhibition, which I believe is still on display in 12 Market Place, Faversham. Thus, many congratulations Harriet!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1659

1659