Being busy trying to edit the last in the Kent History Project series: Early Medieval Kent, 800–1220, which needs to be finished and off to the publisher by the 1 September this year, I was grateful to a friend who suggested taking a few hours off to watch a cricket match. As a result we watched Kent comfortably beat Hampshire in a 50-overs a side match, although it had looked less comfortable during Hampshire’s opening stand and Kent’s minor batting collapse. It was a very pleasant atmosphere, and walking through the redesigned entrance to accommodate the housing and retail developments that have been built in recent year, it made me think of my research report for Canterbury Archaeological Trust regarding the ‘Bat and Ball’ site as it is designated. Thus as a way of providing something this week, I thought I would draw on a couple of aspects of the site’s history but not the medieval leper hospital, rather the Tudor/Jacobean mansion house that followed it, as happened to so many of Canterbury’s religious houses (and similarly nationwide), and then just a couple of what I think are interesting points about the early cricket ground.

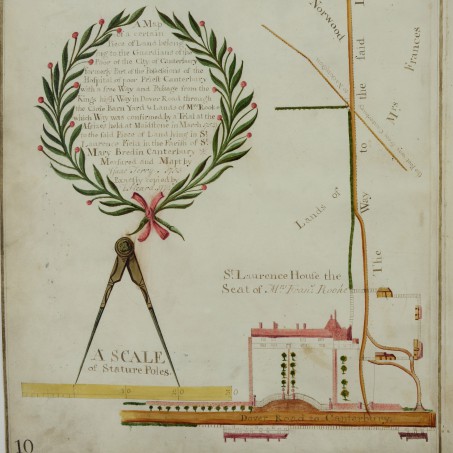

Poor Priests’ map showing St Lawrence house

copyright: Canterbury Cathedral Archives & Library

The ‘death’ of St Lawrence’s hospital was a protracted affair, beginning in 1538 when the hospital site was leased for ninety-nine years to Sir Christopher Hales of Hackington, who may have rented it out to a Canterbury yeoman because Dedyer Tompson styled himself ‘of St Laurence beside Canterbury’ in 1545. At this time a few of the sisters were still there and they were allowed to remain as part of the terms of the agreement, and, indeed, some managed to survive into Elizabeth’s reign, the last having gone or died at some point in the 1560s. Even with the sisters the property attracted considerable interest and there were a number of disputes over who held it in the late 16th century because not only did it comprised a substantial mansion house and subsidiary buildings (barns, stables, a dovehouse, other buildings, orchards and gardens) by this time but the holder also had the St Lawrence Tithery. Being a tithe collector offered rich pickings, especially as the farm land in these Canterbury suburbs was being turned over to the new hop gardens at a time when the demand for beer, and thus hops, was on the increase.

By early in James I’s reign the St Lawrence estate was in the hands of Richard Best, albeit on a lease from the Crown. However we get a really good idea of the estate not from the royal records but from Richard’s probate documents. In 1633 he bequeathed his goods, lands and tenements to his son John, but it is his inventory where we get a far better idea of what this meant regarding the mansion house. Consequently, even though the appraisers may not have mentioned all the rooms in the house, they did list a hall, parlour, study, kitchen, buttery, bakehouse, chamber over the kitchen, a gallery over the parlour, a chamber over the hall, a chamber over the study, a garret over the hall, a barn and podder house. Presumably within the main house on the ground floor were the hall, parlour, study and kitchen, the latter presumably no longer detached, yet still forming a group with the buttery and bakehouse. There were fireplaces in the parlour and study but there is no mention of utensils for fire making in the hall (but there was an iron cradle?). Instead the hall had a plain table and forms, playing tables, a clock and a considerable amount of glassware, perhaps for dining or entertaining. The parlour also seems to have been used for recreation because there was a pair of virginals and six green cushion stools among other things. The study was not just used for the keeping of books, having as well 128 pieces of pewter, much of it old and battered, and a set of scales with weights. The kitchen was well stocked with cooking equipment and utensils, and the buttery and bakehouse were similarly well supplied. The household apparently slept on the first floor. The chamber over the kitchen, that over the study and the gallery over the parlour each had a bedstead and its furniture varying in value between £3 10s and £6 13s 4d. In addition, there were two trundle beds and a servant’s bed in the garret over the hall, but none at all in the chamber over the hall. Several rooms had chests, cupboards and presses, yet only the chamber over the study contained any fire-making equipment. Nevertheless, there would appear to have been enough hearths for the house to have had a forest of chimneys, presumably elegant brick ones that you can still see on late 16th- and 17th-century houses, and can sort-of be seen on the later maps of the St Lawrence estate. There are a number of these in the St Lawrence Tithery collection at the Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, as well as a map of the late Poor Priests’ hospital estate (see above) that came into the hands of the city corporation in Elizabeth’s reign.

Just as a footnote, John Best did not keep the estate, selling it together with the Tithery of St Lawrence to William Rooke, esquire, for £2080. I am going to skip the Rooke family’s residence at St Lawrence and pick up the story again around 1800 when the old mansion house was in a bad state of repair. At some point in the first decade of the 19th century a new house called Nackington House was built and St Lawrence House (except the more modern kitchen apartments) was pulled down and the site grassed over. According to the 1839-tithe map, the field between the house and the Old Dover Road is labelled pasture and that between this field and the junction with Nackington Road is described as arable. Behind the house and 2-acre garden is a 16-acre block of parkland, its southern and eastern boundaries being that of the later cricket field. By the time the tithe map was drawn, the property was owned by Lord Sondes (whose landholdings locally included the Nackington estate) and was occupied by George Mount as part of Winters Farm.

George Mount continued to farm this area even after it started to be used as a cricket ground. From Lord Sondes’ estate records for 1850, a 14-acre block of pasture was known as the cricket field, which suggests that only a few matches were played there and the rest of the time the land was used by Mount for grazing, probably as sheep pasture. Certainly Beverley Cricket Club had begun to play matches at St Lawrence in 1847, but Lord Sondes’ Club is also known to have used Lees Court, where his team played a match against Beverley Cricket Club in 1835.

The St Lawrence Club was formed in 1864 as a consequence of Lord Sondes’ enthusiasm for the game, but it seems the St Lawrence cricket field was still only used for a few games each season. Initially the facilities for players and spectators were basic. However conditions did improve after the club amalgamated with the famous Beverley Kent Club to form the Kent County Cricket Club, the two committees agreeing that St Lawrence would be the county cricket ground. Consequently several improvements were made to the ground in the 1870s, the cost borne by Lord Sondes, as landlord, and the cricket club from its funds. From a picture, published by Barraunds Ltd of London in 1877, the facilities included a number of large tents and a structure that looks like a wooden shed. On one side of the ground is a hedge and there are numerous trees, this parkland atmosphere was noted by contemporaries, the whole area said to be surrounded by hop fields. For the next twenty-five years this arrangement was retained but in 1896 the club purchased the ground and thereafter permanent buildings began to be constructed (prior to this date there had been a thatched wooden shed). A wooden pavilion was built in 1900, three years after the erection of a corrugated iron stand, although many of the structures around the ground were still tents. During the twentieth century, as can still be seen today, there was a considerable building programme, leading to the construction of numerous buildings beyond the boundary rope. As is even more obvious, recently there has been an increasing move to expand the activities available on the site, and even though cricket remains the primary focus, Kent Cricket Club has become a multipurpose venue used by other groups as well as by its staff and members. Such developments have necessarily had a considerable impact on the previously rural nature of the ground, as can be seen when comparing St Lawrence today with photographs of the ground from the late 1940s. Indeed in the last decade such changes have become even more pronounced and as always it is a matter of personal opinion whether this is for the better or not. However from a medievalist’s point of view, the biggest loss has been the missed chance to explore the archaeology of the site of this leper hospital. The limited ‘dig’, led by James Holman of Canterbury Archaeological Trust in this case, having found tantalising glimpses of what seems to have been a relatively prestigious daughter establishment of the great abbey of St Augustine.

To those who have got this far, apologies for the length but it seemed worth taking two ‘snapshots’ in time of this fascinating area of Canterbury. Next week, I promise, it will be shorter!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2706

2706