Firstly, congratulations to Dr Kaye Sowden who has received confirmation that her doctoral thesis on the history of early modern Pluckley has been signed off by her examiners and is therefore now completed. Well done Kaye!

A reminder: the Gender and Medieval Studies conference, 2nd to 5th July, at CCCU which is themed ‘Gender: Charity and Care’ https://medievalgender.co.uk/ and for bookings, please see: https://shop.canterbury.ac.uk/product-catalogue/faculty-of-arts-humanities/school-of-humanities This year the conference is followed on the Saturday by the ‘Canterbury Medieval Pageant’. Then on Sunday 6th July it will be the annual commemoration service of St Thomas More at St Dunstan’s church. The service begins at 7.30pm and this year the address will be given by Professor Robert Bartlett (Professor Emeritus at the University of St Andrew’s). There will be refreshments after the service and all are welcome to attend.

Now to this week which has plenty to cover, from the Kent MEMS Fest involving a panel comprising Peter Joyce, Kieron Hoyle and Jason Mazzocchi, my talk at Faversham, a workshop that I ran for a group of sixth formers at King’s School to the CKHH summer event on Wednesday, organised by Dr Claire Bartram.

Starting with MEMS Fest, I went to the first day on Friday and then on the Saturday I joined Jason Mazzocchi, Peter Joyce and Kieron Hoyle at 9am to chair their session entitled ‘Challenging Perceptions: Identity and Representation in Sixteenth-Century Kent’. Peter’s presentation explored the public persona of William Lambarde, a member of the Kent gentry who had a long career as a JP, which led him to produced two important works that offer insights into his attitude, as one of the governors, concerning those before him in the courts – the governed. For we have in his ’Exhortations’ evidence of what can be seen as an increasing fear of the dangers posed by the poor. This was against a background on the growing threat of war and ongoing economic strife, leading to harsher treatments and the desire to control the poor. Alongside this, the ‘Ephemeris’ comprises his notes covering the court cases at which he presided between June 1580 and September 1588. This juxtaposition is important because from Peter’s viewpoint concerning his assessment of charity and the poor in the lower Medway valley in Elizabeth’s reign, Lambarde’s notes, when set against the calendar of the assizes for Kent, suggest that Lambarde’s perception of a growth in criminal activity is misplaced, and that in reality, aside from robbery, the number of cases was not growing when corrected for the expanding population, Thus the question is why, what might be seen as behind his perception and what were the implications for those caught up in the justice system, as well as how did Lambarde’s deeply help Protestant views colour his actions – within the county judicial system and in his allied involvement in the growing number of new almshouses in west Kent, especially concerning the drawing up of the regulations governing such institutional care for the poor.

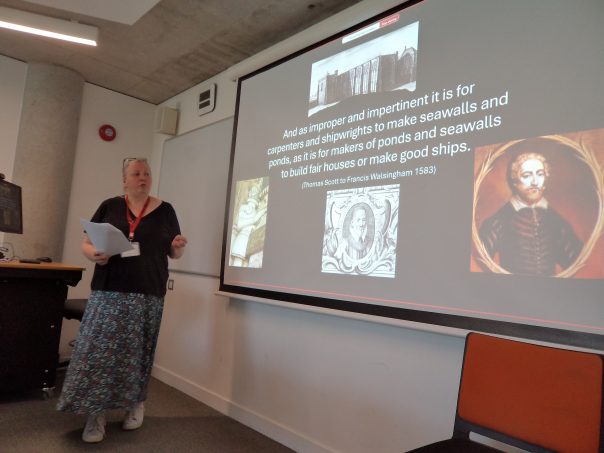

This raised some interesting ideas about authority and the role of central and local government which was to a degree taken up by Kieron who examined the shifting dynamics of expertise regarding the harbour works and the implementation of a victualling yard in Tudor Dover, with special reference to the early decades of Elizabeth’s reign. For as she said, under the early Tudor monarchs, Dover’s strategic position between London and Calais was critical for defence, trade and communication, and albeit Calais’ loss late in Mary’s reign raised issues, it was the poor state of Dover harbour that overwhelmingly exercised Elizabeth’s government. Consequently, this saw a shift away from local management towards projects under Crown-appointed professionals, and in particular Kieron examined the careers of three key individuals: Edward Baeshe, William Wynter and Thomas Digges. For it was Baeshe, as an extremely able administrator, who professionalised the victualling system for the Royal Navy, seeing the importance of standardising provisioning for vessels and ensuring such supplies would be available at a known number of south-eastern and southern coastal ports, including Dover.

At Dover, the obvious location for this victualling yard was seen as the Maison Dieu, the medieval pilgrim hospital even under its last master, Sir John Thompson, having become something of a store house for his activities under Henry VIII to enhance the harbour. The man heavily involved in transformation of the Maison Dieu to a victualling yard was William Wynter, who as an admiral worked closely with Baeshe and their considerable correspondence has given Kieron great insights into just how sophisticated the system was for its time. Equally important for Dover was the third of this trio because Digges, as a Kentish landowner, mathematician and hydraulic engineer, was instrumental in the harbour improvements, although it is interesting that many of the construction techniques were borrowed from the men of Romney Marsh, not from the Low Countries.

This, too, was fascinating and Jason, as the final presenter, picked up some of these threads because he investigated ideas about identity and representations of places by looking at networks and interrelations between and within communities, with special reference to the merchants and mariners of Faversham. By looking at the trading activities, other commercial activities, land and property holdings and wills, Jason highlighted the horizontal and vertical networks of several individuals within Faversham’s middling sort. Furthermore, some of these individuals were involved in the town’s civic government, and this extra dimension is also significant in the self-identification of such men within the town’s middling sort. Nor did such men confine their activities to Faversham, and their links with London and the Low Countries, as well as nearer to home in east Kent, have also provided Jason with interesting networks based on kinship and trade.

Furthermore, in thinking about identity and place, Jason examined the funeral monuments of two generations of the Sondes family in Throwley church, who although connected to those within Faversham’s middling sort were themselves members of the gentry. This provided an interesting contrast because, as he said, the portrayal of the elder Sondes wearing armour, his son in court dress, highlight matters of status and deference, which would have been widely understood by contemporaries and future viewers.

These three interesting presentations generated some questions, but because it was a tight schedule, the audience warmly applauded them and over coffee all three found themselves engaged in further discussions before the next session. I, too, was able to stay for this and then headed off to Faversham.

This year the public talks, organised by Fiona Palmer, were held in the Faversham Visitors’ Centre not the Guildhall, but this meant I picked up a few more people who had come on the off chance of getting in. Having called in ‘Living and Dying in Late Medieval Faversham’, I began by giving a very short introduction on the town’s pre-Conquest history before looking briefly at the foundation of the royal abbey, the implications for overlordship and the significance of the town’s archives, especially the early charters, including the town’s 1300 copy of the 1225 version of Magna Carta, and the slightly later custumal. With this contextual starting point, I was keen to explore ideas about the running of the late medieval town – horn blowing and civic elections, the various courts, how civic finances were raised, and other activities such as maintaining the urban environment through paving, designating only certain areas for the dumping of rubbish, and the daily ringing of the curfew bell. Thereafter, I moved on to looking at producers and traders to highlight the range of occupations undertaken in the town, how these were regulated and the important role of the town’s porters. My final sections took us to the town’s parish church, the range of daily services, the availability of polyphonic choral music by the early 16th century, the diversity of altars, images and other foci for devotion, and the special emphasis on the holy family. The final section explored funerals, associated services and matters concerning commemoration within late medieval religious practice. This generated questions from the audience and several people stayed on afterwards to ask more.

Questions were important on Monday when I had a group of Sixth Formers from the King’s School in the Cathedral Archives. Because this session was late in the day, I had only asked for five documents, but it was interesting that we were still there over an hour later and we could have gone on longer if some of the students hadn’t had to go to catch transport home. So many thanks to Cressida Williams for allowing us to stay longer than planned. Regarding what we looked at and discussed, firstly we looked at the first volume of Canterbury’s chamberlains’ accounts starting in the late 14th century. Moreover, keeping with the same period, we looked at two volumes of wills and deeds linked to the city. The first of these leather-bound books also has a list of annals, which gave the students a chance to try out their Latin and palaeography skills. By way of contrast, the final two books I had ordered were a Great Bible with its thought-provoking frontispiece and a Geneva Bible – both generating lots more questions.

To the final event for this week, it was the CKHH celebration organised by Claire Bartram. After Claire’s introduction, I did a short piece and this was followed by further short reports by Kieron Hoyle, Dr Katie McGown, Dr Ellie Williams, Jane Delamaine, Dr Sonia Overall, Michelle Crowther and Professor Carolyn Oulton, Dr Maria Diemling and Dr Heidi Stoner. Thereafter, we headed to Coleridge Gardens for tea and cake, thereby providing a good atmosphere where lots of networking took place. So thanks Claire for arranging this enjoyable and productive afternoon.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2356

2356