This week will give me a chance to catch up with what has been happening concerning the CKHH, which means I have two events to cover: Victoria Stevens’ presentation at the Kent Archives in Maidstone and the visit to the Canterbury Cathedral Glass Studio to see Professor Rachel Koopmans who is researching the ‘Kent window’, one of the Becket Miracle Windows from the north side of the Trinity Chapel.

Working chronologically, it was excellent to join Professor Carolyn Oulton, one of Victoria’s thesis supervisors, and members of the public who had gone to the Kent Library and History Centre at Maidstone for the last in the series of ‘lunchtime talks’ organised by Dr Mark Bateson of the Kent Archives Service. As he said, it has been a very successful series, and he is already in the process of putting together the programme for next year with a good number of speakers booked already – more once this is released.

In his introduction, Mark noted that Victoria is a professional conservator and has recently been appointed as head of conservation at West Dean College in West Sussex, which is internationally recognised for its excellence in the teaching of Arts, Design, Craft and Conservation. However, for the purposes of her presentation it was her recently completed MA by Research at CCCU which was the subject to be explored. For she has been investigating the inventory of heirlooms produced in 1903 following the death of William Oxenden Hammond, for the Hammond family who had been at St Albans Court in the parish of Nonington since the early 16th century. As a yeoman family who had begun as tenant farmers of St Alban’s Abbey in Henry VIII’s reign, the Hammonds were one of a number of aspiring families who would benefit from the Dissolution and seek to become members of the county gentry. This involved various commercial activities, marriage alliances, entry into politics and local government such as sitting on the bench as a JP, education including sending sons to university and developing a cultured taste for books, portraiture, and other works of art. Thus, in Leland’s terms, they saw themselves among the ‘governors’, the elite minority in society rather than the majority of the ‘governed’, negotiating their way through the reigns of the later Tudors and the early Stuarts, and, as royalists, navigating the Civil War and Commonwealth periods. Thereafter the family were in more comfortable territory during the reigns of the later Stuarts, the Hanoverians and into the Victorian age. For their houses, gardens and especially their collections highlighted the familial characteristics of social ambition, engagement in cultured activities from classical to other forms of literature, travel and social conservatism, the epitome of culture, taste, pedigree and wealth. Yet like many other such families the early 20th century brought major issues in the form of a lack of heirs, WWI, the financial crises of the inter-war years and death duties, which meant the grand house was sold in 1938.

But to go back to earlier Hammonds, it was Sir Thomas Hammond, knighted in 1548, who three years later advanced from tenant to owner of St Albans Court when he purchased the place and within a few years was busy rebuilding the house in brick, the fashionable ‘new’ building material. Such a move was an outward sign of his enhanced social status and subsequent generations followed his example. Indeed, within the estate the Hammonds constructed/redesigned three houses at various times, Sir Thomas’ Tudor house followed by a re-orientated, larger17th-century house (having Restoration and then Georgian additions) and finally the Victorian architect George Devey’s (new) St Albans Court built on higher ground which is in the style of a grand Elizabethan mansion. Moreover, this involved removing certain fireplaces, originally from Northbourne Court, the family home of the Sandes family linked to the Hammonds through marriage, which had been taken firstly to (old) St Albans before their final relocation to the new Victorian house. Another feature of this house that can be viewed as projecting the cultural aspirations of the Hammonds is the vista of the new house from the road, and equally the view from the house of what had become Old St Albans Court, re-established as a Tudor house once the later additions had been removed.

Such ways of seeing and been seen would have been equally pertinent within the Victorian house itself, for as well as effectively being one room thick on three sides to partly enclose a large open space, not dissimilar to a grand cloister garth, William Oxenden Hammond might be viewed as having a four-room inner sanctum comprising his library with other rooms including his gun room – he was keen on shooting birds which were stuffed and displayed in paintings. As Victoria said, he understood what a library should look like and he therefore had ensured that it had double windows and a double aspect, as well as an ornate plaster ceiling. It, like the family portraits and other paintings proclaimed taste, education, and culture, for among the artists they had commissioned were Reynolds and Gainsborough. Nor was this all because various Hammonds had brought back objects from their travels, were very interested in travel literature and science, admired literary pursuits and wrote poetry. Evidence of all these strands can be found in the books listed within the 1903 inventory, as well as part of the plate and silver collection and the paintings, in part financed through the family’s own bank, which they had established in Canterbury in 1788. Such a financial undertaking was also in keeping with the family’s position in east Kent society, as are the many memorials to family members in the parish church at Nonington.

All of these aspects have been investigated by Victoria, who has linked specific members of the family to ‘their’ books and other objects within the inventory, and this close reading and biographical research generated questions from the interested audience after her presentation. And as a final point, Victoria is sure the family would have had bookplates in their books, but so far, she has had very little success discovering books from the library. For before the main sale dealers sold the choicest to American buyers but tracking them has proved very tricky. However, Victoria has not given up and if anyone has any information, please do get in touch. Thus ended a fascinating presentation as Mark said and as evidenced by the number and variety of questions afterwards.

For my second report about an event from last week, I’ll leave aside the Lossenham wills group meeting down at Lossenham being unable to attend because I was teaching and instead mention the visit to Canterbury Cathedral Glass Studio to see some of the 6 panels that Professor Rachel Koopmans (University of Toronto) has so far investigated, there being 16 in all. The sponsors of Rachel’s research are the Friends of the Cathedral, the Oldham Trust and the Oxus Foundation, and I believe there will be a conference early next year in conjunction with MEMS at Kent, but for this visit the beneficiaries were a group of American students who are over for a term at CCCU, their college tutor and the head of their college who was on a short visit. Like the previous windows, Rachel and Leonie Seliger will produce a book for this window but for today I just want to give you a flavour of what they have been investigating.

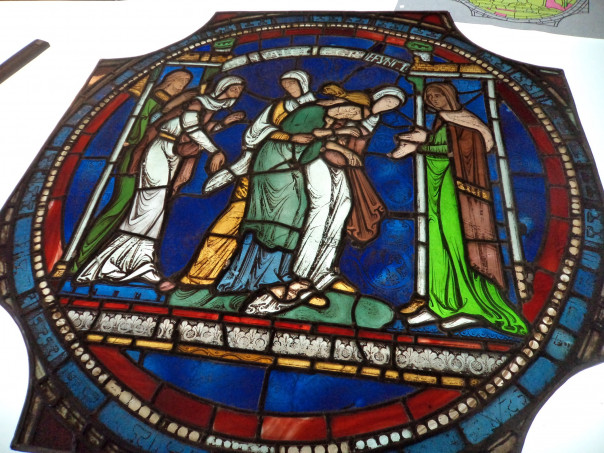

In some ways, this window is unlike any of the other Miracle Windows and Rachel and Leonie Seliger, Head of the Glass Studio, think that this window was made as a presentation piece for the monks after they returned to Canterbury following their time in exile in France when there had been a hiatus in terms of rebuilding the Trinity Chapel. This group of French glaziers were top class artists and craftsmen and therefore in a position to confidently undertake such a window to showcase the extraordinary and innovative quality of their work.

Now almost all the miracle narratives in this window concern miracles relating to people from Kent, but the top 2 panels concern a knight called Richard from Yorkshire, and to be more precise from Stanley which Rachel thinks is the place south of York rather than in Durham, which does indeed seem likely. However, it would be very interesting to explore whether he had any Kent connections at all because for the rest of this window that seems to be the common denominator. Consequently, the images here come from the 2 panels of William of Dene and one from Goditha – both Kent miracles.

As Rachel said, this is very much a matter of looking very carefully because the panels do not give up their secrets easily. Nevertheless, for these first panels and as a starting point Leonie and Rachel had now plotted out what is early 13th-century glass, what is material added in the 19th century by Austin and what was altered in the early 20th century by Caldwell jnr. Other topics investigated are the inscriptions, including working on the different letters, words and phrases, as well as how they might have been used by the monks and clerks for the benefit of the early pilgrims. They are equally interested in the colour schemes used by the glaziers, the remarkable quality of the painting, the processes involved concerning the decoration, and the way the framing was constructed and used for the glass. Thinking about the portrayal of narrative is similarly important, such as how to indicate movement in what is essentially a static scene, one way being to frame those involved between two different sized doors within a single scene, or when this moves between one scene and the next, the reference through a repetition of colour of a person’s clothing as well as the discarding of a single garment or other object. For example, look at the two images from William of Dene to see the three items he has discarded in the second panel.

Rachel very generously gave up much of last Wednesday afternoon to discuss these and other fascinating points and we had a brilliant visit, thereby giving everyone new insights into these panels and the window more broadly. So do watch this space and there will be more updates as the research work progresses, and next week I’ll give you a report about Abi Kingsnorth’s presentation to the Kent History Postgraduates.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1723

1723