Firstly, just a reminder that this Saturday it is the Medway History Showcase 24 at the Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham where Kieron Hoyle and Jason Mazzocchi will be looking after the CKHH stall, while I’ll be at the KAS Historic Buildings conference at Aylesford Priory. I intend to have reports from both events next week.

Turning to this week, apologies but this is going to be a long report and four people have contributed to it, I’ll signal whose is what as we go through because the Society of Landscape Studies weekend in Canterbury comprised a very busy couple of days. On Saturday, members of the Society and others, mainly from Kent, gathered at St Paul’s church for the conference, and having done the usual housekeeping, Professor Charles Watkins, on behalf of the Society, welcomed everyone to this annual conference which had been organised jointly by Drs Hadrian Cook and Jeremy Lake for the Society with the Centre for Kent History and Heritage at CCCU.

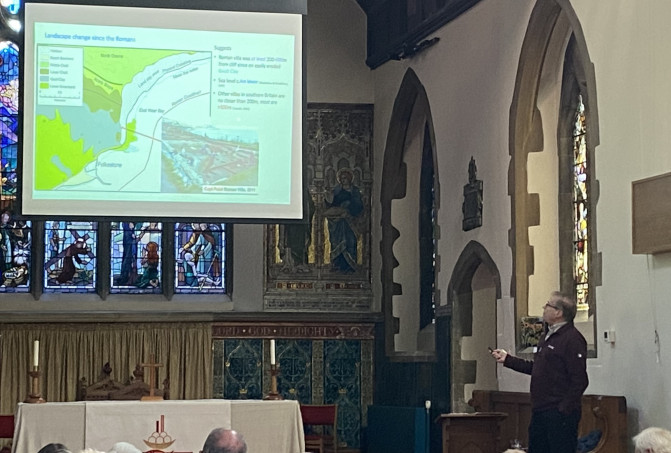

As the first speaker of the day in the session entitles ‘Exploring Kent landscapes‘, Dr Chris Young provided a fascinating overview of the landscape changes that have taken place along Kent’s coastline from before the arrival of the Romans up to the present day. For being part of the great Wealden dome, which in geological time extended to France, Belgium and the Netherlands, Kent’s coastline is complex. For it includes a mix of chalk cliffs sitting on a gault clay base from Folkestone eastwards round almost to the Isle of Thanet, where again the chalk outcrops, the London clay cliffs of the north Kent coast and low-lying coastal marshlands with gravel spits, especially the Romney Marshes and those around Worth and Sandwich, as well as the north Kent marshes. As Chris explained, these coastal landscapes have been subject in varying, complex and often dynamic ways to erosion and deposition – as in the chalk cliffs falls at Folkestone or the loss of Dover’s harbour through the silting up of the port which saw vast fortunes spent to try to reverse matters in the sixteenth century. Although these changes were often the result of the prevailing westerlies and longshore drift, events such as the ‘Great Storms’ of the thirteenth century are equally important and cliff erosion, while a product of wave action and exposure at the base, need to factor in fractures widened by prolonged rainfall and frost at the top. As he noted the rate of cliff retreat varies considerably over space and time, and in the recent past has been affected by human activities, such as the use of groins which have disrupted the movement of sediments. To illustrate this dynamic nature of the Kent coastline, Chris showed us how much coast has been lost at Folkestone Warren since Roman times and a series of photos and postcards of Kingsdown to illustrate how the beach has disappeared due to sediment starvation. While the rate of retreat of the chalk cliffs at the Warren in the late nineteenth century appear to have been between 0.1 and 3.6 m per year, in comparison, the London clay cliffs at St James’ church, Warden, on the Isle of Sheppey have been and indeed continue to be eroded at between 3.5 to 4 metres annually. Furthermore, as he pointed out it is important to factor in that during Roman times the sea level was 4 metres lower than today and in the historic past erosion was faster due to the Little Ice Age (1400-1850) being cold, wet and stormy. Thus, we ignore historic landscape change at our peril and Canute really did know a thing or to, even if his flattering courtiers did not!

Professor Peter Vujakovic gave us a very different approach to exploring the Kentish landscape through his adaptation of a biographical approach. His opening slides of a view of the Kent Downs at Wye as first rough pasture traversed by a footpath and then completely changed in his mind’s eye to vivid yellow, stumped the audience until Peter provided an explanation. He thinks that having used an OS land-use map of the area with students on fieldtrips to the Downs on numerous occasions, his brain had in a sense supplanted reality with the map. This has only happened once but such carto-synaethesia as he called it brought him to thinking about the map in new ways. Drawing on the work of Brian Harley and the idea of the map as biography, Peter took us on his journey where the map as autobiography, in Harley’s terms, got him thinking about a specific map which shows the area around Ashford where he did much of his teaching and research field visits. This he saw as ‘his patch’, not only in his professional life but as someone who walked the area, went foraging and saw the place as home, thereby bringing to the fore the sense of place in both time and space. This brought in ideas about Tim Ingold’s concept of taskscape to add to the mix where the landscape through its features has been a range of working landscapes, each one overlaid on what had gone before as a palimpsest, yet potentially also cutting into early landscapes both on the ground and as portrayed by the cartographer. Peter also pointed out the importance of memory and that these earlier uses can also be preserved in the place names that can evoke the people as well as their activities in the historic landscape. Moreover, this can also be used playfully, as in Russell Hoban’s cult novel Riddley Walker. This thought-provoking presentation provided a great foil for Chris’ assessment of Kent’s coastal landscapes to give the audience a flavour of the rich diversity to be found in the county.

The reports for the next two speakers, a session entitled ‘Landscapes of authority in medieval Kent’, are by Charles Watkins. Richard Eales gave a stimulating talk on Norman castles in the medieval landscape. He set the scene by considering changes in the historiography of castle studies. Until the 1960s castles were seen as primarily defensive structures but since then they have become recognised as multifunctional symbols of power. The current view is that they can be identified as examples of castellated conspicuous consumption. Moreover, the context of castles, the ways that they were approached, the landscapes, parks and gardens which surrounded them, indicate that to some extent they were at the centre of decorative landscapes. Richard then focussed on the building of castles in Kent. He stressed that there is very little documentary evidence available, and their early history remains mysterious. The evidence suggests that just over 20 Norman castles were built in Kent, which was the earliest landscape to be settled by the Normans. A series of palatial royal castles were built at key sites: Dover, Canterbury, Rochester, on the route from Dover to London. These castles protected existing important settlements. At Canterbury the Norman motte is likely to be very early, and Rochester probably dates from the 1120s and 1130s. Other non-royal castles, such as Tonbridge castle held by the de Clare family, were usually built in the centre of large, landed estates. Several castles were built in periods of peace, with the proceeds of war, rather than as military endeavours during wars. Richard concluded by emphasising that there is an awful amount we don’t know about castles in Kent, that their military importance is still a question of debate and there is need for greater use of modern surveying techniques. And Norman castles continue to be discovered, such as Newnham Castle, which had been completely levelled, but which was confirmed by excavation in 2012.

Tim Tatton-Brown gave a characteristically erudite and highly informative lecture on the landscape around Canterbury in the Anglo-Norman period. This was based on subtle scholarship and detailed analysis of a range of historical documents and maps, and the evidence of the landscape itself. He demonstrated the enormous importance of the major ecclesiastical estates around Canterbury, including vast areas of land held by Minster Abbey, Reculver Abbey, St Augustine’s Abbey and the lands of Archbishop and Community. At Domesday there were three main manors around Canterbury. Dungeon Manor was most likely owned by King William’s half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent (d. 1097). The estate of Chislet, belonging to St Augustine’s Abbey, was active in the reclamation of marshland and running salt works. Tim emphasized the importance of swine pasturing in the woods of Blean. He also explained the key importance of Archbishop Lanfranc (c.1010–1089), who was born in Pavia, and was made archbishop four years after the Norman conquest. Lanfranc was instrumental in the building of churches in Canterbury in addition to the cathedral. Some of the building work he ordered at St Gregory’s Priory survives in its alms houses, including extraordinarily a loo which seems to have been in continuous use from the eleventh century to the late twentieth century. Tim’s talk emphasized the importance of key individuals in forming the landscapes around Canterbury after the Norman Conquest.

That brought us to the end of the morning sessions and everyone headed into the church hall where Jackie Curd and her team of helpers from the church had prepared an excellent lunch. It is also well worth saying that they had already provided everyone with two lots of refreshments: before the conference started and between the first and second sessions. After lunch it was agreed that we should hold the afternoon sessions in the church hall. This third session was entitled ‘East Kent as Gateway: to enter and defend’.

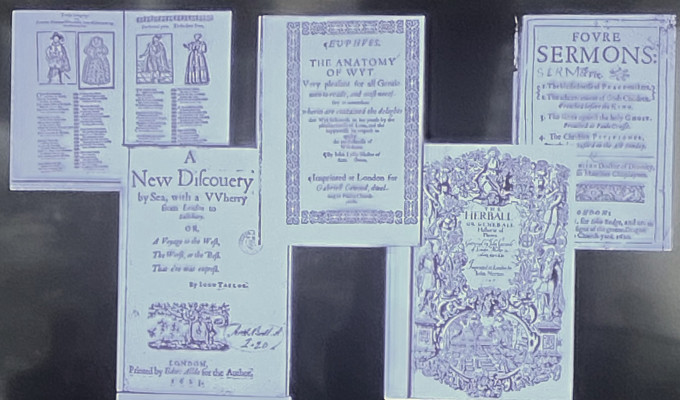

Thinking about the ways landscapes were portrayed by early modern writers in a wide range of fields, Dr Claire Bartram offered a thoughtful assessment of how Dover had been envisaged and what may have been the motivation of such portrayals politically, socially and in religious terms. For this imagined Dover with its white cliffs, castle and harbour has been an enduring feature, again used to great effect in the WWII propaganda with the addition of a spitfire. Taking as her first literary text King Lear and the imagined cliff scene, she highlighted how the illusion of Dover’s cliffs is portrayed by ‘Poor Tom’ (Edgar in disguise) in his word picture to Gloucester, his blind father, who wishes to throw himself off the cliff. Moreover, by focusing solely on what he is ‘seeing’ from the imagined cliff top, Edgar description of birds the size of beetles and the fishermen the size of mice down on the beach creates the illusion of the vastness of Dover’s cliffs thereby completely disorientating his father. This sense of the majesty of the Dover landscape where sea and land meet is also evident in the plans produced in the later sixteenth century, primarily in relation to the various proposed new harbour works which were the product of detailed and far more accurate surveying. These depict not only landmarks on shore but also great ships just offshore, thereby denoting Dover as a safe haven and gateway for people and goods. Such ideas were equally displayed in textual form, whether in John Lyly’s prose fiction of a group of travellers who enjoy hospitality at Dover or John Gerard’s seventeenth-century herbal that features the plants the traveller will see when travelling through Kent to Dover. The deployment of Dover continued through the Civil War period, albeit for Mildmay Fane this might be in terms of waiting for a better, that is calmer time, which came with the Restoration. Consequently, the richness of this topic was clear from Claire’s presentation, and that while some writers had used natural and man-made features of the landscape, others had focused on the port as a place of arrival or departure, the voyage ahead or just completed available to be used by the writer literally or figuratively.

Dr Andrew Richardson also drew on the iconic image of the spitfire against the background of the White Cliffs of Dover, seeing this as emblematic of the national consciousness of Dover’s and England’s defence against attack from outside forces. For his interesting presentation covering Kent’s modern military landscape, he discussed the period from 1900 to 2024 and how in addition to the two World Wars this has seen cycles of investment in defence spending, which has left a considerable number and range of features in the landscape, some of which are now being re-discovered and will inform new audiences about the role this corner of England has played in modern times. Taking as his first example, Andrew looked to the west of Dover and the three concrete casements, and their great guns constructed at the beginning of the twentieth century. Because prior to the Entente Cordiale signed in 1904, for centuries the ‘enemy’ had been seen as the French, but this now changed as would become apparent. Other military features in the landscape of note linked to WWI are the mock trench system constructed at Barham to provide a place to train troops for the Western Front, the extensive port with its railway at Richborough and at Capel le Ferne a huge structure for the Royal Naval airships, which would later become a caravan park, although the woods to the north contained concrete blocks use to moor these airships that were used to patrol the English Channel on the lookout for submarines. The 1920s saw the construction of the sound mirrors, as at Abbot’s Cliff, which were intended to pick-up the sound of incoming aircraft, and while they were short-lived and produced on a small budget, they were valuable contributors to the development of radar. This was part of the realisation of the potential dangers of airborne attack in the run-up to WWII from an enemy across the Dover Straits and during the 1930s there was increasing investment in anti-aircraft installations near Dover. Such provisions were seen to be bolstered by the network of pill boxes, some of which have survived, their positions recently plotted by archaeologists working in the field. The Cold War between 1947 and 1991 also resulted in further installations such as nuclear bunkers, but since then many of the county’s military bases have closed as the army has become a smaller, professional force.

After a further break for tea/coffee and scones, we moved to the final session of the day on ‘Seeing new landscapes’. This session brought new ways of thinking about landscapes, Greg Taylor providing a fascinating report on how the Wealden dome, also discussed by Chris at the beginning of the day, can form the basis of a Cross-Channel Geopark. For this large area of unified geology is of international significance, its visual impact across the Channel due to the final breaching of the Dover Strait and subsequent erosion and cliff retreat to produce the distinctive White Cliffs. Moreover, with the increasing emphasis on global sea-level change where climate change and sustainability are seen as major factors, there is a desire on both sides of the Channel to seek to protect these areas. This would seem to be very much in keeping with the idea of the UNESCO Geoparks which are classified as areas with internationally important rocks and landscapes, all of which are managed responsibly. Now as Greg said, applying for this status will be extremely competitive for it will put them up against sites from across the world, not least because of the Geoparks so far designated, there are a considerable number in Europe already. The Chinese have also seen the value of this designation, but the United States has not, while the large mining companies in Australia have probably stifled any such Geoparks there. Concerning the application process, a good start has been made and the bid has been being supported by the Heritage Fund and DEFRA, as well as the two Canterbury-based universities. Outreach to bring in the general public is a key constituent and such activities undertaken thus far have included creative writing and moth trapping with more planned for the future, in part through the website. Indeed, the website contains resources for groups to use themselves. If all goes well it is hoped that this status will be achieved by the Spring of 2027. As Greg concluded, building local initiatives has been an important part of the project, seen through the series of ‘Geosites’, some primarily geological but with others based around biodiversity. Most are onshore across Kent on this side of the Channel but includes some marine geosites incorporating underwater features such as plunge pools from the mega flood, as well as shipwrecks.

Our final presenter, Dr Catriona Cooper began by pointing out that she is an archaeologist by training, and her primary interest is in buildings and landscapes. She was a leading member of the ‘Lived experience in the later Middle Ages’ project that focused on comparing the lived experience at Bodiam Castle, just into Sussex and Ightham Mote, a moated manor house in west Kent. The project was led by Professor Matthew Johnson and while not ignoring the castles’ debate over military or multipurpose structures, the team was keen to examine these sites more imaginatively using modern surveying and other techniques, both inside and outside, and by setting the building in its historic landscape. Although it was not feasible to use all the techniques the team had wanted, they were able to use ideas such as Ingold’s taskscape, the technique Peter had mentioned in the morning, in terms of iron-working nearby. Furthermore, by deploying a spatial datebase, they had explored what could have been seen by those approaching from different angles and directions, and by those looking out from the sites themselves, especially when taking account of the watercourses, which for Bodiam was the still tidal River Rother during the later medieval period. These ideas were fascinating, but the use of new digital techniques to in a sense map the interior is even more exciting. Looking at the importance of the undercroft and the room spaces above at both buildings comparatively offered ways of exploring how people thought about and interacted with these spaces, not only in terms of sight but also other senses, especially hearing. Catriona’s presentation was a great way to end the sessions before the roundtable because she had illustrated some of the ways cutting-edge landscape studies are going as digital technologies become ever-more advanced, thereby not just putting people into buildings but analysing their potential sensory lived experience too.

After a roundtable session chaired by Hadrian Cook, this brought us to the end of what everyone agreed had been a fascinating and often thought-provoking day. Furthermore, there had been interesting links between people’s presentations, sometimes unexpected, and what was clear was that Kent’s rich landscape was both complex and dynamic, thereby setting the scene for Sunday’s fieldtrips. However, before people dispersed, some meeting up again in the evening at The Two Sawyers, we thanked Jackie Curd for making us so welcome to St Paul’s church and for not only the great refreshments but for help with the AV too.

Moving to Sunday, those going on the fieldtrips to Dover and Nonington met the extremely helpful coach driver the following morning. The report on the fieldtrip to Dover’s Western Heights is by Jason Mazzocchi. Early on Sunday morning, 15 delegates gathered and were led by Keith Parfitt to discover nineteenth- and twentieth-century landscapes on a field trip to Dover’s Western Heights. With some optimism for a dry day, the group began their tour by meeting at the round Knights Templar medieval church. The foundation of this small medieval chapel stands on the Western Heights, built in the twelfth century, it had a circular nave and a rectangular chancel standing on flint.

The attendees then embarked on a 90-minute walk/ tour on the chilly cliff tops of Dover. Keith introduced a splendid view from the top of the Western Heights which overlook the port of Dover with the commercial eastern docks to the left of the panoramic view, and the western docks below our standpoint. Our attention was drawn across the English Channel to France to provide a sense of proximity and landscape to Dover. It was easy to judge that Dover was the gateway to the sea and the Continent. After a brief presentation on the history of the docks and defences, including Archcliffe Fort, Keith then took the group to the St Martins Battery Windows, constructed between 1871-74. The impressive emplacements had gone through a series of modifications and Keith explained the periodically different brickwork, and how the powder rooms had window hatches for lights to be placed by soldiers who also had to cover their hobnail boots with material to stop causing sparks and fatal explosions!

The group then walked to the Drop Redoubt which was accessed by footpath and walking through a small tunnel. The Drop Redoubt is one of the two forts on the Western Heights; the other being the Citadel, and the two are linked by a series of dry moats (or lines). The artillery at the Redoubt faced mostly inland – as Keith explained it was intended to be used to attack an invading force attempting to capture Dover from the north-east. The brickwork was spectacular and the form of the Drop Redoubt was a pentagon, formed by cutting trenches into the hillside and revetting them with bricks. A striking feature of the landscape of brickwork is the five vaulted casemates:

The group then headed to the North entrance which was the fortified access to the Western Heights. Its defences were substantial, comprising two bridges and a tunnel. This entrance is nearest to the town and was evident as the group looked across the valley in an advantageous viewpoint across the town. Keith explained the unpopularity of the the cutting of the present road through the North Lines – to allow road widening for heavy vehicles, and the demolition of the southern entrance for the same reason – which has destroyed the integrity of the fortress.

The afternoon report is by Kieron Hoyle. Following a lovely lunch at Little Farthingloe Farm we headed to Nonington and Peter Hobbs‘ house, Old St Albans Court. Keith Parfitt, who has been studying the site for many years gave us a short talk with slides on the archaeological work that had been carried out since the first dig in 1997, this included the 17-18th-century brick clamp, the Anglo-Saxon cemeteries and work on the buildings and ground of Old St Albans Court itself. This was followed by a tour conducted by Peter which explained the centuries of building and rebuilding and the accidental invention of mock Tudor architecture. Peter explained the origins of the estate which is believed to be that of a Saxon estate Oesewalum and recorded in Domesay as Eswalt. The tour took the group around the grounds taking in the Tudor garden, fishponds, the rebuilding of Beech Grove and the Pulham gardens.

We then accompanied Keith up towards the woodland where they had kindly kept the trenches showing a well and medieval foundations open for an extra few weeks to allow us to examine them. This really brought the story of the estate and its geography together and also meant we were able to see various features of the surrounding village and the site of the brick clamps.

We headed back down to the warmth of the stables and spent some time looking at the mass of books, photographs maps and documents Peter holds concerning the history of his home and the estate. It was then time to give our thanks to both Peter and Keith and return to Canterbury.

On behalf of CKHH, I would like to thank all the speakers on both days, St Paul’s church and Peter Hobbs for hosting us, to the SLS committee, to Jason and Kieron and finally, but extremely importantly, those who came on one or both days – it was a great success!

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 2558

2558

What an interesting conference and I much regret I was unable to attend the Saturday. Amongst many other things, I was struck by the suggestion that the sea was 4 metres lower in Roman times and if so, how I wondered how this is corroborated in Roman sites like Richborough, Dover, East Wear Bay and Lympne to mention only a few.

Thanks Peter and I think the best idea would be to ask Dr Chris Young, as well as looking at ‘Maritime Kent through the Ages’ where he discusses this topic in the opening chapter. Best wishes, Sheila.

One point to make about Tim Tatton Brown’s otherwise excellent talk. Reculver minster’s lands mentioned in the 10th century Anglo Saxon Charter, Sawyer 546, included 4 sulungs on the Isle of Thanet. This was given in the lecture as at St Nicholas at Wade; but, according to more recent work by Nicholas Brooks and Susan Kelly, this estate may have been at Sarre (see Charters of Christ Church, ed. Brooks & Kelly; and Reculver Minster and its early charters, Kelly, 74-5, n.39)

Thanks very much, good to have this and land at Sarre would have been strategically important. Regards, Sheila