Now that we are into September, and more importantly I am back from the Fifteenth Century conference at St John’s College, Oxford, last week, I thought I would start with the forthcoming events from CKHH before a very short report on medieval Canterbury chaplains at Oxford and a bit longer one on Canterbury’s medieval churches and parishioners for the Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society last night.

Just to mention first, the Lossenham Project wills group had a very productive meeting online today. In particular, as well as transcribing the probate materials and this featuring in the Project’s latest edition of the newsletter with articles/reports by Celia and Jason: https://mcusercontent.com/df0ed3bd3f81ea3c86a703290/files/2907a469-4ca6-d7d1-0e5d-13ec176399b4/The_Lossenham_Project_Newsletter_Issue_29.pdf , it is great to have other group members reporting on using the data from these materials, both quantitatively and qualitatively, for academic work and for public engagement – history and heritage!

So to upcoming events, as noted before, one of the highlights of the CKHH year is the Nightingale Memorial Lecture. This joint annual lecture organised by the Centre and Brook Rural Museum will be held at Canterbury Christ Church in the Michael Berry Lecture Theatre, Old Sessions House at 7pm on Tuesday 24 September. This will be preceded by a wine reception at 6.30pm and before the lecture the Sheriff of Canterbury will present Ian Coulson Memorial Postgraduate Award certificates. This year the Nightingale Lecture will be given by Dr John Bulaitis entitled ‘Book Launch – Tales from The Tithe War’ and the CCCU Bookshop will be present with copies for sale of John’s new book on this fascinating topic. The event is free but there will be a retiring collection split between the Museum and the Ian Coulson Fund.

Looking to the following weekend: Saturday 28th and Sunday 29th September, the CKHH is delighted to be working with the Society of Landscape Studies to hold a weekend at Canterbury under the title ‘Sacred and Profane: the landscapes of Kent’. The conference will take place on the Saturday at St Paul’s church, Canterbury, near the Burgate and among the presenters will be Tim Tatton-Brown, Richard Eales and past and present members of CCCU staff, including among the former Dr Chris Young (see his excellent opening chapter in Maritime Kent on the county’s physical geography over time) and among the latter Dr Claire Bartram, one of the Centre’s co-directors, and Dr Catriona Cooper, a digital history specialist. The field trip on the Sunday will begin and end in Canterbury and includes guided visits by Keith Parfitt to Dover’s Western Heights and an Anglo-Saxon and medieval landscape at Old St Alban’s Court, Nonington. More details and booking at: https://www.landscapestudies.com/sls-annual-conference-september-2024/

Moving very slightly into October, it will be the Medway History Showcase on Saturday, 5 October and it is even better and bigger than last year. Once again, the CKHH is delighted to be involved because this unique event, the most prominent heritage gathering in North Kent, brings together all the major heritage partners alongside others that you may not have heard of but who do fantastic work in their communities. The History Showcase idea started in 2021 as part of the Institute of Historical Research’s (IHR) centenary celebrations. Since then, it has gone from strength to strength with events in Medway at the excellent Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham, as well as at Canterbury and Dover.

There will be eight accessible talks, including by Jason Mazzocchi, a doctoral postgraduate student and member of the Centre, and these will all focus on themes pertinent to Medway’s history and heritage. In addition, the organisers are welcoming history and heritage organisations as exhibitors; so far, twenty-six have confirmed, although there is room for more! Those present will be delighted to discuss their activities, and there will be plenty of time for such discussions during the day.

This is free to pre-booked ticket holders, including free access to the beautiful Royal Engineers Museum and its café facilities. The Medway History Showcase is open to all ages, especially families, making it a great day to explore what happened in the past and what it may mean for today and the future. Tickets can be booked via https://re-museum.digitickets.co.uk/event-tickets/52565?catID=51206& and for further information or if your history or heritage organisation would like to exhibit on the day please email Pete or Jane at Medwayhs24@gmail.com

To Oxford, and among the highlights of the conference was a visit to the muniments tower at New College which was founded by Bishop Wykeham in the late 14th century. The college’s endowment involves lands from the alien priories, including one manor in Kent which I’m hoping to investigate when I have the time. The archivist at New College is well known to those who have worked in Canterbury Cathedral archives because it is Dr Michael Stansfield, and he gave us a thoroughly interesting tour of the college’s extensive medieval muniments.

From the start, education was an important part of the college’s ethos, as well as praying for Wykeham’s soul and you could say that the paper I delivered at the conference shared similar themes because I was exploring the networks involving clerics inside and outside the cathedral precincts. Those inside were either chantry chaplains or those at the almonry chapel and school, while those outside included more chantry chaplains at several of the city’s parish churches, as well as parish clergy more broadly in Canterbury. Not all the connections involved book bequests, but many did, and such links similarly involved other personal items and that some of these clerics wanted other clerics to be their executors. Just to give one example, John Clerke, chaplain at the almonry sought to aid his fellow clerics there by giving some of his liturgical books to John Gower and Laurence Gyle, such bequests in turn helping them collectively. Additionally, he bequeathed his copy of Pars Oculi to Gower, while Gyle was the recipient of Clerke’s Latin copy of the popular work, The Golden Legend. Gyle was also named as Clerke’s executor, but interestingly what might be seen as more person items including one of Clerke’s best bed hangings with the tester, a canopy with 3 blue curtains, several items of bedding and two of his best gowns and cowls were bequeathed to Gower. Moreover, as well as such personally directed giving, Clerke can be seen as distributing tokens of friendship towards his community – he intended that his antiphonal should be used in the almonry chapel by the serving priest after his death.

Nor, of course, were such networks only to be found in Canterbury and Dr Paul Lee in his doctoral thesis on Dartford Priory within the context of the diocese of Rochester uncovered a similar network of clerics at Rochester in the cathedral and city who were bequeathing books amongst other items. Although a small network, this was also the case involving the Maison Dieu at Dover and there is, of course, John Mower’s (vicar of Tenterden) famous will that is full of book bequests.

However, coming back to Canterbury and moving on to last night, it was great to see a good number of people at St Paul’s church for the first of CHAS’s lectures for 2024/25, especially because the road nearby had been unexpectedly closed due it would seem to a burst water main. My title was ‘Canterbury’s Medieval Churches: Parish and People’ and as I explained I was going to concentrate on how parishioners living in late medieval Canterbury interacted with their churches rather than provide an architectural history. For those interested in the development of the church buildings, Tim Tatton-Brown’s diocesan surveys are very useful and there is his article in Slater and Rosser (eds), The Church in the Medieval Town (1998), as well as more recent CAT reports.

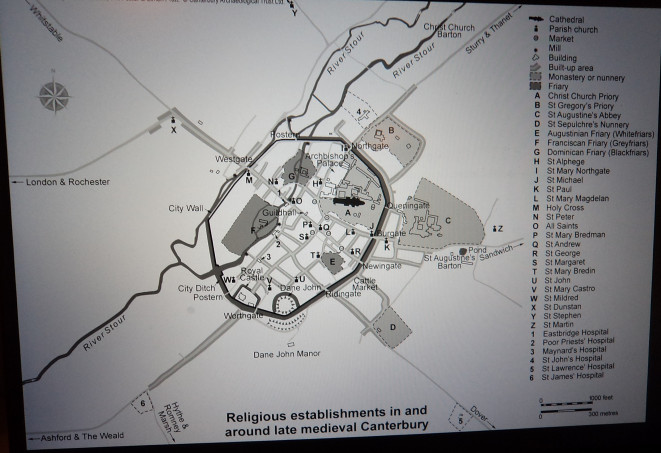

My talk was in three sections which meant that we firstly explored the number, location, and size of the city’s parish churches and how and why they developed from a few before the Conquest to almost 20 in the later Middle Ages. This involved looking at the importance in the city of the great ecclesiastical institutions of St Augustine’s Abbey and the archbishop and his community at Christ Church, and then from Archbishop Lanfranc’s time the see as one entity and Christ Church Priory as another. For as landholders with jurisdictional rights, they all had spheres of influence that meant they were keen and able to build numerous churches. This was true before the Conquest but was far more evident thereafter and as the parochial system came into being, the city’s churches were all under the patronage of one of these three great ecclesiastical powerhouses. And as an aside, we looked at the role of the lay cemeteries at St Augustine’s and the cathedral for the laity at many of these parish churches.

Moving on to the meat of the talk, the next section began by examining different aspects of parish and people beginning with an investigation of parish worship from the daily services to feast days. However, firstly we looked at the importance of symbolism within the church and that there was seen to be divine meaning in everything. Having mentioned the 4 layers of meaning, it was a matter of giving some examples such as the pillars – bishops and doctors who sustain the church or the 4 walls – the cardinal virtues of fortitude, justice, temperance and prudence. Then having thought about location, the availability of space, the wealth of patrons, and the identities of the parishioners, we compared two churches held by St Augustine’s Abbey: St Mildred’s on the periphery of the city where there is plenty of space and St Andrew’s right in the centre but with virtually no room to expand. The last part of this section considered the round of daily services and then the proliferation of feast days, as well as how and what the parishioners were expected to provide for their church, and how these Canterbury churches had far more than the minimum requirements as revealed in wills and the inventories from St Dunstan’s and St Andrew’s churches within their respective churchwardens’ accounts.

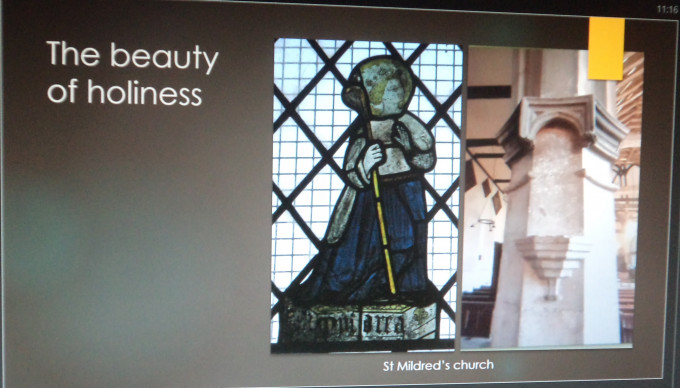

The next part explored the beauty of holiness, especially regarding the support of the parish’s saints. What was clear was that there were certain ‘common’ saints but that there was still considerable variation between parishes and although the size of the church might be expected to be important, this was not always clear. For example, the far larger church of St Mildred had around 11 devotional sites whereas the much small St Andrew’s church had at least 16. We also looked at how the parishioners engaged with ‘their’ saints, such as Margaret Cherche of St Alphage’s parish who wanted for 5 years after her death the placement of a 5 lb wax candle with her name on it at the image of Our Lady next to the font. We also noted how some parishioners having seen something they really liked elsewhere, wanted it copied for their own church, as in the case of Richard Wekys a butcher from St Mary Magdalen’s church and the painting of an image of Our Lady in the Lady Chapel there.

Having examined such personal interactions with the saints, we moved on to consider the role of parish fraternities. Of these, I looked in more detail at that of the Jesus Mass because this was also an important innovative devotion which seems to have come early to Kent from mainland Europe. Initially established at Sandwich and at Lydd by the mid-1460s, it was also at Holy Cross church in Canterbury before 1470 and thereafter another 6 churches in the city had such fraternities. Yet Holy Cross seems to have retained its premier position having fraternity wardens and its own priest. One of those who supported this devotion was John Blake a parishioner there for he left a house to his wife with the proviso that she was to use 6d from the rent annually to help sustain the Jesus Mass at Holy Cross and to have John’s name in the bede roll so that he would be remembered and prayed for like other brothers and sisters there.

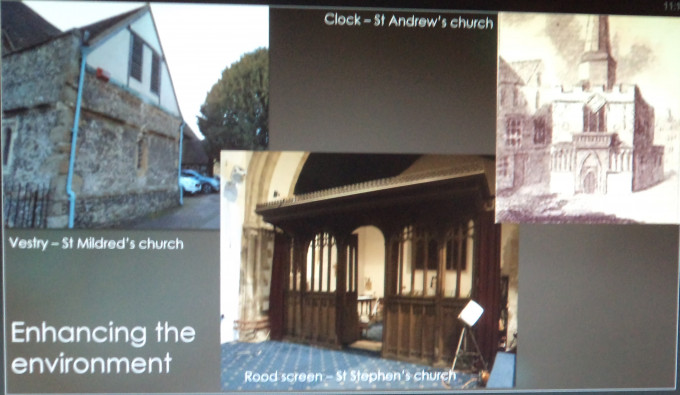

Next came the ways Canterbury parishioners sought to enhance the physical and spiritual environment of their church. Having started at the west end, we found that at least 6 churches had bequests towards aspects of the belfry from repairs to possible rebuilding. The nave, too, was well supported at even more churches and while some testators bequeathed cash for general repairs, others were more precise, such as Thomas Prowde at St Aphage’s church who gave for the fabric of a column which was to have a niche for an image, and Edmund Swanne who left 40d towards making a new window at the church of St Mary Bredin. The rood screen and loft were of special concern in the late 15th and early 16th centuries at many of the city’s parish churches, and the new vestry at St Mildred’s church can be dated from James Aylonde’s will. Other aspects mentioned by testators across the city include pews, choir stalls, organs, vestments, a laten candlestick for the pulpit at St Paul’s church, the clock on the steeple at St Andrew’s church and the Easter Sepulchre at St Mildred’s church.

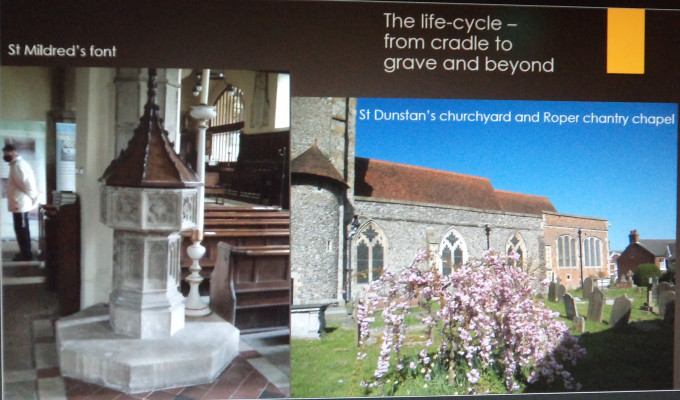

The last part of this section considered life as a pilgrimage by charting from cradle to grave and beyond, especially how testators sought to help their fellow parishioners at these crucial points in the life cycle. For example, Jone Crisseld gave a mazer to the vicar which was to be lent to poor child wives and poor folk that married in St Paul’s church for their marriage day. Moving on, Dorothy Lawrence of St Andrew’s church bequeathed 2 sheets and 2 pillows to poor women about to give birth in the parish, these items to remain with the churchwardens for as long as they lasted. And again, Christine Beneyt bequeathed 3 cushions and similar items for use by women on their purification day in St Mildred’s church. Equally, we explored the increasing popularity of the desire for the 3 ‘funeral’ dates of burial, the month’s mind and the obit or 12 month’s mind as ways to commemorate the deceased and the variety of ways sought by testators. For most this included charity for the poor, such as Thomas Ingram at St Margaret’s church who wanted at his burial 13 gowns and 13 caps to be given to 13 poor people to sing for his soul. For those able to afford far more extensive acts of commemoration, there were temporary chantries and for the wealthy the chance to establish a perpetual chantry, the Roper chantry chapel at St Dunstan’s church, Hamo Doge’s chantry at St Paul’s and the Atwood chantry at St Mildred’s.

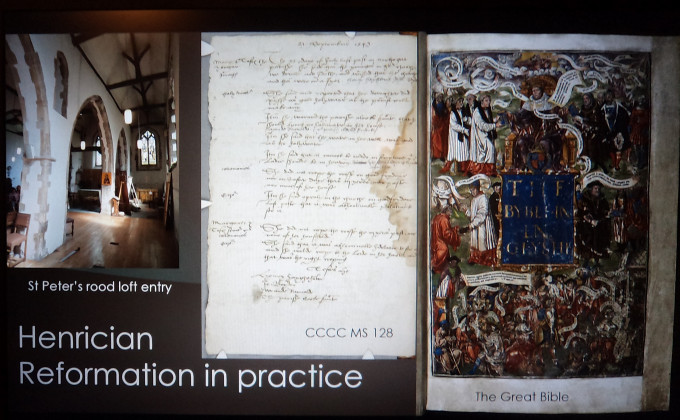

This brought me to my final section and looking at the parish and people during the Henrician Reformation, especially the snapshot provided by the depositions collected by Archbishop Cranmer as part of the response to the Prebendaries’ Plot. Apart from anything else, these suggest a few parishes had become battlegrounds between those who wished to keep traditional worship and those who wanted to push towards the reformist position. Of course, the destruction of images featured here, but perhaps even more interesting is the reading of the Bible in English, especially when read to others and most particularly to women.

Having used this as a way of concluding, the audience asked a number of very interesting questions and the next time I’ll be in St Paul’s church it will be for the conference on the 28th September.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1843

1843