Stop Press! The FREE tickets for the Medway History Showcase on Saturday 21 October are available to book at: Royal Engineers Museum Tickets, Products, Membership Plans – Buy Online (digitickets.co.uk) or go to the Royal Engineers, Gillingham website and Medway History Showcase – Royal Engineers Museum (re-museum.co.uk) and see the ‘BOOK TICKETS’ tab on the right-hand side. We hope to see you there for a great day showcasing the history of north Kent.

Now for two events coming up very, very shortly, tomorrow evening the Centre is working with the Friends of Canterbury Archaeological Trust for the October lecture, which will be given on Thursday 5 October by Dr Lindsey Büster (Archaeology at CCCU)on ‘Commios: Iron Age Britons and their continental neighbours’ at 7pm in Newton Ng07, Canterbury Christ Church campus. This lecture is open to all and is free to students, while for visitors and Friends the usual donations are asked for towards the work of CAT.

Then on Friday the Canterbury Society will be holding its annual Heritage Lecture at the University of Kent in the Templeman Library Lecture Theatre at 6pm. The Lecture will be given by Henrietta Billings, director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage and her title is ‘Heritage and the climate crisis: how protecting the past can save the future’. The lecture is free and there is no need to book.

There is also an opportunity during October and beyond to see the Maison Dieu Archaeology Exhibition at the Dover Museum. Keith Parfitt and the volunteer team of History Diggers found some fascinating objects, including pieces of late 13th century medieval glass. The free exhibition is on until the end of 2023: https://www.maisondieudover.org.uk/events/recent-archaeological-discoveries-at-dovers-maison-dieu-exhibition

On matters relating to CKHH, Dr Diane Heath is delighted that the Rochester Bestiary exhibition at Rochester Cathedral is going extremely well – see last week’s blog, the second instalment of the NLHF money is in place and she has also applied elsewhere for further funds to ensure this great project of working with SEND families using medieval animals can continue. So that we can showcase the projects of the Centre, Dr Claire Bartram has been liaising with a member of the CCCU web team concerning a new website for CKHH, this is an exciting development and hopefully will start to come to fruition in the next couple of months. One of the reasons is that we want to get the details of the Medieval Canterbury Weekend 2024 up on the new website well before Christmas. The schedule is coming on nicely, and I’ll preview more of our speakers next week.

However, for this week I thought I would delve into the late medieval Canterbury wills from the 1470s, when these activities were seemingly at their height, just to highlight that urban infrastructure and civic reputation were as much issues then as they are now bearing in mind today’s announcements. But before I get to the wills, I just thought I would mention the city’s petition to parliament in the same decade to be able to raise money to pave certain key streets of Canterbury because ‘the same Cite is oone of of the eldest Citees of this Reame and therin is the principall See of the spirituell estate of the same Reame And whiche Cite also is moste in sight of alle Straungers of the parties beyond the Se resorting into this seid Reame and departing oute of the same And because of the glorious Seintes that there lye shryned is gretely named thorought Cristendome vnto which Cite also is grete Repeyr of moche of the people of this Reame aswell of estates as other in wey of pilgrimage to visite the seid Seyntes And it is so that the same Cite is often tymes full fowle noyous and vneasy aswell to alle the inhabitauntes of the same as to alle other persones resorting thereunto wherof often tymes is spoken moch disworship in diuerse places aswell beyond the Seas on this side of the Se ..’- so in some ways things don’t change!

Yet, it is worth noting, and here I’m just going to pick out a few examples, the leading Canterbury citizens also saw such care for the well being of their city as a personal duty, albeit such ‘good works’ were viewed as charitable acts in line with the Seven Corporal Works of Mercy. Keeping initially with paving, and it is worth bearing in mind there were a number of gravel pits beyond the city walls in the wards of Worthgate and Ridingate, among such benefactors was Roger Rydle. Having served in civic office, he was presumably keenly aware of the situation when he made his will a couple of years before his successors’ petition, leaving 66s 8d towards paving the Bulstake (today’s Buttermarket) on condition others similarly donated funds for the work. Not that he was the first to see the communal value of improving the streets and the marketplace because William Benet, a few years earlier, had bequeathed £10 towards repairing the shambles used by ‘strange’ (from outside Canterbury) butchers to ‘occupie euery market day’ and for paving the street from St Andrew’s church to the pillory (another market place) ‘that the peply may go the clener therto’.

At about the same time, others were looking beyond central Canterbury to the highways leading into the city. For example, William Bigge, another member of the civic authorities expected his executors to provide 33s 4d from his estate towards repairing ‘foul ways at the spytel hill’, perhaps at Harbledown and St Nicholas’s hospital on the approach from London towards the Westgate. If this is the right hospital, he was not the first to repair this roadway because in 1463 William Clerk, a brewer, had bequeathed 40s towards repairing the road near the parish church at Harbledown. Moreover, he was similarly keen to see repairs to the road leading out on the opposite side of Canterbury because he left a further 40s for the stretch between the ‘Fowrehedd’ cross and Littlebourne.

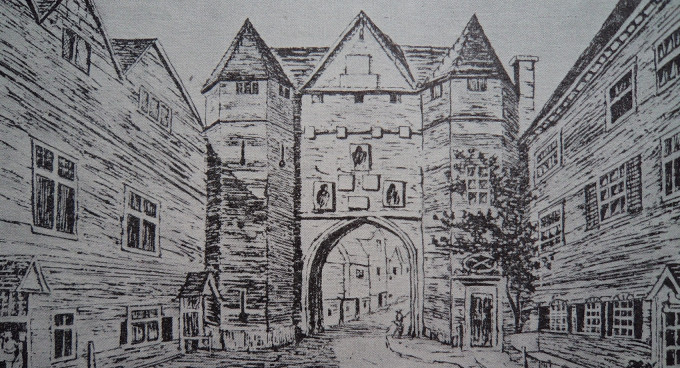

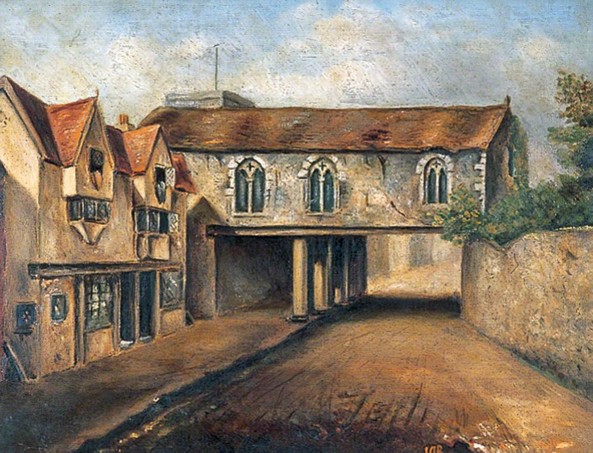

Nor were roads the only structures seen as requiring improvement and while William Benet was alone in wanting his executors to buy 300 feet of dressed Folkstone stone to make a wharf at the king’s mill, for which they were given £5, concern for the state of some of the city’s gates was more widespread. Of course, the Westgate having been rebuilt around 1380 was in a good state, but others were not. In particular, there was a concerted effort to rebuild Newingate or St George’s gate. Amongst those who contributed through his will was William Bigge (1470) who left the large sum of £10 which was to be paid ‘as the work progresses’.

His lead was followed shortly after by Roger Rydle who too stipulated similar conditions on his bequest of 66s 8d towards the rebuilding of this gate. Such bequests were presumably very welcome for the mayor and his brethren as a means to defray some of the costs, not least because the stone for the new gate was specially quarried near Maidstone and then brought from that town by boat as far as Whitstable before being brought on the last stage of the journey by cart. Nor was this the only gate receiving attention at this time because Burgate, too, was the beneficiary of Laurence Soper’s largesse, albeit only from the reversionary bequest if his son pre-deceased his widow.

A couple of years later, in 1475, John Frennyngham, yet another senior civic officer, mentioned such charitable works among his bequests including £20 which was to go towards repairing St Michael’s church, but also potentially the gate (Burgate) or yet more towards paving the Bulstake. Interestingly, he left an additional £13 6s 8d to road repairs around Canterbury and a further £6 13s 4d to the bridge at Fordwich.

Such bequests are interesting and while they can only provide part of the picture, they do throw up fascinating parallels, I think, as well as providing insights into the mindset of those living in the city more than 500 years ago.

Centre for Kent History and Heritage

Centre for Kent History and Heritage Sheila Sweetinburgh

Sheila Sweetinburgh 1370

1370